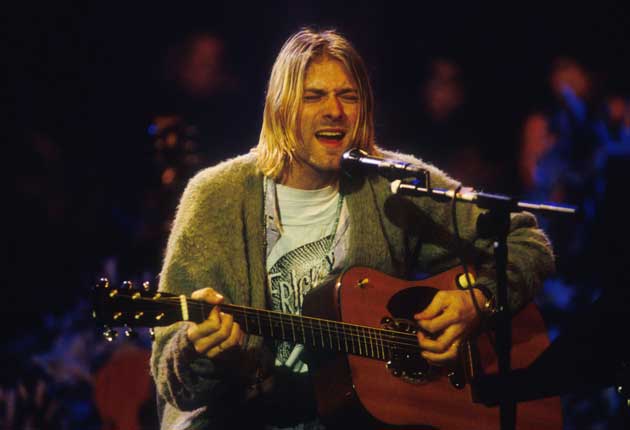

Kurt Cobain: The play

As a new play about Kurt Cobain opens, Nancy Groves considers the frequently discordant history of bands in the theatre

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The night that Who drummer Keith Moon smashed his Rolls-Royce into the side wall of the Royal Court Theatre and broke into Helen Mirren's dressing room, demanding to join her on stage, is a rare anecdote shared by both the theatre and rock fraternities.

By 1974, "Moon the Loon" was infamous for his toilet pyrotechnics and creative assaults on hotel rooms. Some might say he invented the genre. The incident was more notable for throwing light on the play in question – David Hare's Teeth'n'Smiles – in which a heavy-rock band on the point of implosion turn up to play an Oxbridge May Ball. Despite a cast including Mirren, Cherie Lunghi and Antony Sher, Hare's third play was not his best. A recent revival at the Sheffield Crucible received lukewarm reviews. The problem? Real rock'n'roll invariably trumps its fictional counterpart, as Moon's theatrics during the original run seemed to prove.

Can theatre and rock music ever mix? It's a question that rears its poodle-haired head every few years or so. Whether the answer is to be found in anything other than a greatest-hits medley hung on a paint-by-numbers plot is another matter. The new play this time is Nevermind, a fringe piece at the Old Red Lion Theatre in Islington, North London about a manic depressive music journalist visited by the ghost of Kurt Cobain.

"I've always been interested in writing about music," says its author Martin Sadofski, erstwhile vocalist in Bradford-based indie band The Passmore Sisters, who recorded two Peel sessions back in the 1980s. "But Nevermind is a play about failure. The main character, John, is facing a battle of whether to take his life, or to make something of it. And Cobain appears as his alter ego: a success who couldn't deal with it, as opposed to John, a failure who can't deal with it."

For Sadofski, who also has a BBC4 film about Marvin Gaye in the works, musical heroes are ripe for characterisation. "The thing with musicians is that they put on a front. People get into bands not to be themselves but to be someone else. And when it all starts to crumble, due to drink, drugs or simply because their music has become passé, the submerged personality tends to come out. I think that's their appeal for writers."

Why then do so few playwrights manage to convert the subject into something meaningful on stage? Many have tried, not least Hollywood actor Christopher Walken, whose surreal exploration of the afterlife of Elvis Presley, Him, debuted at the 1995 New York Shakespeare Festival with its author in the lead role. A cult hero in his own right, Walken got mixed reviews. While the New York Times praised "the sharpness and wit of the writing", other critics called his play "a farrago of nonsense", "garbage" or worse, "maudlin masturbation".

Similarly, British reviewers deemed David Harrower's 2000 play Presence, which dramatised The Beatles' early residency at the Star Club in Hamburg, a limp affair in comparison to the rest of his oeuvre. Their main criticism? That Harrower had mislaid half the Fab Four from his script. Whatever happened to creative licence?

Perhaps, suggests Robert Graham, author, playwright and lecturer in creative writing at Manchester Metropolitan University, adulation is simply not a good starting point for writing. We talk of fan literature but rarely use the term to denote quality. Graham's own Smiths-inspired drama, If You Have Five Seconds to Spare, played a short sell-out run at Manchester's Contact Theatre in 1989, but, significantly, Morrissey did not feature. Instead, the play revolved around your typical angst-ridden Smiths obsessive holed up in a bedsit.

"Most of us," says Graham," no matter how big a fan of music we may be, don't know that much about the reality of life in the music biz, or what Morrissey or Lennon or Elvis are really like as people. What we do know about is the experience of listening to a song and completely empathising with the feeling that the words and music together make. And that, to me, is where imaginative writing and popular music may have a fruitful relationship."

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Except perhaps for old Moz. Graham and the singer shared a hairdresser at the time and thanks to Dave the Demon Barber, Morrissey received a copy of the Five Seconds script to read. "At my next haircut, Dave reported his reaction, which was 'What made me think he would like it?'," says Graham. "I can laugh now I've got no hair and Morrissey is losing his."

"Reminiscences of rock heroes can be tedious," wrote one reviewer of The Ballad of Crazy Paola, Flemish playwright Arne Sierens' tribute to one couple's hedonistic music past, which played in translation at London's Arcola Theatre last autumn. The same could be said of reunions. Few can forget (though writer Andrew Upton, aka Mr Cate Blanchett, may wish to) the recent London run of Riflemind, a clumsy comeback tale about a once-great band that even director Philip Seymour Hoffman could not save from early closure at the Trafalgar Studios. In the words of The Independent's Paul Taylor: "God knows, the deliberations that must have dragged on in order to bring the no-longer-boyish boyband Take That back... I would prefer, though, to sit through a dramatisation of the minutes of those meetings than take another look at this show."

Like real rock reunions, the boredom and/ or cringe factor of watching a bunch of old codgers on stage can be too much to take. But there are exceptions. Mike Packer's 2007 hit, tHe dYsFUnCKshOnalZ!, at the Bush Theatre brilliantly satirised a fictional punk band re-recording their anarchic anthem "Plastic People" for a credit card advert. Critics praised the sub-Spinal Tap knowingness of the piece, but also – rare for such a play – the music, which was performed live in front of a wall that crashed down in a cloud of dry ice (with no Keith Moon to help it).

And talking of Plastic People, there's Tom Stoppard's Rock'n'Roll, an epic mash of pop and politics that, perhaps more than any other play about music, laid adequate claim to its own title. During years of political and social upheaval in Czechoslovakia, The Plastic People of the Universe were a band who refused to compromise either their music or their morals. That Stoppard did not compromise them in turn is perhaps why Rock'n'Roll is his best play since Arcadia.

When the final scene cuts to a live track from the Rolling Stones' album No Security, it's not laziness on the playwright's part, but because the music says all that needs to be said. "Rock'n'roll doesn't necessarily mean a band," Malcolm Maclaren once announced. "It doesn't mean a singer, and it doesn't mean a lyric, really. It's that question of trying to be immortal." Or in the words of Kurt Cobain: "If it's illegal to rock and roll, throw my ass in jail."

'Nevermind', Old Red Lion, London EC1, 16 June to 4 July (020-7837 7816; www.oldredliontheatre.co.uk). Robert Graham's short story collection, 'The Only Living Boy', is published by Salt on 1 July

Play it again: The five best rock'n'roll dramas

John, Paul, George, Ringo... and Bert (1974)

Willy Russell's first big hit about a fictional fifth Beatle played to 15,000 people at the Liverpool Everyman before a West End transfer that won Evening Standard Best New Musical of the Year.

The Stars That Play With Laughing Sam's Dice (1976)

This 1976 play by Hawkwind frontman Robert Calvert recreates an episode from the early life of one James Marshall Hendrix, and is named after an early B-side by the rock guitarist.

Kill the Old, Torture Their Young (1998)

Only one character in David Harrower's tragi-comedy is a rock star but he has some of the most haunting lines of the play.

Finer Nobler Gases (2004)

Following the drugged-out members of an East Village band, Adam Rapp's play impressed Off-Broadway but divided audiences when it came to Edinburgh's Fringe.

Rock'n'Roll (2006)

This epic tale of Czech freedom fighters, Cambridge Marxists and the fall of communism lives and breathes rock music. Tom Stoppard's most personal work and a hit on both sides of the Atlantic.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments