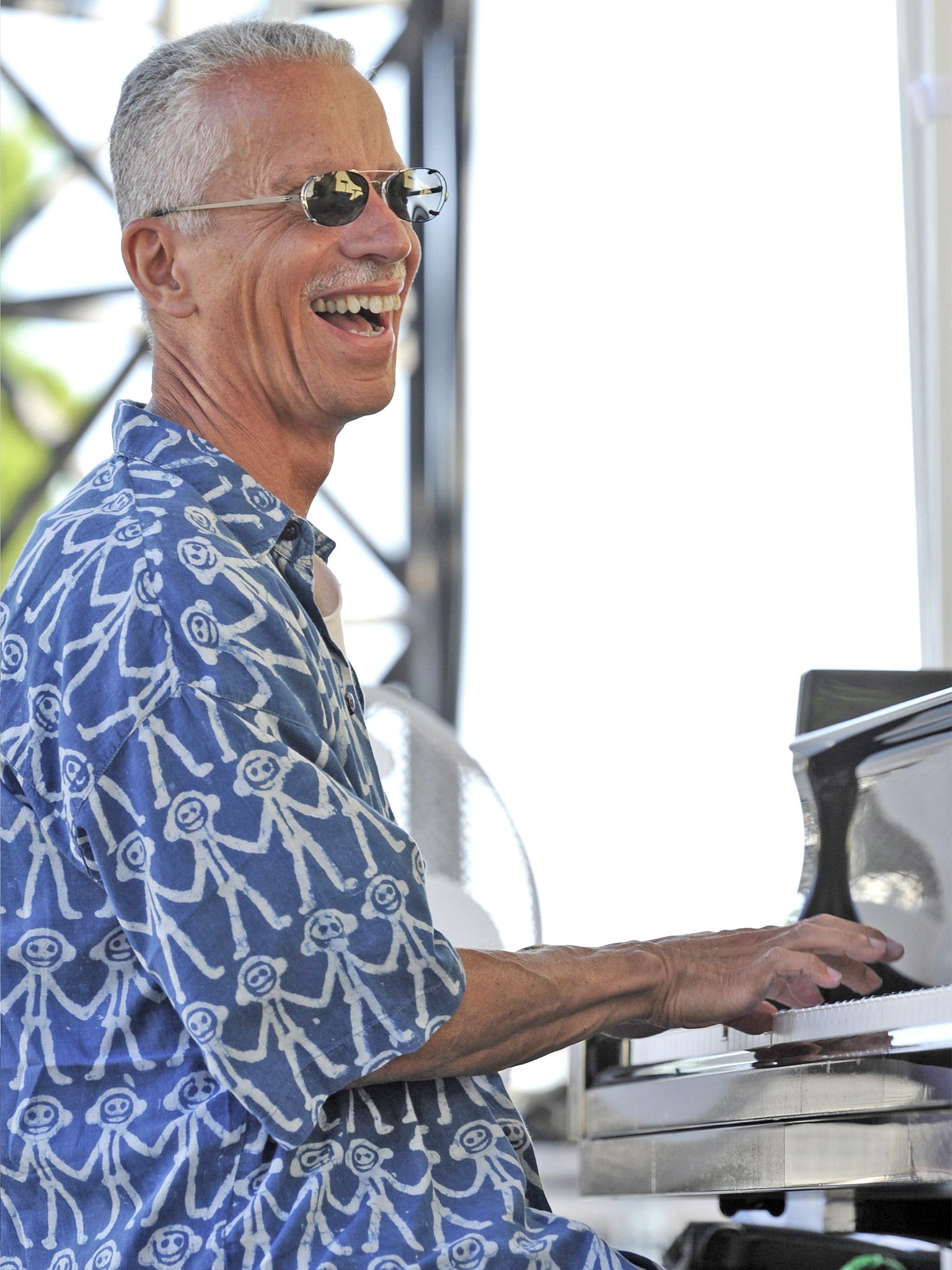

Audiences, beware: Keith Jarrett is the wild man of jazz

Jarrett has overcome illness to become one of the most influential musicians of modern times. He's also renowned for haranguing his fans, says Jessica Duchen.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Keith Jarrett is giving a solo concert at the Royal Festival Hall. Spread the word! Except that the word has already spread and the tickets have flown.

What makes one man and a piano fill a hall for solo improvisation, let alone an individual with a reputation for stopping mid-flow to harangue his audience? Well, Jarrett, 67, is a legend for a good reason. His improvisations emanate from heaven knows where, driven by a depth of conviction that's unmistakeably his, producing sounds that won't have been heard before and won't be repeated. It's as if he is plugged in to a celestial battery charger, and we, listening, connect to that astounding energy by proxy.

He performs not just with his hands and arms, but with his whole body, his shoulders curving towards the keyboard as if microscopically examining every squiggle of melody. He emits hums, whines, groans. He sits, he stands, he wiggles. Some find him mesmerising. Others say he is best experienced with eyes closed.

He reaches audiences that other jazzers don't. Hardcore classical pianophiles, those who flock to hear artists such as Martha Argerich or Krystian Zimerman, are often drawn to Jarrett for his extraordinarily expressive musicianship and the variety of colour he draws from the instrument. Jarrett had a top-level classical training in his native Pennsylvania, and the virtuoso technique he developed has certainly fed in to the unique way he uses the instrument. He thinks contrapuntally, horizontally, involving many lines and layers of music, often embedding a theme in the middle of a wide-spun texture, and allowing a new section of thought to grow organically out of a small pattern in one that's gone before. And he'll squeeze every drop of potential out of that motif before moving on to another.

Unlike most jazz pianists (Chick Corea excepted), he has recorded classical repertoire, too: solo Bach, Mozart piano concertos and Handel suites. He has even made discs playing the organ and the clavichord. This year, while his schedule includes solo improvised recitals and trio performances with Gary Peacock and Jack DeJohnette, the loyal ECM label with which he has long worked is also tipped to be releasing a new album in which he performs the Bach sonatas for violin and keyboard with the violinist Michelle Makarski.

ECM has put out his solo improvisations from Vienna, La Scala Milan, London/Paris (Testament), Carnegie Hall, Tokyo and Rio, to name but a few, helping to widen his already huge cult following. Of his massive discography, though, the Köln Concert of 1975 is still perhaps the best-loved recording, having become the biggest-selling solo album in jazz history. Strange, then, to think that, looking back, Jarrett has said he would have done certain things about it differently. He doesn't stand still. Turbulent episodes of his life affect his creative bent; he has been remarkably open about this, saying in interviews soon after his divorce in 2010 that difficult times were "a source of energy" that he could draw on in his music-making.

But even times when he had no energy at all have made a difference. Stricken with ME (chronic fatigue syndrome) for about two years from 1996, he found himself scarcely able to play. When he returned to his instrument in gradual stages, he effectively relearned his technique, assessing his sound and style and developing a less "aggressive" touch. Once his recovery was underway he spoke of how the illness had forced him to concentrate on the deeper "skeleton" of his music and remarked that he felt he was "starting at zero and being born again at the piano".

The aims remain simple, though. Jarrett has said that his intention in his solo recitals is, first, to come up with interesting music and, secondly, to make sure that that interesting music isn't something he has come up with before.

Alyn Shipton, presenter of BBC Radio 3's Jazz Record Requests, made a series of radio programmes about Jarrett soon after the pianist had recuperated from ME. "He always says he has no idea what is going to happen in the concert," Shipton relates. "And with the neurotic perfectionism that only he could apply, he records all his performances, listens back to them, then says he tries to erase them from his mind so that they won't affect his future ones."

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

His influence on successive generations of jazz musicians has been immeasurable. Simon Mulligan, a British pianist who plays both classical concerts and jazz, says that Jarrett is prime among role models for him and his peers. "It's Jarrett and Herbie Hancock," Mulligan remarks. "We all call them Keith and Herbie. I know I've been influenced by the way he shapes the arc of his music, and the detail, such as his 'portamento' playing when he decorates the run-up to a melodic note like a singer. And in terms of touch, he is one of few people who can really make the piano sing."

But Jarrett's outbursts against his audience are no fun (although there's a spoof Twitter account, @AngryJarrett, that apes them). "He's convinced that coughing is a sign of boredom and that if you're really concentrating on the music, you don't cough," Shipton comments. "He doesn't cough while he's playing, so, he thinks, why should they cough if they're listening? What people dread is that moment when something that's going well suddenly falls in on itself and he jumps up and says 'I've seen a red light, there's a camera! If you want to remember a concert, you remember the music, you don't remember it visually...'"

Audiences today, accustomed to social media-savvy performers who encouraging filming, uploading and sharing, sometimes forget that musicians are well within their rights to demand to control their own material, and to concentrate on creating it. Distraction can wreck everything they are trying to do. According to Shipton, Jarrett's CD Radiance, recorded live in Japan, is missing a section "because he lost his rag so badly with the audience, three quarters of the way through, that the last part was no good and he couldn't issue it".

ECM might record this London appearance, too. So, if you go, remember: don't cough, don't take photos and for goodness' sake don't attempt to smuggle in a recording device. Another tip: don't leave too quickly at the end. Sometimes his encores of jazz standards can be almost the most entrancing moments of all.

Keith Jarrett: the Solo Concert, Royal Festival Hall, London SE1 (0844 875 0073 ) 25 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments