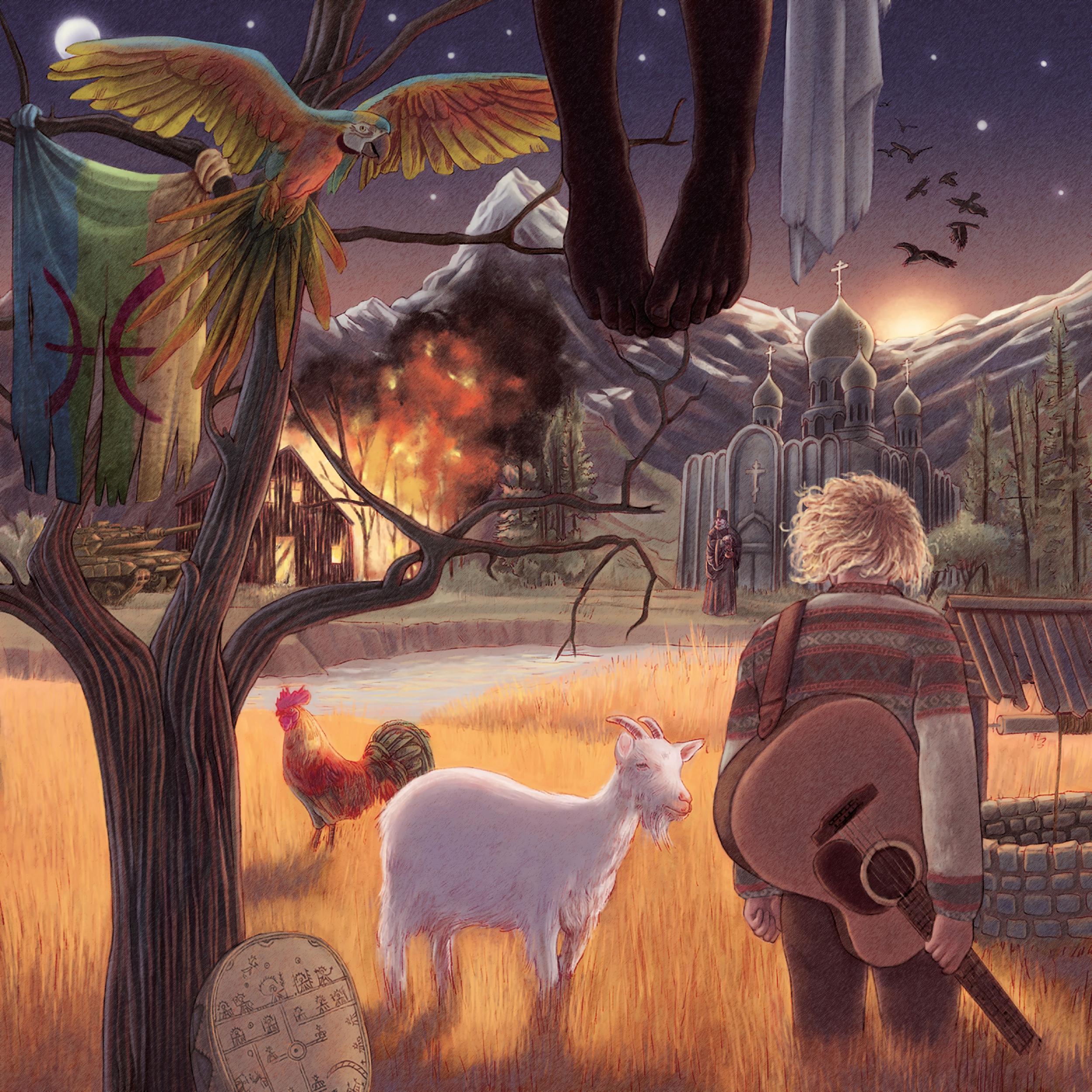

Moddi 'UnSongs': Making banned music dangerous once again

The Norwegian musician's recording is a celebration of defiance in the face of supression

When the Norwegian folk musician Moddi began collecting songs that had been banned or censored, he had no idea how much source material he would have to work with. Soon, it became apparent that there were hundreds, or even thousands of compositions for him to consider for his fourth album.

The process resulted in Unsongs, a single album of 12 compositions from around the world that were suppressed or censored in one way or another, but it could have been unending.

“I could have made 12 more albums,” he tells The Independent, speaking from Lillehammer.

Moddi, full name Pål Moddi Knutsen, has never felt that musicians should avoid politics. On the contrary, the activist and environmentalist, believes music should be a powerful platform.

The idea for the album came about in 2014 when he took the decision to cancel a planned concert in Tel Aviv, to protest against Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories. On his website, he wrote: “Silence can sometimes be stronger than music.”

After he cancelled the concert, Norwegian singer Birgitte Grimstad contacted him to tell him about Eli Geva, a song about an Israeli officer who refused to lead his forces into Beirut during the Lebanon War in 1982. While a hero of the peace movement, Geva was hated by those who supported the war. Grimstad had been warned not to sing the song when she visited Israel.

“One of the things I found is that censorship comes in so many different forms that I had not thought about before starting this project,” says Moddi.

Some of the performers whose work he has covered – Pussy Riot, the Chilean folk singer Victor Jara, the jailed Chinese poet Liu Xiaobo – were censored in very obvious ways.

Yet the power of other songs was doused more quietly; he says Kate Bush’s “Army Dreamers” was apparently removed from BBC playlists until around the time of the first Gulf War. He says even today the BBC would not explain the decision.

“I was surprised by the number of ways you can censor things in the West,” he says.

As an example, he points out how he had sought permission to film a video for his performance of Pussy Riot’s “Punk Prayer” in a Norwegian church 400 metres from the Russian border. “They said the song was not appropriate for the Lord’s room. I thought of that as a success,” he says. “Because it made the point that song was still banned.”

Another example from Norway related to the music of an indigenous people known as the Sami. For several centuries, this partly nomadic people were discriminated against, their language prohibited and their art suppressed. He decided to include “The Shaman and the Thief”, a song based on a fragment of text that dates back to 1830.

Moddi, whose 2010 debut album Floriography was hailed by Q magazine as “a heart-warming and beautifully constructed piece of melancholic folk-pop”, says that throughout his research and recording, he tried to remain true to the spirit of the original songs. As such, this meant the songs should be as dangerous and bannable today as they were when they were first censored. He says he had not removed any elements of the compositions to make them safer.

After recording was completed, Moddi says he spent the best part of a year travelling the world and visiting the countries where the songs originated. If possible, he sought out and spoke to the original performer of the song. These interviews are to be part of a website that accompanies the album.

In the case of Jara, his 88-year-old British widow, Joan, declined an interview. But he was able to speak to others who knew the activist and singer, who was killed in the aftermath of the coup launched by Augusto Pinochet in September 1973. Moddi delivers a powerful version of Jara’s “Prayer for a Worker”.

In China, he visited the jail where the poet laureate was imprisoned, but was unable to see him. In Vietnam he tried to track down the singer Viet Khang, who received a four-year sentence for “propaganda against the socialist republic of Vietnam” for his song “Where is my Vietnam?”.

Khan was released from jail in December 2015 and moved into house arrest. Moddi says the Vietnamese musicians who he spoke to were too afraid to help him get to meet the censored singer. Moddi says he was frequently asked whether it was dangerous for him to visit these countries and pursue his investigations.

“I think it is. It means I might not be able to go to these countries again,” he says. “But I still think it’s worth it. I think it’s worth it that these songs are heard.”

With a healthy dose of self-awareness, he adds: “I’m probably the least oppressed person on this planet. I’m a white man, reasonably established, and living in the West. If there is anyone should be able to perform these songs, it’s me.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments