Record Store Day: Remembering an era when buying and selling discs were labours of love

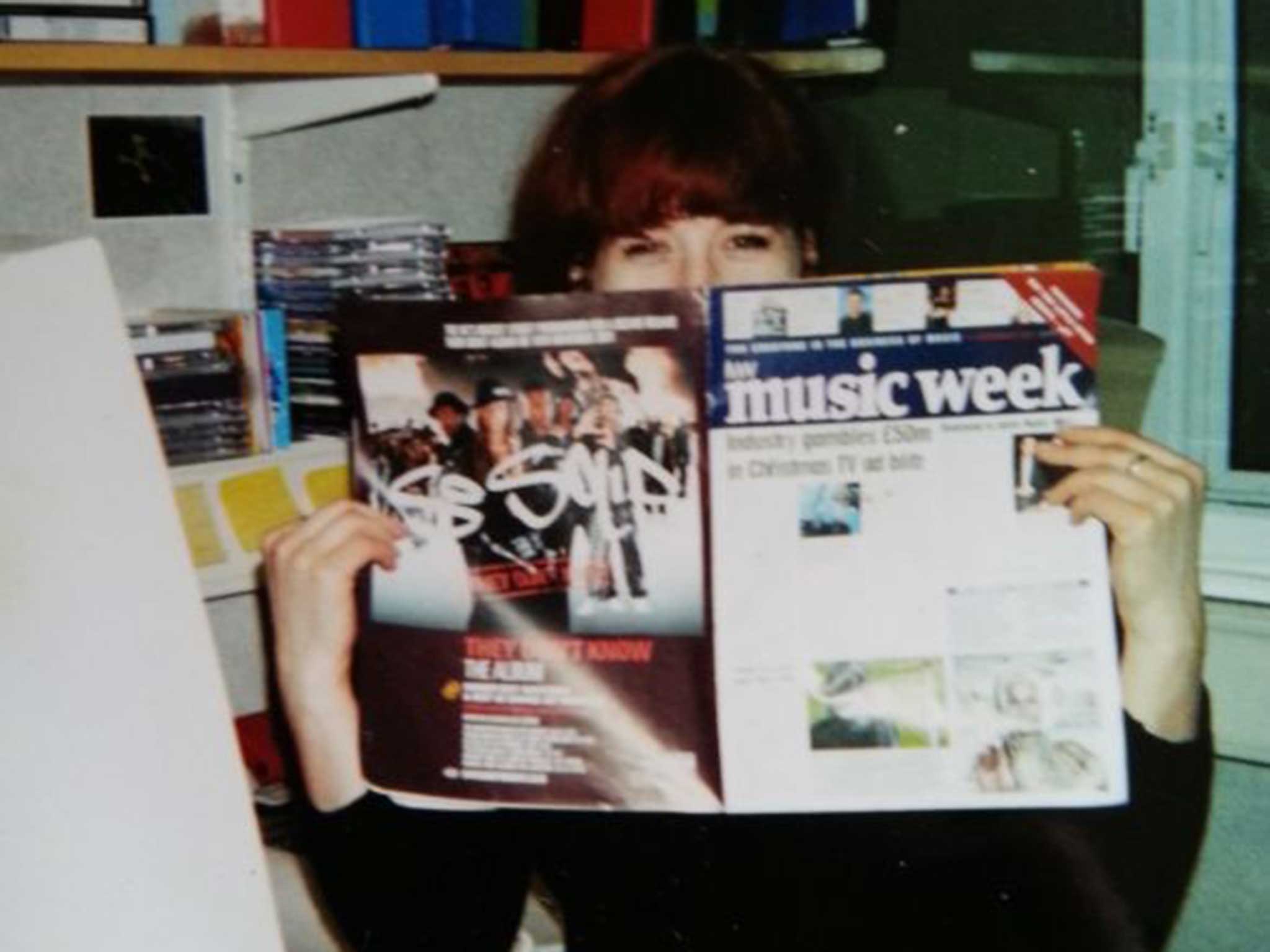

For Lois Pryce, working in a record shop was a dream job - until the bean counters ruined it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.My obsession with vinyl began, aged 13, in 1986, when I was waiting for a bus home from my granny's house and strayed into the decidedly uncool John Menzies in Bath bus station. I purchased my first LP, a budget offering of Gene Vincent's greatest hits, and my life changed forever. Rock'n'roll became my religion and I worshipped every Saturday morning at Tony's Records, Bristol's finest and much-missed independent record shop. My weekly pocket money and dog-walking wages fed my habit, but there was another benefit to my newfound passion: at last I had an answer for the grown-ups when they asked what I wanted to do when I grew up – work in a record shop, of course.

It was six years later, when I had a job in a local guitar shop, that the news swept into town that a Virgin Megastore was opening in Bristol city centre. Here was my chance to escape the hordes of Slash wannabes that formed the customer-base of a provincial music store in 1992. It's true, Virgin didn't feel like my natural habitat; I would have been more at home in Tony's or Revolver, or any of the city's independent record shops run by avuncular middle-aged men. But I had grand plans of moving to London, where I had heard the streets were paved with coloured vinyl, and here I saw an opportunity to use Richard Branson to my advantage. Two interviews later, I was thrilled to receive an offer for the Sales Assistant post in the Specialist Music Department, which covered rock'n'roll, blues, country, folk, world music, easy listening and jazz.

My role kept me sealed off in my own section at the back of the store, away from (in my impassioned teenage opinion) the distasteful electronic beats of the Dance department, the tedious grunge of Rock and Pop, and worst of all, The Chart – a vast display of the Top 40 singles that dominated the store's front entrance.Yes, I was wildly out of step with my colleagues' music tastes; I didn't own any Nirvana CDs, or indeed, a CD player. But I was happy in my own little world, arranging Emmylou Harris albums in chronological order, and directing my teenage lust at the early album covers of Chet Baker, whom I considered a far superior junkie pin-up than Kurt Cobain.

The job was a musical education and I soaked up every note, every name, every catalogue number. While on duty I was allowed to choose the background music, allowing me the magical opportunity to absorb a world of new sounds. From Son House to Sun Ra, from Fela to Fotheringay, my musical horizons expanded fast. The other, not so appealing, educative side of the job was my entry into corporate retail culture. My position at the guitar shop had been more akin to a bit part in The Young Ones, so it was a shock to find myself wearing a branded T-shirt and being processed in Virgin Retail's induction programme.

Richard Branson was flying high in the early 1990s. Each one of his business whims made headlines as well as profits, and his rebel-turned-millionaire image had captured the heart of every budding British entrepreneur. The suits from Virgin Head Office tried to sprinkle the initiation process with this supposed Branson grooviness but it was unconvincing; we all knew that we were cogs in his machine. Virgin was establishing itself as a corporate music retailer and any cool underground status it had enjoyed in the 1970s and 1980s had been destroyed by a rash of identical Megastores opening across the UK. An aggressive branding strategy was underway, illustrated by the mean-eyed, slickhaired Operations Director who snarled at us new recruits: "Do you understand it is essential that all our stores look the same and stock the same product?"

And there was a whole new lingo to learn, most of it ending in the suffix "-age". We didn't use signs, we used "signage"; we didn't give change in coins, it was "coinage"; the area of the shop floor was measured, not in square feet, but "square footage". Our workplace was a "store", not a "shop", but most galling to our young, ideological hearts, was that the music we loved so much was "product".

Still, my master plan was coming together. Within a few months, the news came on the internal notice-board that a store was to open in Croydon and staff were being recruited to start immediately for the set-up. I looked at a map. Croydon? That's pretty much London, I thought. The reality made itself obvious as soon as I clocked in for my first day.

I may not have been delighted to welcome Croydon into my life but, boy, was Croydon ready for Virgin! On opening day there were queues around the block. Branson himself was coming to cut the ribbon and the entire town had taken the day off work to welcome the great man to their pedestrian shopping precinct. Young men stood clutching his book, queuing patiently for an autograph while women waved hand-painted banners: "Welcome to Croydon, Virgin!" "We Love You Richard!"

The downside of living and working in Croydon was slightly compensated by two factors. One, there was a superb second-hand record shop called Beanos just round the corner from the Megastore, and secondly, I had received a promotion; I was now the Specialist Music Buyer, responsible for selecting the stock in my department.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

There were four music buyers at the Croydon store and the battle lines with the management were drawn from day one. The head office execs had taken the inexplicable decision to hire the middle-management from non-music backgrounds. Our line manager was a bloke who used to sell trainers at a sports shop in the Whitgift Centre. He knew nothing about the record business and, it seemed, nothing about music. He discussed forthcoming releases in the stilted manner of a square parent trying to speak hip to their children, mispronouncing band names or saying them awkwardly, as if trying out some strange new language. I'm sorry to say that our Monday morning meetings were a source of terror to him as he attempted to bestow his authority on us sneering buyers, who, we were all painfully aware, would have hammered him in a pop quiz. But how could we possibly respect a man who pronounced compilations "compliations"?

Despite the backroom bonhomie, my move up the M4 had landed me in musical isolation. Croydon's record shoppers fell into two camps: schoolboy DJs who fought over the latest dance 12-inch, and OAPs who peered over their eyeglasses at Flanders & Swan tapes. Certainly no one in Croydon wanted what I was peddling in the Specialist Music Department. The day a customer bought a Guy Clark album, I almost leaped over the counter and hugged him. Unfortunately, the management had yet to understand our customer demographic and somebody made the decision to get Malcolm McLaren in for a book-signing. He sat behind a table by the front door with his pen and his pile of hardbacks, and he waited. All day. Around 4pm, one ageing punk stumbled in and asked for an autograph. He didn't even buy a book.

Mercifully, my prayers for deliverance were answered and the role of Specialist Music Buyer at the Oxford Street branch came up for grabs. This was the one I had been coveting – the big London flagship store where I could get stuck in to curating my own department. I took the bus up to town for the interview and met the departing buyer who was reassuringly surly and superior and presented me with what was essentially a fiendishly difficult music quiz that covered every section of the Megastore's vast Specialist Music floor. My years of autodidactic immersion had paid off. I breezed through the test, surprising myself as the answers to Youssou N'dour's home country and Pentangle's guitarist flowed from my biro. I may have even made notes in the margin about Mongolian throat singers. I got the job.

I soon settled in on the top floor of the giant Oxford Street Megastore. This was a heyday for Virgin and the flagship store was a true music mecca, populated by both staff and customers who genuinely loved records. Behind the scenes, the rift between the suits and lower ranks proved healthy and provided us buyers with the great bond that is a common enemy. There was an uprising in our office when some new upstart manager cooked up the idea of sending us out to work stints on the till. It was as though we'd been promoted to general and were now being sent back into combat. We had all done our time out there and as far as we were concerned, the womb-like sanctuary of the buyers' office, (plus the imagined importance of our positions) was our reward.

The shop floor was a war zone and we preferred to stick together in our sweaty, windowless office where we would carouse with the label reps, engage in heated debates about Jeff Buckley and spend the rest of the day trying to look busy as we studied mammoth computer print-outs of our "product". I was in my element. Most of my school friends were now at university reading English or Philosophy; I was in a messy noisy stockroom, reading the liner notes from a Sun Records box set. I wouldn't have swapped places for anything.

My domains at the Oxford Street store were the Country, Rock 'n' Roll, Blues and Easy Listening sections but the scale of these was huge compared to the Croydon or Bristol branches, and I had much more scope to mould my department as I wished. And so the sections expanded, extensively, to include the outtakes of obscure Mississippi bluesmen, mind-bending Theremin collections and Japanese bluegrass bands that had made one album in 1974. The section for birdsong CDs (bought solely by Bill Oddie) was shrunk to make room for London's finest selection of rockabilly vinyl. Promotional displays reflected my own musical tastes, except for when Head Office intervened and ordered a Garth Brooks campaign. This was the height of the New Country phenomenon and there was no getting around it. Fortunately, the campaign titling was in my jurisdiction so I delved into the box of magnetic letters and headed up the display THE ANTI-HANK. My manager stared at it, confused: "Change that signage, people won't understand it". The dumbing-down had begun.

It was fun while it lasted but the writing was on the wall. The diktats from head office were getting stricter and any personal touch from the staff was discouraged. Individual curation and eccentricity, the backbone of any good record shop, was being driven out. I left the Oxford Street Megastore in 1997 to work at an independent record label and watched Virgin's decline through what remained of the 1990s, as HMV lived up to its top-dog name on the high street. The industry commentators said HMV had succeeded because of its diverse range, whereas Virgin had made the mistake of aiming squarely at the mainstream and ignoring true music fans. Hah! Vindicated at last. But I guessed that my selection of obscurities had long since been boxed up and sent back to whence they came. Despite all their business jargon and MBAs, the people at the top had simply failed to grasp that selling music was not the same as selling trainers.

My record shop days are long gone but I still miss the morning camaraderie of a stockroom on new release day, or the opinionated discussions of the Oxford Street buyers' office. More than that, I miss record shops. A few of the old guard remain and it's not all bad news on the high street – independent record stores are on the rise for the first time since the mass closures of the early 2000s. Vinyl has found a new league of fans – and as of this week, its own charts – but it's more of a boutique affair than the days when you picked up an album with your newspaper and fags at John Menzies.

The era of every small town having its own independent record store, complete with eccentric owner who would mould the tastes and, indeed, lives of music-mad kids like me are over. Even the once-mighty behemoths could not hold back the tide of Napster, iTunes, Amazon, MP3s and Spotify. Not so long ago, the idea that the record shop would need a dedicated awareness day would have been laughable – every Saturday was record store day - but the way the world listens to music has changed, as have the ways we buy it, if at all.

The business may have been transformed beyond all recognition, but I and many others will recall the excitement and bonhomie of record-shop life, the joy of being surrounded by music and the people who love it, day-in, day-out. We were overworked and underpaid but I lived, listened and learned a lot in those few years. And I'm still pretty handy in a pop quiz.

Saturday 18 April is Record Store Day: www.recordstoreday.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments