How One Direction became the world’s first internet boyband

In the 2010s, a group of boys on a British reality show became modern pop messiahs. Their success was built on an innovative blueprint of international support on social media, writes Douglas Greenwood

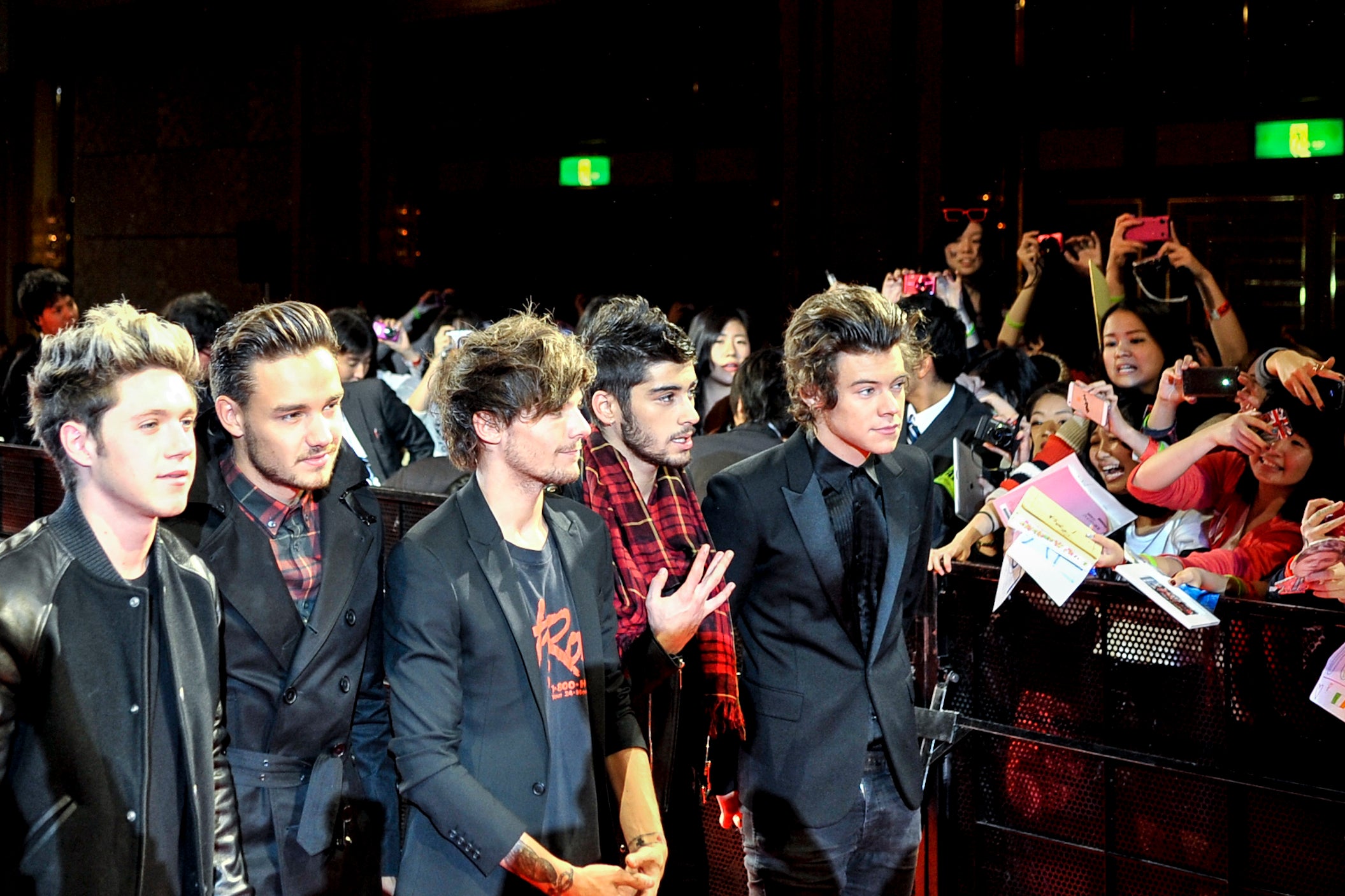

Ten years ago today, five teenage lads – Liam Payne, Louis Tomlinson, Zayn Malik, Niall Horan and Harry Styles – were thrown together in the audition stages of The X Factor. They were chosen for their singing ability, sure, but just as important were their bankable good looks and cheeky sensibilities. Somehow, One Direction only finished third – but as an army of online fans assembled and grew around them, the boyband became the first of their kind to have their enormous legacy documented in real time. By the time they disbanded in 2016, the most successful pop act to come out of Simon Cowell’s long-running series had sold in excess of 11 million records worldwide.

One Direction had a recruitment and promotional technique that no boyband before had ever utilised properly: the internet. At the beginning of the 2010s, as CD singles made way for more easily accessible streaming services, the music industry took what would become its most significant turn towards a digital future. Fan clubs, once the product of torn-out subscription pages from teen magazines, naturally moved with them, too. The advent of YouTube a few years earlier had not only birthed stars whose voices were seldom heard beyond their bedroom, it gave pre-existing ones – One Direction included – a more transparent connection to their fans online. The sign of an OG Directioner can be marked by the moment they started exercising their fandom; the long-term ones who watched their digital presence grow were there from the 2010 “Video Diary” days, in which the group would upload weekly insights to their life from The X Factor house on YouTube.

Whenever they were on tour, there were new things to talk about every day, so that encouraged fans to spend a lot of time on Twitter engaging with other fan accounts

“The comments [on those Video Diaries] were a place for people to share their thoughts,” says Amy Astrid, an online content creator and long-time One Direction fan. “It made their growing audience feel like they really knew the boys.” But while those clips soon petered off as the group grew bigger, enrapturing a teen and adult audience across the country (by the live final, over 17.2 million people were watching The X Factor that year), fan communities were growing on social networks like Twitter instead. Astrid’s own follower count is still over 160,000, most of it cultivated during the years in which One Direction were active. “Whenever they were on tour, there were new things to talk about every day, so that encouraged fans to spend a lot of time on Twitter engaging with other fan accounts,” she says. “I definitely noticed spikes of growth in followers and retweets around those time periods.” When Justin Bieber, another subject of modern stan culture, followed her, she gained 24,000 new followers in a week.

Forums and fan clubs were commonplace online by the time One Direction became famous, with the likes of PopJustice, launched in 2000, and the Britney Spears-led forum BreatheHeavy.com, launched in 2004, becoming pivotal places for pop discourse online. But One Direction’s rapid ascension to fame called for a new kind of immediacy when it came to 1D news. Twitter was, Astrid says, a place “where fans could interact with one another directly and form a sense of community”. So-called update accounts, designed to retweet and share every morsel of information about the boys’ lives and careers, became resources for fans and a digitising culture news media that saw traffic potential in the lives of these five men. The most popular, @STYLATORARMY, founded in 2010 by a then-13-year-old, has one million followers.

During One Direction’s chart reign, journalist Carl Smith was the editor of Sugarscape.com, a now-defunct digital extension of the teen girl magazine Sugar that covered celebrity culture and lifestyle news for 16-to-24-year-old women. “Nobody could have predicted the impact they’d have on the teen journalism industry,” Smith says of One Direction’s influence on that sector. “That concoction of reality TV and social media overtaking the print market in our field was such a cultural zeitgeist of the mid-2010s. We were learning to navigate this new world on the job.”

Pre-Twitter, most fansites relied on news outlets to report stories that they, in turn, would present to an artist’s fanbase. But One Direction’s worked in reverse. “We’d often cite 1D update accounts as our main news source,” Smith says. “Fans knew the band’s every move and – nine times out of ten – reported something or provided a lead on Twitter before anybody else.” He calls the relationship “symbiotic”, but also stresses that, when it came to debunking rumours – like the claim that Styles and Tomlinson were in a sexual relationship, colloquially referred to as “Larry” by those who believed it – Sugarscape had a “duty to report with integrity” as a reliable, fact-checked news source.

The social media frenzy that formed in the wake of any 1D development was a symptom of their fanbase’s collective power. While measurements of success were often tied to album and ticket sales, here anybody who had a love for the group and an internet connection could have their voice heard and their head counted. Astrid recalls creating hashtags tied to the group and watching them go viral, helping the band win big at voter-based awards shows like the Teen Choice Awards. The band won 28 of the 31 prizes they were nominated for. “It really made you feel like you had a voice,” she says.

It would have been some kind of outlet to be open and share my excitement and love for the boys, rather than keeping it to myself

But not all One Direction fans could participate in the quick-moving hysteria of their digital presence. Tom, who’s now 24, was a queer, South Asian, male fan of the group. He bought their merchandise and listened to their music in secret, but his family’s strict policy on what he viewed online meant he couldn’t engage fully in those digital communities. “I remember girls at school who would talk about things on 1D Twitter, and I would listen in while also pretending I didn’t care as much as I did,” he says. Beyond the schoolyard, the group’s massive Twitter community provided fans with a space to discuss and debate the 1D discourse around the clock. For those who were teased about their admiration for the boys in person, it was a place they could be understood, too. “I wish I had that,” Tom adds. “It would have been some kind of outlet to be open and share my excitement and love for the boys, rather than keeping it to myself.”

That a fan community has operated so intensely via social media, to the point where it shut out fans who could only engage with it in real life, is a testimony to just how unprecedented One Direction’s situation was back in the early 2010s. It also proves how much those communities have adapted since then. The intensity of 1D’s internet presence (across Twitter, but equally so Tumblr and the fan-fiction site Wattpad) widened the net to introduce fans from further afield – those who felt distant from the heavily white European and American fan cultures. Miselo grew up in Zambia, and has been a One Direction fan since the Video Diary days. Now, she calls herself a “Harry girl”.

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

“Because I was living in the middle of sub-Saharan Africa, I knew I’d never see them live,” Miselo says, accepting the internet as the one way she and her friends could engage fully with the 1D fandom. “I didn’t have Twitter back then, so I mostly used Tumblr and Wattpad a lot. A friend and I got really close actually when we had a sleepover-slash-listening party and she told me about After.”

After was a three-part, novel-length fanfiction written by Anna Todd, about an 18-year-old girl’s love affair with Harry Styles. The story has been read over a billion times by One Direction fans online, becoming the inspiration for a Netflix film of the same name, released in 2019. Becoming a 1D fan, says Miselo, “is what made me friends with a lot of girls in my school that I wasn’t friends with before, because we had ‘nothing in common’. We used to watch all the Video Diaries and send Facebook memes to each other. And then we turned into legitimate friends.”

Being a Directioner was the first time I ever considered what my ‘tastes’ were

The internet is a treasure trove and a minefield for young people coming of age – as much a source of animosity as it is a place where their interests are treated with respect, the power of their support made clear. Over time, formats created by Directioners have become integral in the birth of online fandoms that have followed.

In the four years since One Direction went on indefinite hiatus, the fandom has splintered, choosing to support their favourite member in their solo careers. But it has also opened the door for the likes of BTS, the behemoth K-pop group, and their so-called fan ARMY, to make use of the methods 1D fans helped create. In 2020, these methods have pivoted towards altruism, too. BTS fans famously banded together to match a $1m donation to a Covid-19 relief fund to match what the group donated. In the wake of police brutality during the Black Lives Matter protests, K-pop fans online flooded apps designed to identify those protesting with “fancams” (short compilation videos of their favourite stars set to music), crashing them and rendering the platforms unusable.

Time has helped to prove a point that the teenage fans of One Direction have known all along: that there was nothing fickle about fandom. The power of teenagers, particularly teenage girls, has been historically overlooked in the music industry. To Miselo, who now studies philosophy and classics at college in the US, the general response from others back then highlighted “how easy it was to dismiss what girls liked, just because girls liked it. Being a Directioner was the first time I ever considered what my ‘tastes’ were. It made me open to ridicule, but it also made me aware that I could be on to something that people won’t get until later on, or maybe never at all.”

As the world becomes beguiled by Billie Eilish, and pats BTS fans on the back, it’s important to remember that there were tens of millions of young people –particularly young women – who had been building this blueprint in real time. Ones whose love for five regular lads from Britain changed fan culture as we now know it.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies