Scandalissimo! Puccini's sex life exposed

The private life of Giacomo Puccini was famously as colourful as his operas, but only now has the truth emerged about the scandal that almost undid him. It's an extraordinary tale of infidelity, jealousy and vengeance that continues to haunt the lives of his descendants to this day

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

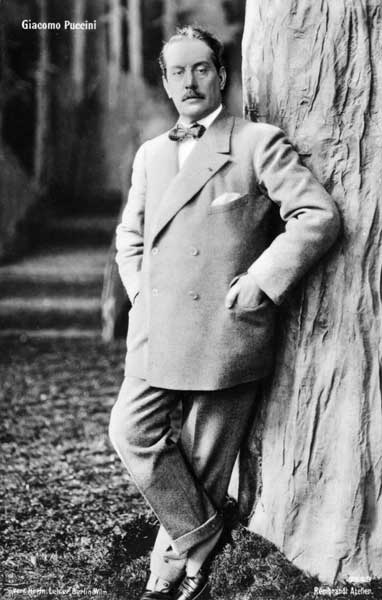

Your support makes all the difference.This year, the many celebrations marking the 150th anniversary of Puccini's birth are set to include the unveiling of a new al fresco opera house on the shores of the lake where many of his masterpieces were composed. Giacomo Puccini was the most commercially successful opera composer there has ever been. At his death in 1924 he was worth well over £130m by today's standards.

Much of this wealth came from the wonder years (1895-1904) when the Tuscan maestro turned out in rapid succession three of the most widely performed operas in the world, La Bohème, Tosca and Madama Butterfly, while living in idyllic surroundings in Torre del Lago on the shores of Lake Massaciuccoli. Then he seemed to run out of steam, not finishing his next work, La Fanciulla del West, until 1910. While accomplished, La Fanciulla isn't in the same league as Bohème, Tosca and Butterfly. So what went wrong?

For years it was assumed that the suicide of a maid working in the Puccini household may have had a lot to do with it. The story is well-documented. On 23 January 1909, Doria Manfredi committed suicide by taking three tablets of corrosive sublimate. It took three days for her to die from what today we would call mercury poisoning. Elvira Bonturi, the composer's 39-year-old wife, was blamed for her death, for she had hounded Doria and publicly accused her of having an affair with Puccini. When the local court ordered an autopsy, it was found that Doria was a virgin and Elvira was sued for slander. She was sentenced to five months and five days and only escaped prison when the composer offered 12,000 lire compensation to the Manfredi family. Subsequently the couple were estranged for some months, but this tragedy hardly accounts for the seven years it took Puccini to complete La Fanciulla. Besides, Elvira's persecution of Doria only began in the October of 1908. The dates simply do not match up.

Recently, fresh light has been shed on what went on in Villa Puccini 100 years ago. Giacomo Puccini had made his home in a fishing village called Torre del Lago. Here, surrounded by his common-law wife, his stepdaughter and son, he wrote music, went out in fast cars, or took his speedboat out on the lake. Or as he himself put it: "I am a mighty hunter of wild fowl, operatic librettos and attractive women."

It was Puccini's pursuit of women that created the great crisis in his life. This is a tale of infidelity, jealousy, vengeance and despair. It goes a long way towards explaining the composer's fallow period. Its repercussions are still being felt on the lakeside today.

The story begins not with Doria's suicide, but eight years earlier when Puccini was working on Madama Butterfly. It was not uncommon for the maestro to fall in love with other women when composing. He called these amourettes his "little gardens". In 1900, while working on Butterfly, Puccini fell for a young girl he met in Turin. He nicknamed her "Corinna" and was so obsessed with her that Elvira, in despair, contemplated leaving him .

Puccini and Elvira Bonturi were not married at the time. She was the wife of an old schoolfriend of his. The couple had met in 1884 when Puccini was hired to give Elvira piano lessons. They soon began an affair. In 1886, amid much scandal, Elvira had left her husband for Puccini, bringing her six-year-old daughter Fosca with her to Torre del Lago. In due course Elvira bore Puccini a son, Antonio, but the couple were unable to marry and legitimise the boy because divorce was not possible in Italy at that time. The situation may well have suited the composer, who claimed he enjoyed falling in love and certainly enjoyed teasing Elvira about his "little gardens". This time, however, the infatuation got out of control. There are suggestions that Puccini had proposed marriage to his Corinna.

However, on 25 February 1903, fate took a strange turn. On that night Puccini suffered the first-ever motorcar accident to receive widespread press coverage in Italy. Near Lucca, his chauffeur plunged off the road. The composer was found pinned underneath the car, almost asphyxiated by petrol fumes and with his right leg broken. He needed someone at home to care for him. And the very next day, by another strange act of fate, Elvira became a widow. Her husband Narciso died, leaving no obstacle to Puccini marrying his companion of 17 years.

Puccini's publisher and mentor, Giulio Ricordi, tried to convince the bedridden composer to give up Corinna and do the decent thing by Elvira. Goaded by Ricordi and pressed by his ever-attentive sisters, Puccini hired a private detective, who discovered that the Turinese girl had duped him. She was not the innocent she pretended to be. Not only was she having relationships with other men, there was ' a strong possibility money was changing hands. Puccini broke definitively with her in a note burning with shame and anger: "What an abyss of depravity and prostitution! You are a shit, and with this I leave you to your future."

Stung, Corinna wrote to him threatening legal action and to go public over the affair. Puccini panicked. We know this from a note that Elvira subsequently wrote to him.

"For that business [the alleged breach of promise] you could have gone to gaol... I still remember well how, when the famous letter [from Corinna] arrived, you became pusillanimous at the thought of a sentence and talked about fleeing to Switzerland."

According to recent research by musicologist Dieter Schickling and novelist Helmut Krausser, the situation was rescued when Corinna's father was convicted for importuning and exposing himself to an underage girl. Any accusations made by the daughter of such a family would have enjoyed little credibility in the Italian legal system. Puccini was saved but humiliated. Among Schickling and Krausser's discoveries was the fact that the Corinna correspondence was not in any Puccini archive but in the possession of the family of Elvira Bonturi's sister.

"Perhaps Elvira passed the documents to her sister for safe-keeping," says Puccini producer and scholar Vivien Hewitt, "so that she would always be able to remind him about them if he strayed in the future."

The following year, on 3 January 1904, a week after finishing Butterfly and as soon as the legal 10 months of widowhood were up, Puccini married his Elvira. It could hardly be called a good start to a marriage.

"Puccini's personal life and his creativity were always intertwined," says Hewitt. "His heartbreak over Corinna was probably instrumental in generating his most powerfully tragic music in the form of the last act of Madama Butterfly."

After 'Butterfly', the humiliated composer did not produce another opera for six years. When that opera was finally completed, it depicted a new kind of Puccini heroine: not a victim like Mimi or Butterfly, nor a jealous, destructive creature like Tosca, but a tough, capable woman, Minnie, who runs a saloon in a California mining camp.

Many people have asked where Puccini found his new muse. One of those intrigued by this question was Italian film director Paolo Benvenuti, whose film La Ragazza di Lago (The Girl of the Lake), premieres at the Venice Film Festival this August.

"Six years ago I started an in-depth research project centred on the suicide of Doria Manfredi. I soon noticed that while writing an opera, Puccini tended to fall in love with a real-life person similar to his protagonist. I could see no similarity between Doria and the heroine of La Fanciulla del West, but my research team revealed there was another woman in Torre del Lago who bore a striking similarity to the independent, gun-toting saloon owner Minnie. That woman was Doria's cousin, Giulia Manfredi."

Like Minnie, Giulia worked in a hostelry frequented by hunters and local farmers. This was the Chalet Emilio, named after her father, Emilio Manfredi. It still sits on the edge of Lake Massaciuccoli today, opposite Villa Puccini.

"She was independent and commanding but at the same time humble and affectionate with locals and strangers alike," says Benvenuti.

Gossip in Torre del Lago suggested that the composer had had an affair with Giulia, but Benvenuti had no evidence. "Then in October 2006 my research co-ordinator overheard a seaside pizza-parlour owner in Lido Di Camaiore saying that the illegitimate son of Giacomo Puccini and Giulia Manfredi always used to eat in his restaurant."

Believing that he was on to something remarkable, Benvenuti followed up the lead, tracing the Manfredi family to a modest house in Cisanello near Pisa. "The woman who answered the door was Nadia, a simple housewife who had always worked as a hairdresser. She was the daughter of Antonio Manfredi, a hotel night porter who had lived in Pisa almost all his life."

One thing Benvenuti noticed immediately: Nadia Manfredi has Giacomo Puccini's hooded eyelids.

"Nadia is a sweet, rather shy person," says Benvenuti. "She has suffered a lot from her father's sense of abandonment and his appalling doubts about his identity."

In January 2007, Nadia showed Benvenuti a dusty suitcase of her father's that had been kept in the cellar for years. Inside, the director found approximately 40 letters and various documents that revealed the truth behind the suicide of her great-aunt Doria. Most important among these was a handwritten, undated memorandum Puccini had written on two sheets of headed notepaper from a Milan hotel where he was staying. These notes reconstructed the sequence of events that led up to Doria's death.

The story that was revealed is much more complex than Elvira Bonturi's jealous persecution of an innocent domestic servant. The tragedy begins around the end of September 1908, when Puccini sent word that he was returning to Torre del Lago. By this time he had found his new "little garden" in the feisty Giulia Manfredi and was already working on Fanciulla. Puccini asked that Doria open up the house ahead of his return. "By accident," says Benvenuti, "Doria discovered Puccini's stepdaughter, Fosca, in flagrante with the librettist of Fanciulla, Guelfo Civinini, in Villa Puccini." Fosca was 28 at the time and married to the impresario Salvatore Leonardi. "Fosca was afraid that Doria would tell all so she decided to discredit Doria and accused the girl of having an affair with her stepfather. Puccini's wife Elvira sacked Doria."

Distressed, Doria wrote to Puccini, saying that Fosca had plotted against her to cover her own immoral behaviour. Puccini secretly met with Doria and reassured the girl that he would try to sort matters. We do not know if he did anything at all, but we do know that when news of Doria's accusation reached Elvira, she was furious. "She was convinced Doria was adding insult to injury," says Benvenuti. "Elvira was certainly spying on her husband at the time and one night she saw him in a compromising situation with another woman whom she now assumed to be Doria.

On 1 January 1909, Elvira accosted Doria and her cousin Giulia and called Doria a "gossip and a filthy creature". On 19 January she insulted Doria in front of the Villa Puccini before witnesses, calling her a "whore" and a "tart" and subsequently told the onlookers that Doria was a "tramp who ran after my husband" and that "sooner or later I will drown her in the lake". On 23 January she accused Giulia Manfredi of being a go-between for Puccini and Doria, and told her that Doria would never set foot in Torre del Lago again.

"Doria was entirely innocent," says Benvenuti. "But she could not defend herself without betraying both her cousin and the maestro, whom she revered and adored."

After Doria's drawn-out and painful suicide, the local court stepped in and ordered an autopsy, which revealed the girl to be a virgin; Doria's family took Elvira to court. She was convicted of defamation, slander and menaces towards Doria Manfredi on three separate occasions.

The impact on the Puccini family was huge. "Not only was there was a separation between Puccini and his wife," says Benvenuti, "but Fosca's husband, the impresario Leonardi, got wind of the truth and blackmailed her. Eventually Fosca appealed to her mother for financial help and confessed the truth [about her relationship with Guelfo Civinini and Doria's discovery that day in autumn 1908]. By this time, Elvira's finances were drained too and in the end she had to admit the truth to Giacomo and beg for help. He took her back, paying the Manfredi family to drop their legal action and Leonardi for his silence." Elvira avoided prison and as the repercussions died down, Puccini recovered something of his creativity.

But in researching his film on the two Manfredi girls, Benvenuti found he had uncovered much more than he expected. "Puccini's relationship with Giulia lasted until his own demise. Many years later, in June 1923, Giulia had a son and christened him with Puccini's grandfather's name, Antonio. The boy was farmed out to a nurse in Pisa and a contract was drawn up with her for the then-massive sum of 1,000 lire a month. Significantly for those who are sceptical that Puccini was the father of Antonio Manfredi, Benvenuti points out that the maintenance money stopped abruptly in December 1924, just days after the composer's death in Brussels.

Young Antonio was brought up away from Torre del Lago in the city of Pisa. Says Benvenuti: "Antonio Manfredi died in poverty, aged 65, in 1988. Like Giacomo and Elvira's son (also called Antonio Puccini), he died of a tumour. He bore a very striking resemblance to Puccini, as you can see from his photograph. In fact there is a resemblance that descends through the generations in the photographs of his daughter, Nadia Manfredi, his granddaughter, Giada, and his great-grandson, Giacomo Manfredi. Giacomo, now 10, is the spitting image of the young Puccini."

Emboldened by her conversations with Paolo Benvenuti, on 20 February this year Nadia Manfredi went before a court in Milan requesting a comparison between the composer's DNA and that of Antonio Manfredi. "I wish to establish whether my father was Puccini's son," she explained. "I am interested in the moral satisfaction of knowing the truth, one way or the other, so that I can put my ghosts to rest."

This move has been opposed by Simonetta Puccini, who owns Villa Puccini. In 1980, as Simonetta Giurumello, she went before Italy's highest civil tribunal, the Court of Cassation, to prove she was an illegitimate daughter of the composer's legitimate son, Antonio. Antonio Puccini had died without an heir in 1946. Thirty-four years later, Simonetta Giurumello was able to get herself legally recognised as his daughter. At that point she changed her name to Puccini, obtained a decree from Milan freezing all existing Puccini assets, and took possession of the villa in Torre del Lago.

Nadia claims she is not motivated by the Puccini fortune. "I want justice for my father because he died in complete poverty, like a beggar. My father spent his entire life not knowing who his father was. I hope to give a name to the father of my father."

Lawyers for Simonetta argue that in Italy, while the first generation have forever to prove paternity, a statute of limitation of just two years applies to subsequent descendants, such as grandchildren. Nadia's lawyers are requesting that the limitation should run for two years after finding evidence, not after the death of Giacomo Puccini.

It is significant that while Puccini's creative recovery began with La Fanciulla del West, he only regained the form that he had displayed in Bohème, Tosca and Butterfly with Turandot, the opera he was still writing at the time of his death. Interestingly, the composer hit a new musical wall in 1922 while telling the story of the vengeful, man-hating Chinese empress. It was only when he instructed his librettists to create the character of a poor servant-girl, Liu, who commits suicide rather than betray the opera's hero, that he was able to continue. Puccini died with the last act of Turandot incomplete, haemorrhaging in the aftermath of drastic throat surgery. According to the conductor Arturo Toscanini, the maestro laid down his pen after the suicide of Liu. Doria Manfredi was to haunt Puccini for the rest of his life, while her cousin was left holding the baby.

The 54th Annual Puccini Festival runs from Friday to 5 September in the village of Torre del Lago Puccini, Italy.

Adrian Mourby is the recipient of the 2007 Puccini Award for Journalism. An extended version of this piece was first published in 'Opera Now' magazine

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments