The Wind Rises, film review: One of Miyazaki's most beautiful but puzzling movies

A suitably rich and strange exit for one of the giants of Japanese cinema

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

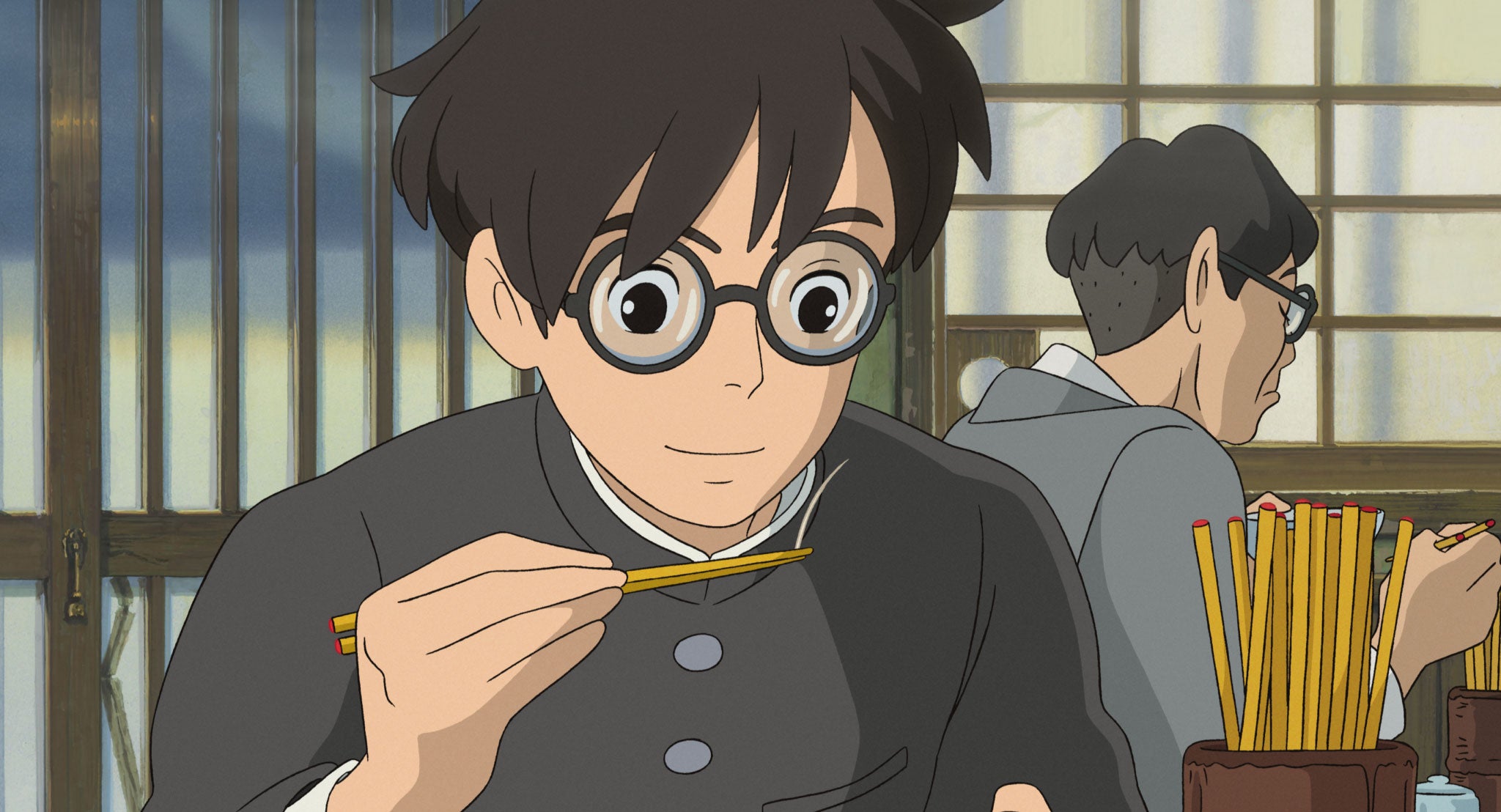

Your support makes all the difference.The Wind Rises is said to be the “farewell” animated feature from the Japanese master Hayao Miyazaki, who is now in his 70s. It is one of his most beautiful but puzzling films – a partly fictionalised biopic of a young Japanese aircraft designer in the run-up to the Second World War.

Miyazaki’s film is, variously, a romance, a film about aeronautical engineering, a study of militarism, a chronicle of illness and natural disaster, and a very poetic meditation on the nature of creativity.

We are used to Miyazaki directing somewhat cutesy films about gold fish (Ponyo) or the growing pains of little girls (Spirited Away). The Wind Rises is in a very different register and seems aimed at a far older audience.

It has an extraordinary grace and delicacy – a subtlety that you’ll never encounter in the latest CGI Hollywood animated feature. Miyazaki is dealing with bereavement and death. He is also making continual reference to the “kingdom of dreams”. A beguiling, mournful score by Joe Hisaishi adds to the haunting nature of a story always reminding us of the evanescence of life.

The director is utterly unapologetic about blurring fantasy and realist elements. “Dreams are convenient. One can go anywhere,” a character remarks early on.

Miyazaki’s main protagonist is Jiro Horikoshi, a real-life Japanese engineer who worked at Mitsubishi and eventually designed the Zero plane, a fighter used by the Japanese Navy. His inspiration and mentor is the great Italian aircraft designer, Count Gianni Caproni, a flamboyant figure with a bowler hat and twirling moustache.

Whether Jiro and Caproni met in real life isn’t an issue for the film-makers. They were kindred spirits and are shown as forming a firm bond… in Jiro’s reveries. The Italian is the sorcerer. The Japanese boy is his apprentice. In real life, it is impossible to walk along the wings of a plane in mid-flight to examine its aerodynamics. In the dream sequences here, such behaviour is perfectly natural.

Airplanes, the two inventors agree, are not for making war or for generating huge profits. They are themselves “beautiful dreams”. Taking their inspiration from paper kites, fish bones and streamlined architecture, Caproni in Italy and Jiro in Japan design lightweight and remarkably graceful planes that swoop and soar through the air.

Both men’s inventions were used in warfare. Miyazaki doesn’t ignore this fact but he doesn’t foreground it either. One of the most troubling aspects to The Wind Rises is its equivocal attitude toward the destructive uses to which the planes were put. There is imagery of bombing. We know that Jiro and his colleagues are designing for the Imperial Navy. Nonetheless, Miyazaki portrays him as a sweet-natured, innocent visionary, untouched by the brutal ideology of the Japanese military machine. His character is remarkably similar to that of Leslie Howard’s RJ Mitchell, inventor of the Spitfire, in the British wartime film The First of the Few (1942). He is an idealist and a dreamer.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

It is tempting to see autobiographical elements in the film. Just like Miyazaki himself, Jiro spends hours drawing. Like the animator, he is an individual artist working with a huge team on projects that combine both handcrafted and industrial elements.

Early on in the film, when he is still a boy, Jiro is caught in a huge Kanto earthquake of 1923. Miyazaki and his animators portray the disaster in bravura fashion. The earth itself is shown shifting and rippling. Houses bend and buckle. Huge crowds spill off a train. In the chaos, Jiro is heroic, rescuing a woman whose leg is broken. The earthquake takes place just after he first meets the beautiful Nahoko, who remembers him as vividly as he remembers her. She makes an impression on him by rescuing his hat as it blows away in the wind. Years later, he repays the favour by grabbing her parasol during a storm.

Much of the film is set in a period of unrest and deprivation in Japan. There are strange scenes in which Jiro learns of the poverty in which so many of his fellow citizens live as he meets starving kids on the streets. Jiro, though, isn’t remotely interested in politics or history. His twin obsessions are Nahoko, whom he wants to marry, and his quest to design the perfect plane. He courts her by throwing a paper plane in her direction. She, in turn, inspires him.

Certain resonances here may be lost on non-Japanese audiences or those without a specialist knowledge of Japanese social history between the wars. Miyazaki, though, has always been the most outward-looking of film-makers – it is one of the reasons why his films are cherished by everyone from Pixar’s John Lasseter to the creators of The Simpsons.

He cites the western authors Rosemary Sutcliff, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and Ursula K Le Guin among his influences. His admiration of the French animated classic The King and the Mocking Bird, which was recently re-released, is also well chronicled.

The Wind Rises may seem like quintessentially Japanese subject matter but it also includes explicit references to Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. (There is a prolonged sequence in a sanatorium.) Its title comes from lines written by Paul Valéry. (“The wind is rising – we must try to live.”) The portrait here of romance amid illness and death is reminiscent of the type of lyrical, fatalistic melodramas that Marcel Carné used to make from Jacques Prévert screenplays in the 1940s.

The film is being released in the UK in two versions: the original with subtitles and an English-language dub voiced by Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Emily Blunt and others.

Given the poetic language, the subtitled option is surely the best. In either version, The Wind Rises has its share of perplexing moments and scenes in which the narrative drifts. It is, though, a film of startling formal beauty.

If The Wind Rises is Miyazaki’s final feature, it marks a suitably rich and strange exit for one of the giants of Japanese cinema.

Hayao Miyazaki, 126 mins. Featuring voices of: Hideaki Anno, Miori Takimoto.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments