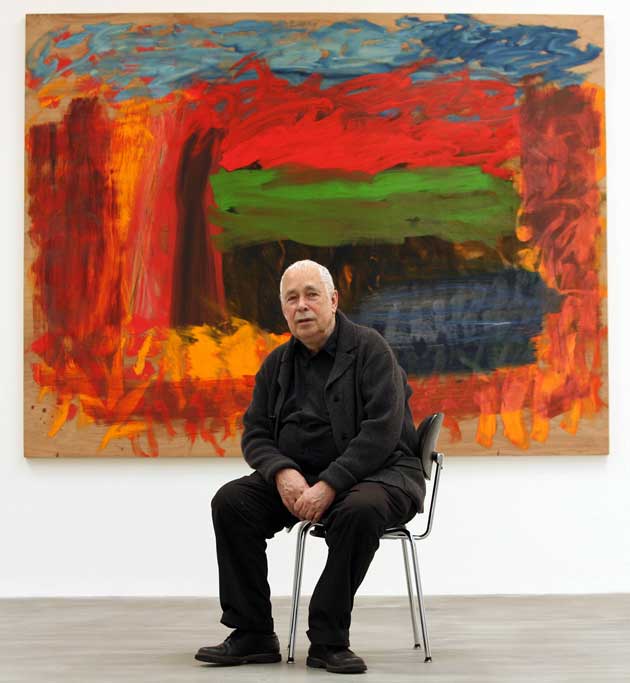

Howard Hodgkin: 'I want to set things straight'

Can knowing the story behind a painting explain it? Perhaps not. But at 76, the master of abstraction is speaking out

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Before I went to interview Howard Hodgkin, I had a fantasy. This man (who had never met me before in his life, but let's not get bogged down in boring detail), this great man, this great artist, would suddenly unveil a little oblong of multi-coloured splodges and swirls and, on a sudden impulse, beg me to take it. I'd demur, of course, but eventually I'd give in. And then I could gaze on the multi-layered jewelled iridescence of a Howard Hodg-kin painting every day for the rest of my life.

Such fantasies, I discovered on reading about him, are quite common. "These are paintings you want to covet," wrote William Boyd in Modern Painters more than 30 years ago, "paintings that boldly change your mind, that – to put it crudely – you want to steal."

And then I discovered something else. Sir Howard Hodgkin, Turner Prize winner, representative of Britain at the Venice Biennale, Companion of Honour, subject of major retrospectives at the Hayward and Tate, is, apparently, terrifying. He doesn't like talking about his work. He answers questions in monosyllables.

The face of the man shuffling painfully towards me is, however, so sweet that all fear melts. He has been ill. He hasn't, in fact, been in his studio for three weeks. But here we are, in a huge, white space, a temple to creativity. If you expect colour in an artist's studio, if you expect colour in an artist-known-for-his-colour's studio, you won't find it here. The floor, the walls and the ceiling (a vast, glass canopy) are all the exact same shade of powdery white. There's a table covered with tubes of paint, and another with brushes, but the furniture in the centre of the room is draped in off-white sheets and the pictures on the walls are all concealed by off-white canvases, and the pictures on the floor are all turned to face the wall. This, you might think, was the studio of a man whose eyes, like those of an albino at risk of exposure to bright light, might be scorched by colour.

And it is silent. It's a stone's throw from the British Museum (where he could, if seized by impulses like mine, nip out to nick one of the exquisite Indian miniatures he collects and adores) and round the corner from bustling Oxford Street, but this Victorian dairy-turned-studio, connected with a little foot-bridge to the Georgian house he has lived in for more than 30 years, could be in a field, could be in a desert. And as I sip the coffee his partner has deposited, before tactfully retiring, and gaze around at the whiteness, I feel strangely suspended in time and space. The world feels far away. This, clearly, is a place where what matters is the world inside.

The journey from the door to the chair where I'm sitting is torturous, a metaphor, perhaps, for the protracted, painful process of producing a Hodgkin painting. When, finally, the slightly monkish figure in grey and black is helped by his studio assistant, Andy into his chair, there's a collective sigh of relief. There is, however, it soon becomes clear, nothing lumbering about the brain.

"So," I say, seizing the bull by the horns or something like it, "Andrew Motion, who I saw at a poetry reading last night, tells me that you're less reluctant to talk about your work than you used to be. Is that true?"

There's a long pause. "Yes," he says in the end, "I think that's probably true. It's a feeling of wanting to put the record straight. Partly also that you know what dreadful misconceptions are lying about and want to correct them." Well, fair enough. Howard Hodgkin is 76. At the peak of his powers, as catalogues say, but no longer in the pink. Who wouldn't, contemplating a path strewn with (real or imaginary) errors, want to sweep a few of them away?

But, I venture, in an argument against this interview, against, indeed, my job, is there any particular reason why any artist other than a writer, maybe including a writer, should be able to speak particularly well, or illuminatingly, about their work? Art and language are, after all, entirely different mediums.

Another long pause. Oh dear. "I couldn't," says Hodgkin eventually, in that clipped, throaty voice that reminds you of his background, his Eton, his Bloomsburyesque relatives (Roger and Margery Fry were cousins), "agree more".

Five minutes into the interview, we have both agreed on the uselessness of what he has called in the past "the tyranny of words". Which gives me a warm glow but could, one might argue, be seen as counterproductive. So, I decide to mention the best of the many words I have read about him. In a catalogue produced by the Gagosian Gallery there's a speech by Seamus Heaney, given at the opening of the 2006 Hodgkin retrospective at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin. Heaney begins by quoting Philip Larkin's poem "The Trees". "The trees are coming into leaf," the poem begins, "Like something al-most being said." It ends with the suggestion of a metaphor. "Last year is dead, they seem to say, / Begin afresh, afresh, afresh."

It seemed the perfect statement about Hodgkin's work, I tell him, the perfect statement about pretty much everything, in fact, and when I read it, it made me cry. Hodgkin's sweet, open face crumples up and his rheumy eyes fill with tears. Ten minutes in and we're both welling up. For God's sake, Christina, get a grip. So, here's Larkin, here's Heaney and here is Howard Hodgkin crying. Is he, I ask, unnecessarily, a poetry lover?

"Oh yes," he says. And who does he return to most? "You'll be horrified," he says. "Stevie Smith." I am not horrified. I tell him that it makes perfect sense. That the poet who wrote that a character in one of her poems was "not waving, but drowning" achieved a level of perceived simplicity, naivety even, which was powerful and moving, but which often worked in quite complex ways and that, like all good art, was more powerful and moving the more you engaged with it. And that that was not unlike the work of an artist called Howard Hodgkin. Was it?

Hodgkin looks as though he is torn between laughter and tears. "Well, what else is there to say?" he says. Well, I say, pointing at the tape recorder, could he please have a go? "I think," he says obediently, "the naivety of Stevie Smith is one of the things I have in common with her and in the past I found I had to be rather defensive about that." Well, yes, between naivety and apparent naivety there's an entire ocean, an ocean in which you could wave or drown. And, in the battle between waving and drowning, the critics have seized on the titles of Hodgkin's paintings – titles, incidentally, reminiscent of Stevie Smith or another apparently naive poet, e e cummings – as ammunition. See, say the critics who want to make the arguments for complexity and richness, here are these titles (Waking up in Naples, In a French Restaurant, In Paris With You) which show that behind the wild splashes of colour are real events, real memories, real narratives. See, say the critics who want to make the argument for naivety, here are these titles which bear no relation to these paintings. They're the painterly equivalent of flirtation. They offer more than they deliver.

So the critics who want to argue for complexity want to know the stories, because how can you understand a painting if you don't know the story behind it? But what, in the end, has a story got to do with a painting? A painting, surely, is like a poem. It's an experience which undergoes a long, painstaking, often painful process of transformation – alchemy if you like – to become something else. The story behind it might be interesting to a biographer, or a voyeur, or an art critic, but it's ultimately irrelevant because it's a different thing. Isn't it? "Yes," says Hodgkin, "it's something totally different."

And then, amazingly, perversely, he asks Andy to dig out one of his earliest pictures and tells me the story behind it. It's called Memoirs. It was painted in 1949 when he was 17, during a summer on Long Island, when he was staying with one of his mother's friends. The friend is lying on a couch, telling him stories and he is gazing, with a beady eye, back. Hodgkin has talked a great deal, over the years, about the "incurable pain" of creation. Was it, even at 17, painful to produce? "Oh yes," he says. The boy who decided at seven that he was going to be an artist always knew, he says, that art would be about pain.

There was pain of a different kind later, when he married, knowing he was gay, and taught, to support his children, knowing that he was on this planet to make art, and then when he left his wife and family to follow his sexual inclinations, and his heart. Now, he is as near to art establishment as you can get and has been with the man he loves, the music writer Antony Peattie, for 20 years, but there is, it's clear from the sorrow etched deep in his face, and the tears that well up at intervals, still pain.

But there's pleasure, too. A potential source of it is the first large-scale exhibition of his prints, organised by the Barbican Art Gallery, at the PM Gallery in Ealing. The gallery is the extension to Pitzhanger Manor, an elegant 18th-century house designed by Sir John Soane, a man Hodgkin regards as "a great unsung hero". Its restrained domestic interiors seem like the perfect foil to his vibrant splashes of colour, surrounded, as they are, by trees and park. I didn't realise, until I saw them, that prints could be so multi-layered, so alive. Here are the palm trees that feature so prominently in his paintings. Here are the proscenia that act as extra frames between the work and the world. Here are the vast sweeps, the gentle layers, and curves. It was, perhaps, unlikely that an artist who can take many years to produce a single painting would be happy with the single roll of a litho press. Instead, after years of experimentation, he has hit on a complex and painstaking combination of techniques to produce the richness he seeks. And it works – my God, it works.

Can he look on it with pride? Surely he can look on this with pride?

Hodgkin's face crumples up again. "No," he says. "I had a great friend, a painter called Patrick Caulfied. I remember going round an exhibition of his, a retrospective. He was crying," says Hodgkin, who is also crying. "He just kept saying 'not enough, not enough'."

But then he shows me some of his recent pictures. They are restrained – sometimes just a few brushstrokes on bare wood. They are confident. They are amazing. Among them is a painting which, says Hodgkin, could be an illustration to the Larkin poem. It's called And the Skies Are Not Cloudy All Day. I'm tempted to say that the title says it all, but actually the picture says much, much more.

Howard Hodgkin: Prints, from tomorrow at the PM Gallery, London W5, to 28 February (www.ealing.gov.uk/pmgalleryandhouse)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments