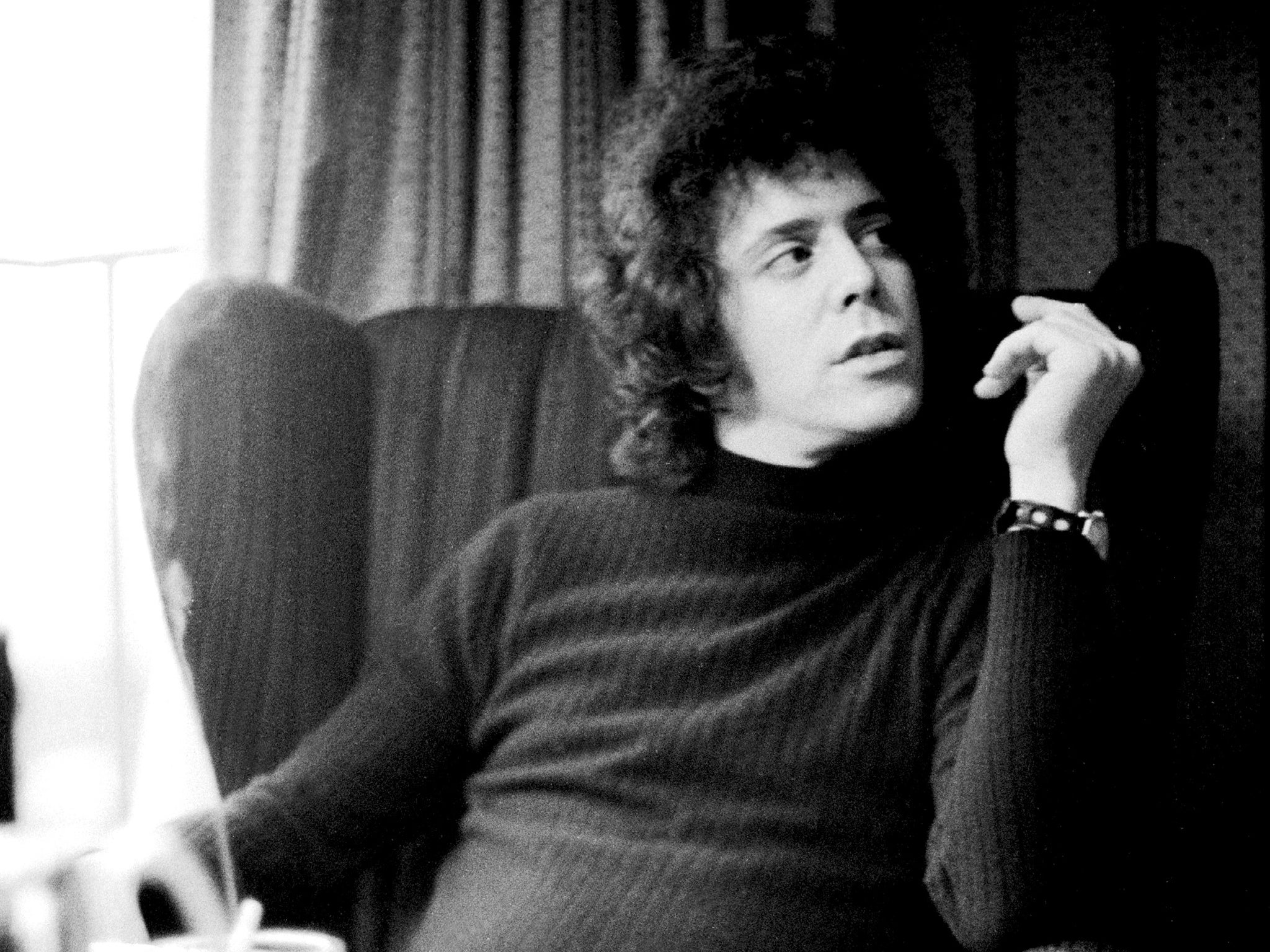

Bettye Kronstad speaks for the first time about her marriage to Lou Reed: 'Fame is a fiend. It turns people into monsters'

She recalls the highs and lows of her turbulent marriage to the troubled star

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I was a 19-year-old student at Columbia University in New York when I first met Lou Reed in 1968. I was chatting with Lincoln, a friend of his who had been his college roommate at Syracuse University, when Lou dropped by.

Little did I know of the intensity that lay ahead of us as we launched his solo career. Our relationship would last five years. We were engaged for several of those years, although we were officially married for less than one.

It wasn’t love at first sight. He wasn’t my type, but he was interesting. My first impression was that he had a serious ego, but I was perceptive enough to know that this often implies, in truth, quite the opposite. He was disarming, because he was the kind of guy who let you know how he felt about you, didn’t play any games.

I found out he was in the Velvet Underground when he took me out a couple of times for dinner, before I left for six months in Europe with friends. He was extremely stressed out, because they were breaking up, and he was embroiled in some conflict with a member of the band. When he learned I had returned from my trip, he got back in touch with me through Lincoln.

At that time, Lou was going through quite a transition. After he left the Velvet Underground, he moved back home with his parents on Long Island. These years have been called his “lost” years. Hardly. Lou came from a marvellous, supportive family, and going home gave him the safety and security to find himself again. He was writing and typing some of it up, as he worked as a typist in his father’s firm. He published several poems in Harvard’s literary magazine.

We dated for a couple of years before we moved in together. Lewis was quiet, reflective – a writer – and a teddy bear. I admired his writing very much. A simplistic explanation for why I married him could be that he wrote “Sweet Jane.”

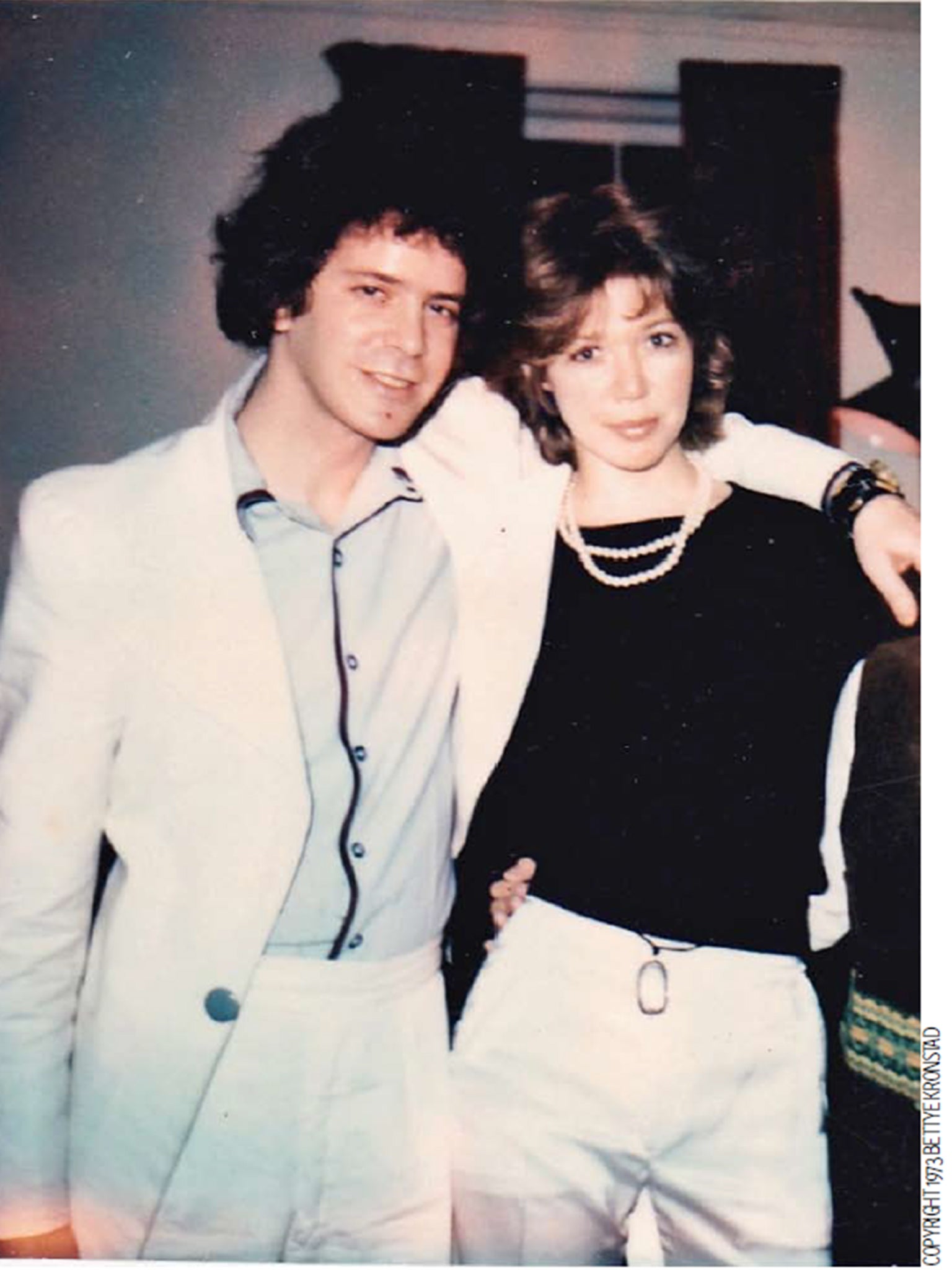

By 1970, he had left his parents’ home and we moved into our first apartment on the Upper East Side. We were married at home in 1973. I wore white satin bell-bottoms, a strand of classic pearls, a navy blue cashmere sweater, and a smashing pair of red, seriously high platform heels. Lou wore an all-white suit.

The goal of our relationship was to launch his career. I promised I would help him to make it, and put my everything behind him. I was an idealistic kid and in love. I believed in him, his talent and work. Anyone who knew Lou will tell you he trusted very few people, personally or professionally. But he trusted me. I had been embraced by his family, and he knew I wasn’t in it for the money. We were in this together: we were going to make him a star.

He put out three albums during our relationship: Lou Reed (1972), Transformer (1972) and Berlin (1973), with national and international tours to support these albums. After our first US tour, I became his lighting designer/director. I loved lighting and illuminating him and his work. We made a great team. Everyone knew that something important was happening with Lou.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

After Transformer was released, the audiences in the US and Europe went wild. They’d never seen or heard anything like him. Before Lewis, the LGBT community were oppressed and completely disenfranchised. He gave a voice to them.

“Walk on the Wild Side” changed everything. Lewis was determined to make it on a worldclass scale. He always believed the Velvets should have made it on that level, but they had failed. He was determined that would never happen to him again. The period around Transformer was a great time in our relationship, but launching an international solo career can be exhausting. Lewis was writing and recording albums. We were rehearsing for the road shows that supported them, touring constantly.

He wrote “Perfect Day” about a day we spent together in the park, exactly as he says in the song. We had become officially engaged around then. Although it appears to be a simple love song, its brilliance lies in the suggestion that love between consenting adults is never simple, always complex. He has said the most important lines of “Perfect Day” are, “You made me forget myself. I thought I was someone else, someone good.”

Perhaps I did that for him but, for me, the operative lines are, “You keep me hanging on, you just keep me hanging on,” – not only did Lewis depend upon me to keep him straight, his management team did, too.

He drank heavily, even when he was living at his parents’ house. In my naïveté, I thought all writers drank. There were no drugs in the beginning, because if there had been, I wouldn’t have been there. My job was to keep him off drugs and alcohol so he could perform on tour, meet his contractual obligations for the record company, make those albums, and design, direct and call his lights on the US tours. Looking back, I can’t believe how much responsibility was placed upon my young shoulders. But I was the only one he trusted, to whom he would listen.

After Transformer there was enormous pressure from his record company to produce another album, fulfil his contractual obligations. For eight months he couldn’t write. That’s why he became depressed. Then he’d drink more. He got caught up in a fairly familiar, but vicious cycle.

Tremendous demands were made on me to keep him as sober as possible. A fame machine this size carries colossal stakes for all involved. Things began to spiral out of control during the recording of Berlin and supporting tours. I’d already been flown in by helicopter, because it was clear he couldn’t work without me. That’s what women were taught and expected to do then – support your man. It was presented to me as part of my job, but it put enormous strain on our relationship.

He began to resent performing “Walk on the Wild Side”, because it didn’t reflect his body of work. He was disappointed and angry, because he wanted to play his “soft” songs – his ballads and love songs. But the audiences didn’t want to hear them. They wanted classic Velvet Underground hits: “White Light/White Heat”, “Sweet Jane”, “Rock ‘n’ Roll”, “Heroin” – and, of course, “Walk on the Wild Side”.

At first he was hurt. Then he realised the fine print of the contract he had with the world. If he wanted to be a star, he had to give his audiences what they wanted, because it was also what they needed. The overwhelmingly negative response to Berlin only confirmed his epiphany.

But Lewis began listening to the wrong people. Although I didn’t know it at the time, hard drugs were available during the recording of Berlin, and on its subsequent tour. He started becoming abusive again, which I could never tolerate. Fame strode on to the stage, front and centre. The guy I began dating was a sweet, quiet writer who, like most of us, had challenges. The man I left had become a monster. Sometimes fame is a fiend. It turns people into monsters until they learn how to ride it.

For many years after I exited the scene, he took a serious dive into drugs. Drugs, alcohol and their effects were the major reasons I left. He was furious I left, and angry with himself for screwing us up. We were a good team, and achieved success.

But one does not leave Lou Reed: it’s a rather serious, unforgivable breach of etiquette. I wasn’t raised around alcohol, knew nothing about it. But Lou was an alcoholic. It was incredibly sad and frustrating to watch him drink away all the beautiful, gorgeous stuff that was in him, insights that could have fed his creativity and flourish in his work.

I left him a couple of times before we married. After “Walk on the Wild Side”, his career exploded onto the world stage. It became bigger than him, me or us. He had something important to say. That’s why I stayed in the relationship long after I wanted to leave, because he said he needed me to work, and so did everyone else. After we divorced, within two weeks, I went back again.

He promised to change. But he didn’t – probably couldn’t. To assume the responsibilities and avoid the pitfalls of new-found fame, he needed more support than love provides.

I thought if I didn’t leave Lou the final time in Paris, I would die, and I’m not exaggerating. “Sex, drugs and rock & roll” began there. There were so many casualties: Joplin, Hendrix, Morrison. I’m a survivor, not a victim.

Returning home in New York was tough. I’d left a much-beloved, larger-than-life star. After finishing my final year of acting training, I moved for a couple of years to Virginia where my uncle lived. He put me back together, and got my career back on track.

When I heard about Lewis’ death in 2013, I was blindsided by grief, and completely caught off guard. I had no idea Lou’s passing would affect me so deeply. It had all been so long ago! But it got me thinking about stories from the past. I’m beginning the process of addressing some of these stories about Lou and I in the book I’m writing.

When I was with Lewis, he attained some of his greatest artistic achievements. In retrospect I think he was a lucky guy to have found me. But I’m a lucky woman for my first great love to write “Perfect Day”. It reminds me of that time in our lives, too.

Now that Lou is no longer with us, he’s even larger than life, and finally getting inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a solo artist. With Lou, rock’n’roll made an incredible leap. He gave so much it’s almost impossible to completely encapsulate his contribution, but this month [18 April], I think you can be sure he’ll be appearing in Cleveland, Ohio, where the ceremony takes place. He wouldn’t miss it for the world.

As told to Charlotte Cripps

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments