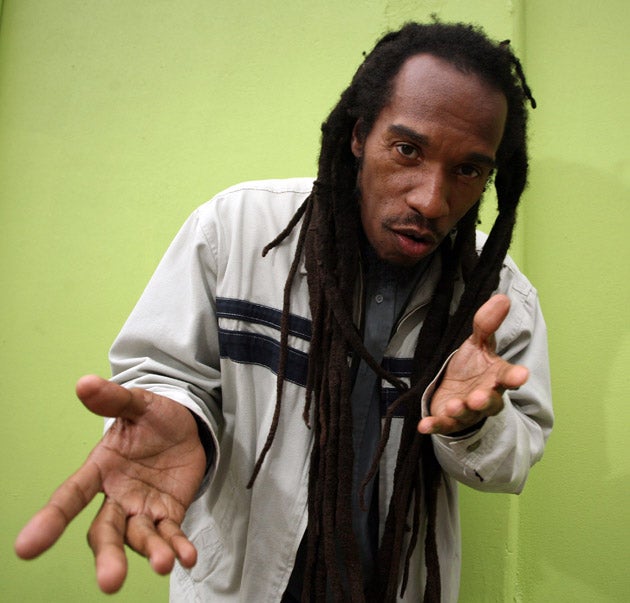

Benjamin Zephaniah: 'I'm just a normal bloke who writes poems'

He survived a turbulent upbringing and stints in prison to become one of Britain's best-loved poets – now Benjamin Zephaniah wants to find his soul mate

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Iwas beginning to believe," says Benjamin Zephaniah, "that I was a mindless drugs freak". He looks pained as he says it, but this isn't a confession. Squashed between the telly and the sofa in Arthur Smith's front room, he's performing his poem "Rong Radio". Upstairs, the comedian Stephen K Amos has been doing a skit in the bath. Musicians have been playing in the bedroom and we, the tiny "studio" audience for this recording of Smith's Radio 4 show, Arthur Smith's Balham Bash, have been wandering from room to room, occasionally returning to the kitchen to grab fistfuls of tortilla chips. "So, was that your smallest ever venue for a performance?" I ask Zephaniah when the microphones are switched off. "Oh no," he says. "I was once asked to do one in this woman's home, just in front of her two kids. They sort of became friends."

I can "sort of" imagine, because everyone, it soon becomes clear, wants to be Benjamin Zephaniah's friend. A nice lady from the BBC asks him, in tones that imply he might not have heard of it, if he ever listens to Radio 4. A producer from BBC7 raves about a play he once wrote about a hurricane. A young black man in baggy jeans shakes his hand. And Stephen K Amos, who has just had us all in stitches with his account of meeting Prince Philip at Buckingham Palace, tells Zephaniah that a performance of his, many years ago, changed his life.

"I can vaguely remember that evening," says Zephaniah, when I've managed to wrest him away from the adoring audience, and into a café in Balham High Street, "and for him it was a turning point in his life. I get that almost every day. It can be some minor poem in a book and I'll think, 'I wrote that when I was on the toilet'. It's strange because I think I'm just a normal bloke writing poems."

Well, Benjamin Zephaniah may or may not be a "normal bloke", but most blokes who write poems do not get their names put forward for Oxford Professor of Poetry, or Poet Laureate, or get 13 honorary degrees, or get invited to meet Nelson Mandela, or get asked by prime ministers to help with education policy or do worldwide sell-out tours, or get offered, and turn down, OBEs, or write best-selling novels for children, or get stopped, every two minutes, on Balham High Street. Most "blokes who write poems" don't get recognised, ever. And most "blokes who write poems" don't go on the telly, or the radio, or get their interviews interrupted, every few sentences, by cheery smiles and waves and nods and cheery cries of, "thanks, mate!"

But then this "angry, illiterate, uneducated, ex-hustler, rebellious Rastafarian" (which is how Zephaniah describes himself in the foreword to his poetry collection, Too Black, Too Strong) is not like "most blokes who write poems". For a start, he left school at 13, barely able to read or write. He still has trouble writing now, manages with computer spell-checks, his own private code and (until she left to go back to India) a miracle-working secretary. He writes his poems in his head, knows when something works because "something sticks", he says, "and it won't leave me". Some, it has to be said, work better than others. Some, on the page, tend towards the crudely propagandist and the chopped-up prose, but some are extremely touching, and many are shot through with great energy and wit. And all of them are lifted by Zephaniah's extraordinary gifts as a performer, his passion, his bounce, his soothing Brummie-meets-patois tones, and his gap-toothed charm.

It all started, like so much else, with his mother. Having, according to his poem "Naked", "read a poster on a/ hot tin street in Jamaica that told her/ that Britain loves her", she came to Handsworth, where she worked as a nurse and married a postman from Barbados. If Britain loved her, however, her husband didn't – or at least not enough to stop hitting her. "I remember," says Zephaniah, "saying to a kid one day, 'what do you do when your dad beats your mum?' I just thought it was normal." When he was eight, his mother left the family home with Benjamin, leaving his brothers and sisters with his father. What he remembers from those days, he says, is moving, under false names, from one boarding house to another. Once, when his father tracked her down, and beat her, he tried to protect her. "I had a little knife," he says, "and I was trying to get at his vein, and the police came and arrested me." A little knife? How old was he? "Oh, Christina, I'm not very good with dates. I must have been about nine or ten."

It was his first "trouble with the police", but certainly not his last. By the time he was 13, he had been expelled from school. In his children's novel Gangsta Rap he describes the extraordinary facilities – recording studios, tailored coaching, etc. – made available to a trio of teenagers excluded from school, facilities that enable them to launch careers as best-selling rappers. It wasn't, I presume, quite like that for him. "No," says Zephaniah, taking a huge bite of falafel, "they just left us in the streets, so you had to fend for yourself." And the streets, perhaps inevitably, led to petty, and then not-so-petty crime, borstal and then jail. Some of my Caribbean friends, I tell him, were "sorted out", in similar circumstances, by terrifying, matriarchal mums. Did his try?

Zephaniah chews on his falafel and thinks for a moment. "It's interesting," he says finally. "My mother didn't talk to me. She's not – gosh can I say this? – she just didn't have the emotional intelligence. She disciplined and warned me – she didn't really kick me around – but she was so busy trying to hold herself together. You know what she would do?" he muses. "If she wanted to make a point, she would tell me a story about it." When he was in borstal, she would travel miles, without a car, to see him. "She never gave me a great big lecture. She would just tell me these stories."

At home, or in whatever room was currently home, the only book was the Bible, but there were his mother's stories, and also the Jamaican poems ("Anancy stories, a bit of reggae and ska, dialect poets, that sort of thing") she used to recite, that she'd learnt at school. "When I was eight years old, I knew I wanted to be a poet," he confides. "I had this idea of going from community centre to community centre." He made his first public performance in church when he was ten, but it was when he was 22, working in a bookshop co-operative, that he realised that he was already earning a living from poetry, and it was time to "take the plunge". "I really don't like it when people talk about my career," he says. "I just concentrated on the poetry. I wanted to move people. I wanted to get people thinking. If people stopped listening to my poetry tomorrow, and nobody bought my books, I'd still want to write poems."

When he started, he was something of a lone voice. "I remember," he says, "seeing Linton Kwesi Johnson on the television and going, 'wow, there's somebody like me out there'." Like Johnson, he spoke out on behalf of the immigrants, and children of immigrants, who were treated as second-class citizens, but he also spoke out for the wider poor and dispossessed, for victims of oppression and colonialism everywhere and (he's a passionate vegan) for animals. If the messages of his poems – and yes, he does believe that poems should have messages – were sometimes a little simplistic, they were redeemed by their wit. Zephaniah, who has been quoted as saying that he's not just "not intellectual" but "not that intelligent", wouldn't claim to be a sophisticated political thinker. He's an activist, a polemicist, evangelical about his causes, evangelical about the power of poetry.

For nearly 30 years now, he has travelled the world, performing his poems and his music (his latest album, Naked, is a mixture of jazz, reggae, hip-hop and house), campaigning and writing books. Over a 22-day period in 1991, he performed on every continent on the planet. Although he has been based largely in the East End of London, he has spent periods living in Egypt (a family in Aswan invited him to live with them, so he did) and in the former Yugoslavia, where he had a No. 1 hit. "I was a millionaire there," he tells me with a grin, "but you couldn't take the money out. I used to live like a king. I used to hire helicopters!" And now he spends at least half the year in Beijing. "I love martial arts," he explains, "and it's a great place for clubbing. When you go into the villages, it's another world. They've got mountains, they've got forests. I've just got this thing about seeing as much as I can before I die."

What he doesn't mention is a domestic life – because he doesn't have one. He was married for 12 years to Amina, a theatre administrator, but she left him eight years ago and broke his heart. "I didn't really see the reason for it," he says matter-of-factly. Once, he confides, when a woman in a night club bought him a drink, he had "a panic attack" and ran away. "I thought she could fall in love with me, I could fall in love with her. I just disappeared." He is also, he discovered some years ago, infertile, and has written movingly about "a life full of lonely, childless eternities/ where only poetry gives me life".

Three years ago, he moved to a small village in Lincolnshire. Metropolitan liberal lefties, and some black friends, are aghast, but he has "always wanted to live in a nice little quaint English village" and likes the clean air. "The thing is," he says, "I felt really lonely in London, and I thought, well, I might as well go somewhere where I can enjoy being on my own." His mother, who he speaks to every day, is at least pleased that he's living in a bungalow. It "seriously bothers her", he says, that he's on his own, that he might die and nobody find him. "She goes, 'oh great, no stairs,'" he says with a rueful smile. "She's worried about me falling down the stairs."

Benjamin Zephaniah is not worried about the stairs. He's worried about running out of time. And he's worried, he admits, about growing old alone. "I just want to keep doing what I do. I want to write better books, I want to play better music. I suppose," says this good-hearted, passionate and strangely childlike man, "I do want to find my soulmate, but in terms of what I do, I remember that most people are doing jobs that they don't like. I never take that for granted. I never take that for granted at all."

Benjamin Zephaniah is a mentor for the Poetry Society's SLAMbassadors programme (www.poetrysociety.org.uk). He will be performing at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on 10 July (www. southbankcentre.co.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments