Leftfield interview: ‘Music used to be about a position’

After 16 years, the seminal dance act are back, but as just one man

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

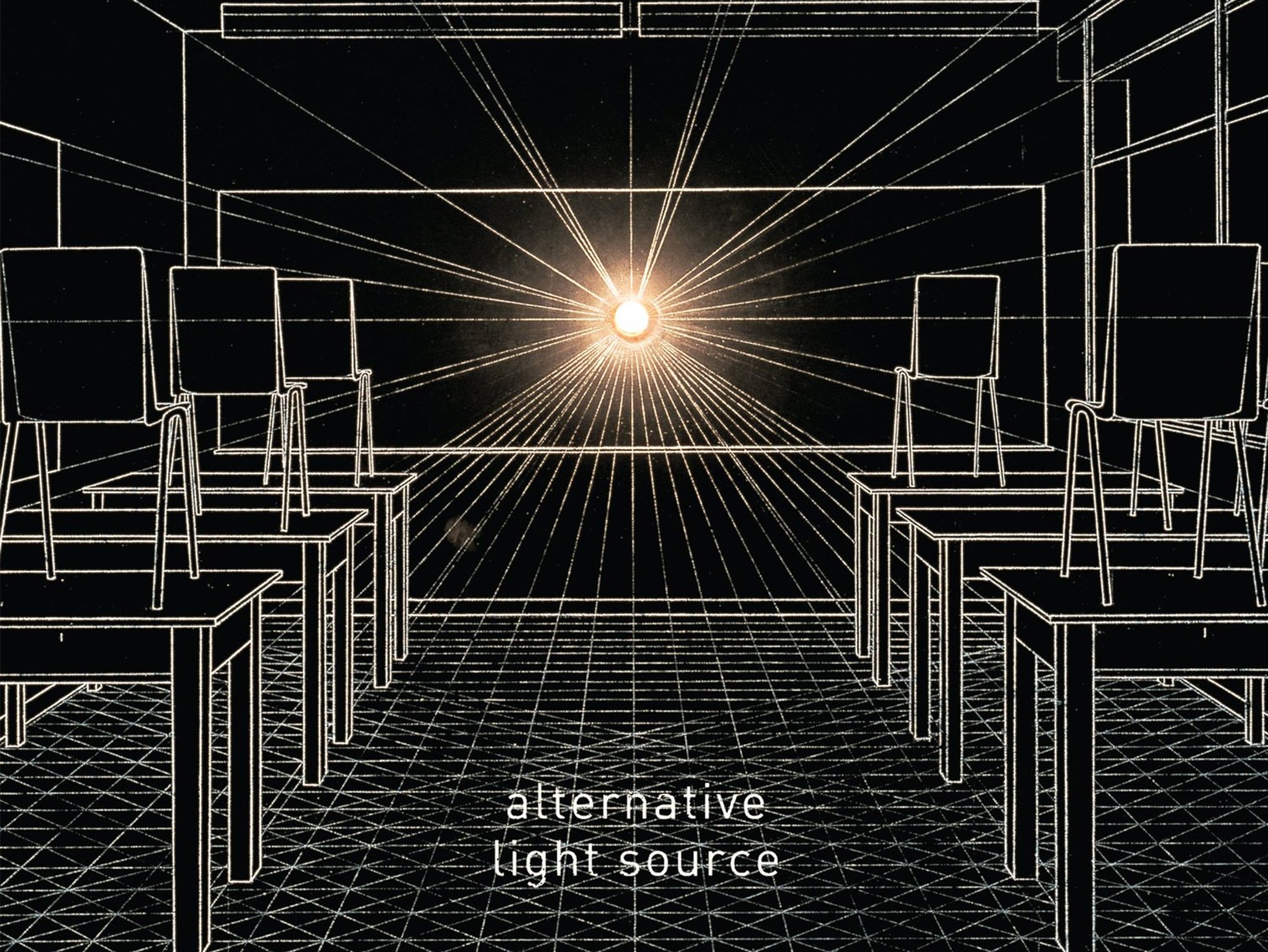

Your support makes all the difference.It’s been 16 years since the pioneering dance act Leftfield last had an album out – quite a career break by anybody’s standards. Their last LP, Rhythm and Stealth, was released in 1999. Babies born at the time will have been wrestling with their GCSEs when its follow-up, Alternative Light Source, finally emerged earlier this week. That’s how long it’s been. In the interim, we have seen the rise and fall of electro-clash, dubstep and grime, and the rise and rise of Apple and Spotify, smartphones and Snapchat. Everything has changed. The question is: where does Leftfield now fit in?

“I honestly don’t know,” says co-founder Neil Barnes, when we meet near London’s Portobello market, not far from his house. “When I was making the new album, I didn’t really think beyond whether it would be something I like.”

The “I” is significant because Leftfield used to be a duo. The other founding member, Paul Daley, hasn’t been involved since 2002. Their working relationship was famously strained, but when they gelled creatively, it was to seminal effect. They even invented a new style of dance music, a multi-layered, magpie-hybrid of electro, house, dub, punk, folk and film scores, entitled “progressive house” by the music press, and widely copied by a legion of bedroom producers (with mostly forgettable results).

Barnes and Daley proved that dance acts could make coherent albums too, with their 1995 debut Leftism and 1999’s Rhythm and Stealth, both nominated for the Mercury Prize. Well-chosen guest vocalists, from John Lydon, on breakthrough single “Open Up”, to Afrika Bambaataa and Roots Manuva, added the stardust, which compensated for the duo’s introverted personas. They were always more suited to the studio than the limelight – a fact savagely highlighted by the NME, which cropped both their heads from a cover shoot promoting “Open Up”, leaving just Lydon’s in the frame.

Barnes is reluctant to discuss Daley now, except to say that it “wasn’t always easy”. They are not in touch. He initially shies away from difficult subjects, notably his struggle with depression; he recently told the NME that, at its worst, it can make him feel “like there’s no way out”, and that music is his “safe place”. Today, he is mostly upbeat, though he tells me he won’t read the – mostly glowing – reviews of the new album because “negative stuff can make you feel funny about things” and could affect rehearsals for his new live shows.

Barnes released no music at all between 2002 and now, although he says he never stopped making it. “The Noughties was an odd time, really,” he says. “Rock and indie were so big during that decade. I was head down, in the studio, trying to work out whether I had a future.”

The seeds for ALS were laid back in 2010, when promoters sounded Barnes out about reforming Leftfield for a tour. He contacted Daley, who declined, but gave his blessing to proceed without him, and the ensuing live shows “gave me this whole yearning to do something new with Leftfield”. The pulse-quickening beats, widescreen instrumentals and satisfyingly chunky electro are all still in the mix – though the new Leftfield’s vibrant electronic palette no longer includes the dub-reggae-crossover sound the band famously pioneered – “I’ve moved on; I had to.” There is energy and introspection, light and shade – and melody too, thanks to an in-vogue roster of singers including TV on the Radio’s Tunde Adebimpe; Poliça’s Channy Leaneagh; and soulful newcomer Ofie – who sings the album’s closer, “Levitate for You”, originally intended for George Michael. (“I’d still love to work with him, but not Disco George – I’m more interested in Dark George.”)

Every Leftfield album has been the product of conflict, and ALS has been no different – only this time the conflict was all inside Barnes’s head. “It’s been a battle,” he says. “Sometimes the tunes would sit there for months and I couldn’t bear to look at them.”

Despite feeling “spoilt” by the amount of music technology now available and the possibilities it opens up, Barnes still admires the “simplicity and repetition” of punk and reggae, both of which he also loves for their “original anger”. “That’s one of the things with Leftfield that gets overlooked – there’s a bit of pissed-offness as well.” At one point during the rave years, they turned down a request from the Conservative Party to use one of Leftfield’s songs – Barnes can’t now remember which song, or what for, but insists that it remains “the most ridiculous thing that ever happened to Leftfield”.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

What’s pissing you off right now, I ask, and it’s like flicking a switch. “Almost everything to do with music at the moment,” he spits. “Music used to be about a position and about standing your ground – and now it just feels like we’re all sucking it up. I still try my best to put my finger up to everything.” Hence why he chose to work with Jason Williamson from electro-punk poets Sleaford Mods on “Head and Shoulders”, which contains a typically sarky diatribe from Williamson against cokeheads. “At least he’s got a bit of an attitude … what I’m trying to say is maybe – just maybe – music isn’t as important now. It’s just wallpaper, a lot of it. And maybe people are looking for something else to express their attitude in. I don’t know what. But young people, they’re into a million other things.”

If this is reading like a middle-aged rant – Barnes is 54 – then at least he is displaying the same passion he had as a younger man. And there are plenty of young artists he rates, such as Run the Jewels and Kate Tempest – “She expresses youth culture in a really refreshing manner”. Though he may be being a little partisan here; his 25-year-old daughter, Georgia, plays drums for Tempest and recently signed a record deal of her own with the independent label Domino. “So, maybe what I’ve just said is a load of bollocks,” he grins. “Music is the most important thing still!”

“And in a weird way, Alternative Light Source is about the power of young people. It’s about the idea of something new coming out of nothing. It’s about coming out of bad moods and exploding into a really positive vibe. It’s also about looking to the youth. That’s what I still believe in.”

‘Alternative Light Source’ is out now on Infectious. Leftfield plays Albert Hall, Manchester, on Thur and Barrowland, Glasgow, on Fri and Glastonbury on 27 Jun. Tickets from ticketmaster.co.uk.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments