Roxy Music, Suede, Blur: Why do partnerships fizzle out?

With the re-release of Roxy Music's debut album on its 45th birthday, it's time to reevaluate the chemistry between Bryan Ferry and Brian Eno, and to look at other partnerships that fell by the wayside

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

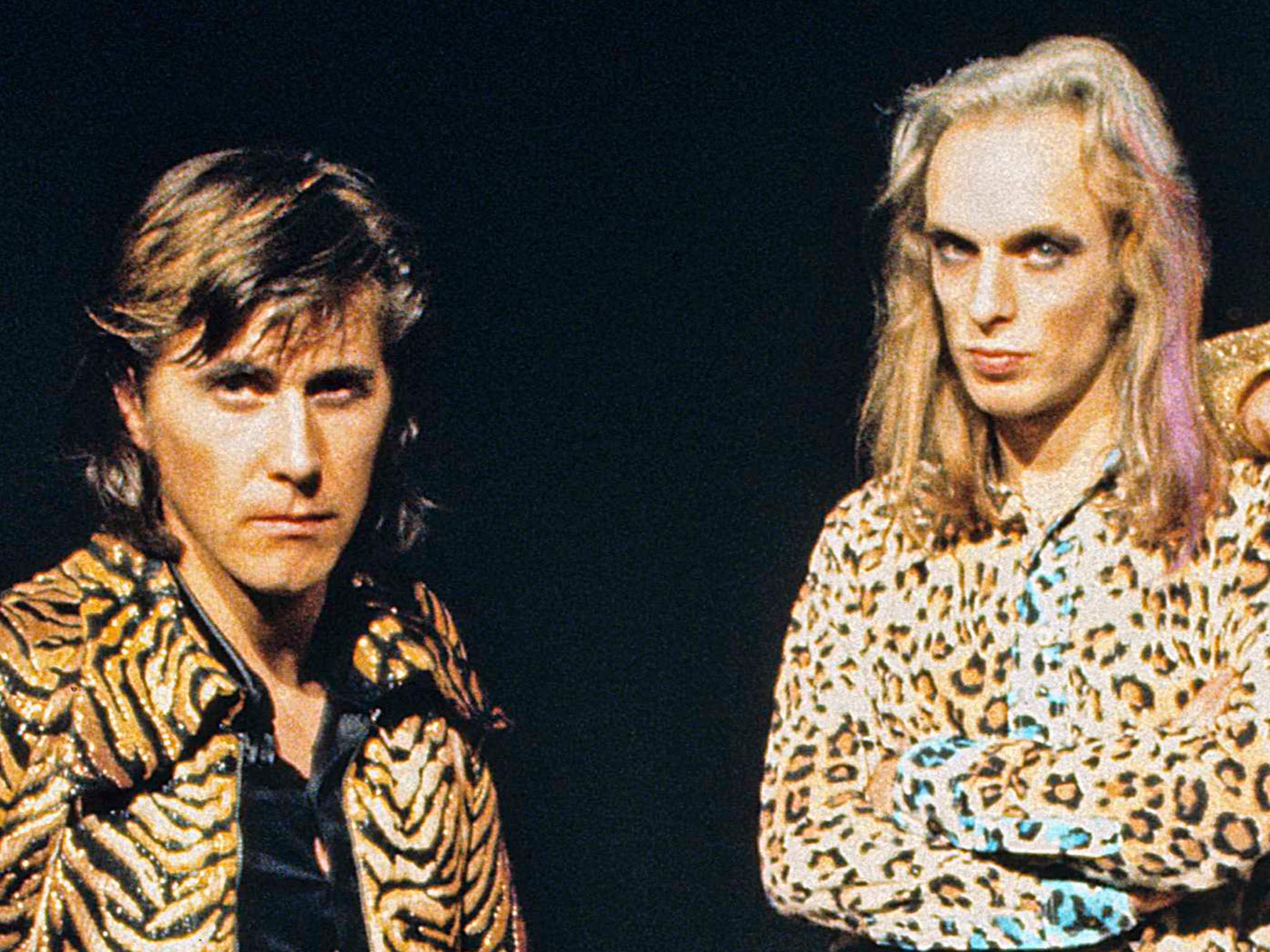

Your support makes all the difference.These days, Roxy Music are pretty much synonymous with the louche figure of Bryan Ferry, though while the often tuxedoed frontman was always the group’s driving force, the re-release of their debut, eponymous album tells a more nuanced story.

A box set of Roxy Music, one of the group’s best, reminds us of the importance of creating the right chemistry within a band and maintaining that mix despite feuds, fall-outs and rivalries, a conundrum that continues to baffle musicians today.

As the classic Roxy line-up coalesced in 1971-2, Ferry was keen that the outfit should reflect both his art-school progressive tendency and nostalgia for the glamour of bygone ages, particularly 1950s teen scenes and Hollywood’s 1940s golden age. Yet the former ceramics teacher was not yet the martinet that would in later years take full grasp of the creative reins. Instead, members were free to express themselves, none more so than synth manipulator Brian Eno.

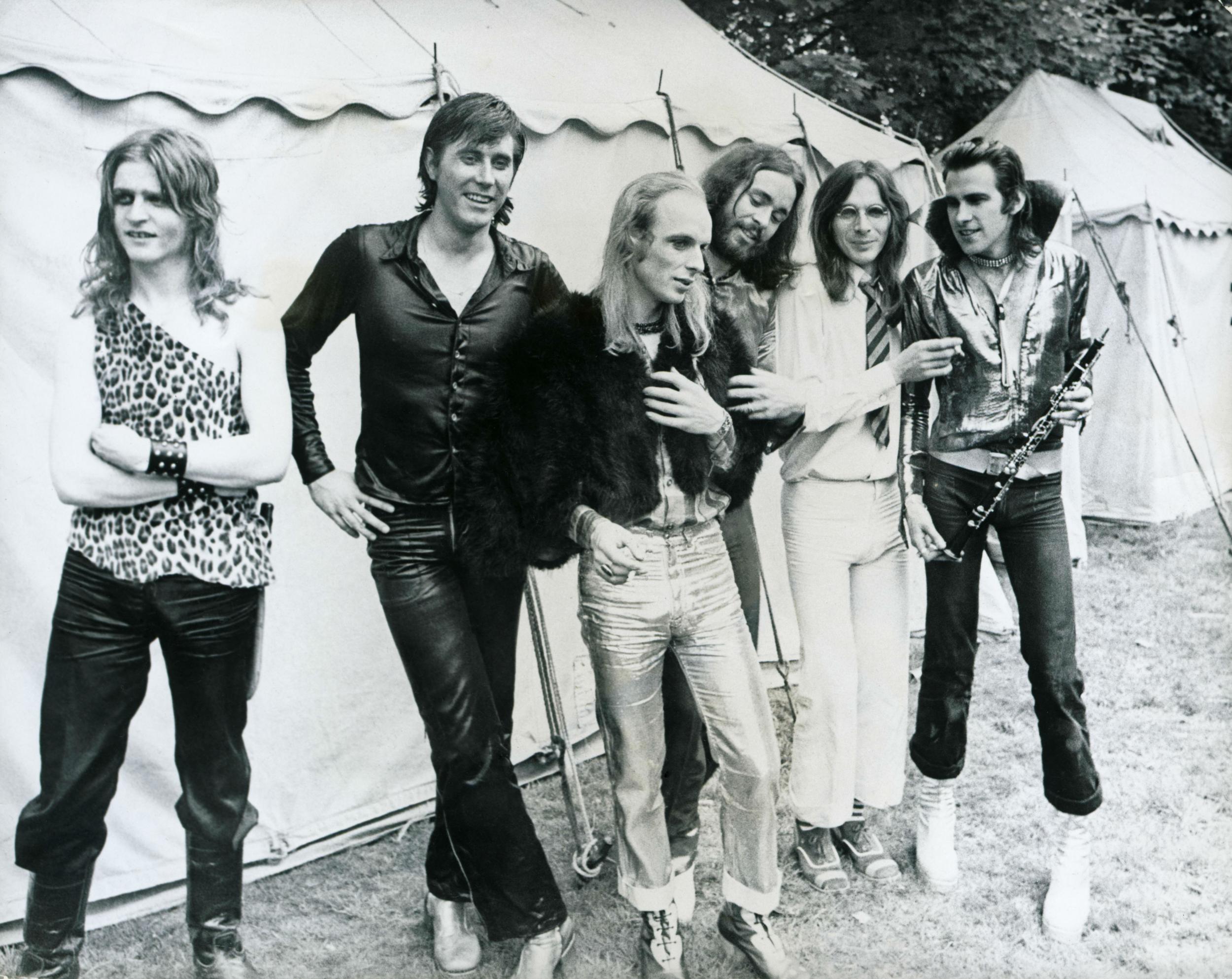

Experimenting with sax/oboist Andy Mackay’s made-in-Putney VCS3, Eno developed the modern in Roxy’s post-modern mix of influences – pop, rock, prog and old-school crooning – yet was just one competing voice as Roxy evolved through their first months as a band. The early demo tape, now remastered, that Ferry offered to labels and management companies featured the more classically blues-based guitar of Roger Bunn before final arrival Phil Manzanera (having failed an earlier audition) brought a zingier, more unruly attack.

Also vital as a counterpoint to the arty flourishes of the rest of the line-up was the sturdy drumming of Paul Thompson, a Geordie like Ferry, who first met Roxy straight from a building site, even though he had previously backed veteran rock’n’roller Billy Fury. Shades here of a sticksman apart from other group members, whether the non-grammar schooled Ringo Starr in The Beatles or former child actor Phil Collins in Genesis.

Yet it was Eno who would provide the biggest challenge to the band leader’s authority. In a group happy to style themselves in glam trappings, the befeathered Eno stood out and soon began to draw attention away from Ferry, especially when he halted the practice at early gigs of performing at the sound desk rather than on stage. By the end of 1972, the synth player was a pin-up for the more cerebral tendency of glam rock, who also gave great quote. In his masterly history, Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and its Legacy, Simon Reynolds picks Eno’s bitchy comment: “I certainly don’t want to find myself sliding down the Slade/T Rex corridor of horror.”

Roxy would achieve their creative apex the next year with their brilliant follow-up album For Your Pleasure, notable for greater input from Eno that provided disquiet to its darker, richer content. Sensing a rival, Ferry ejected him from the group, four months after the album’s release. His band would achieve greater commercial success, but with less critical acclaim, having made clear Roxy was a vehicle for his ideas alone.

Eno, though, may not have lasted much longer, given his distaste for “Slade/T Rex” pop fame and desire to pursue more experimental avenues. It is ironic that Velvet Underground were a massive influence on most members of Roxy, with the New York-based group faced with a similar situation. Lou Reed had cut his teeth penning pop songs for cash-in purposes and now wanted to tell tales of Manhattan street life, while bandmate John Cale came from a classical, experimental background. Their output together over two albums gained only a cult following at the time, causing Reed to force the Welshman out in 1968 while aiming for a more accessible sound. Changing the line-up failed to bring a change in fortune for the Velvets, with Reed himself departing two frustrating years later.

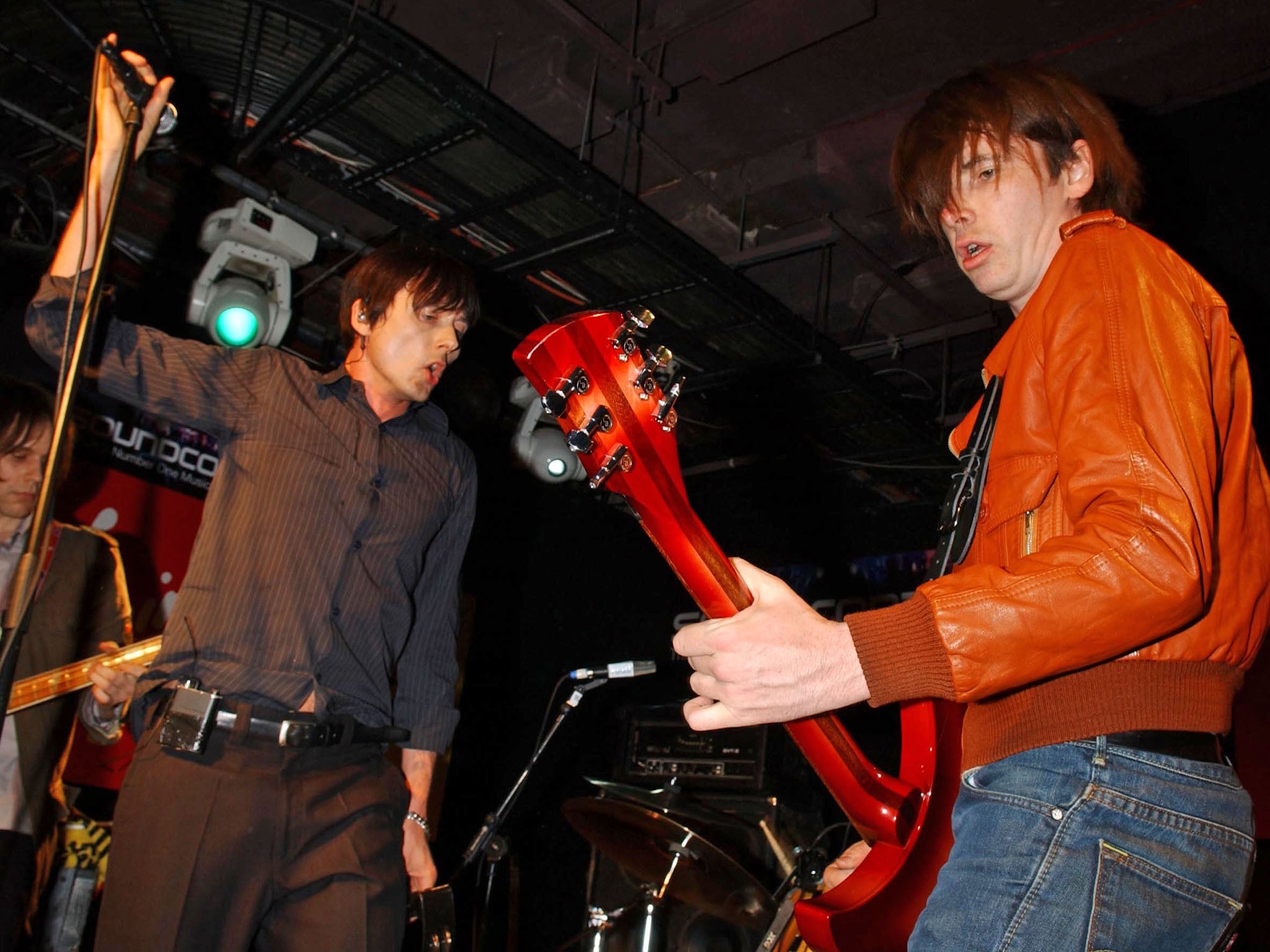

Roxy’s defiantly Euro- or even Anglocentric aesthetic, heard most clearly in Ferry’s mannered vocals, was a clear antecedent in the early Nineties for Suede, a group whose success hinged on the polymorphous charisma of singer Brett Anderson and Bernard Butler’s take on wild glam guitar. In 1993, the four-piece were untouchable, their debut, eponymous album topping the UK charts, but divisions surfaced while recording epic single “Stay Together”, a chart hit but an excursion that saw relations sour between Butler and the rest of the band, though especially Anderson.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

While they had kickstarted Britpop, they felt appalled by its laddish evolution, a challenge that perhaps exacerbated existing all-too-familiar tensions. The two began sparring in interviews, Butler accusing Anderson of rock posing, while the latter criticised the former’s pedestrian musicianship. In the end, having demanded the sacking of producer Ed Buller, Butler found himself locked out of sessions for their second effort, Dog Man Star. While that hotly anticipated album was itself lauded and proved the group could prosper without Butler, Suede struggled to maintain momentum in later years.

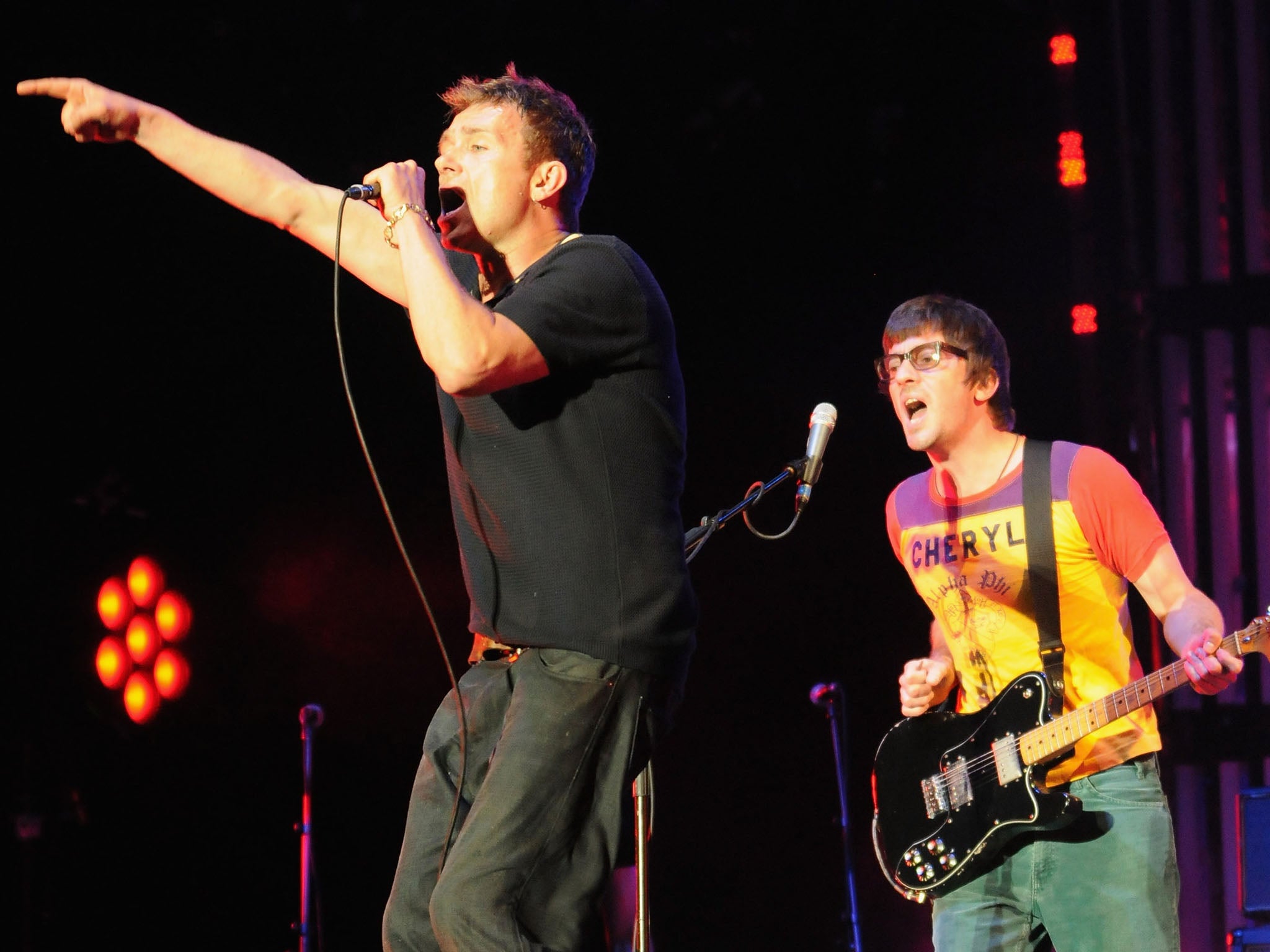

A similar dichotomy could be seen in the next decade within Britpop rivals Blur, with Damon Albarn’s bold ambition and pop tastes rubbing up against Graham Coxon’s more lo-fi, indie aesthetic. The former wanted to hijack the pop mainstream, while the guitarist preferred a more low-key palette, a fusion that kept the band vital and interesting post-Britpop, though the strain told on Coxon, who having struggled with drink issues was asked to leave during 2002 sessions for Think Tank.

Sometimes it is not creative differences or divergent ambitions that cause tensions, but varying abilities to cope with the pressures of being in a successful band, whether falling prey to available temptations or lacking the stamina to cope with a touring lifestyle. In that respect, Coxon fell in the same boat as one of his inspirations, Syd Barrett, ejected from Pink Floyd in 1968 after one trip too many, or The Clash’s drummer Topper Headon, fired while falling to heroin addiction.

Coxon has since returned to the fold, the creative differences between him and his musical foil now evinced in side projects – compare the cartoon behemoth of Gorillaz with Coxon’s more homespun soundtrack to streaming hit “The End of the F***ing World”. It is difficult to accomplish when a band is struggling or even on the up, but if each member has space to express themselves, that all-important chemistry stays all the longer.

‘Roxy Music’ by Roxy Music is out on 2 February via UMC in formats including a four-disc box set

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments