MLK/FBI review: A smart, incisive account of the darkest chapter in FBI history

Pollard carefully collates contemporary footage that best expresses the heart of this moral assault, offering a necessary dose of context

Dir: Sam Pollard. 15, 104 mins

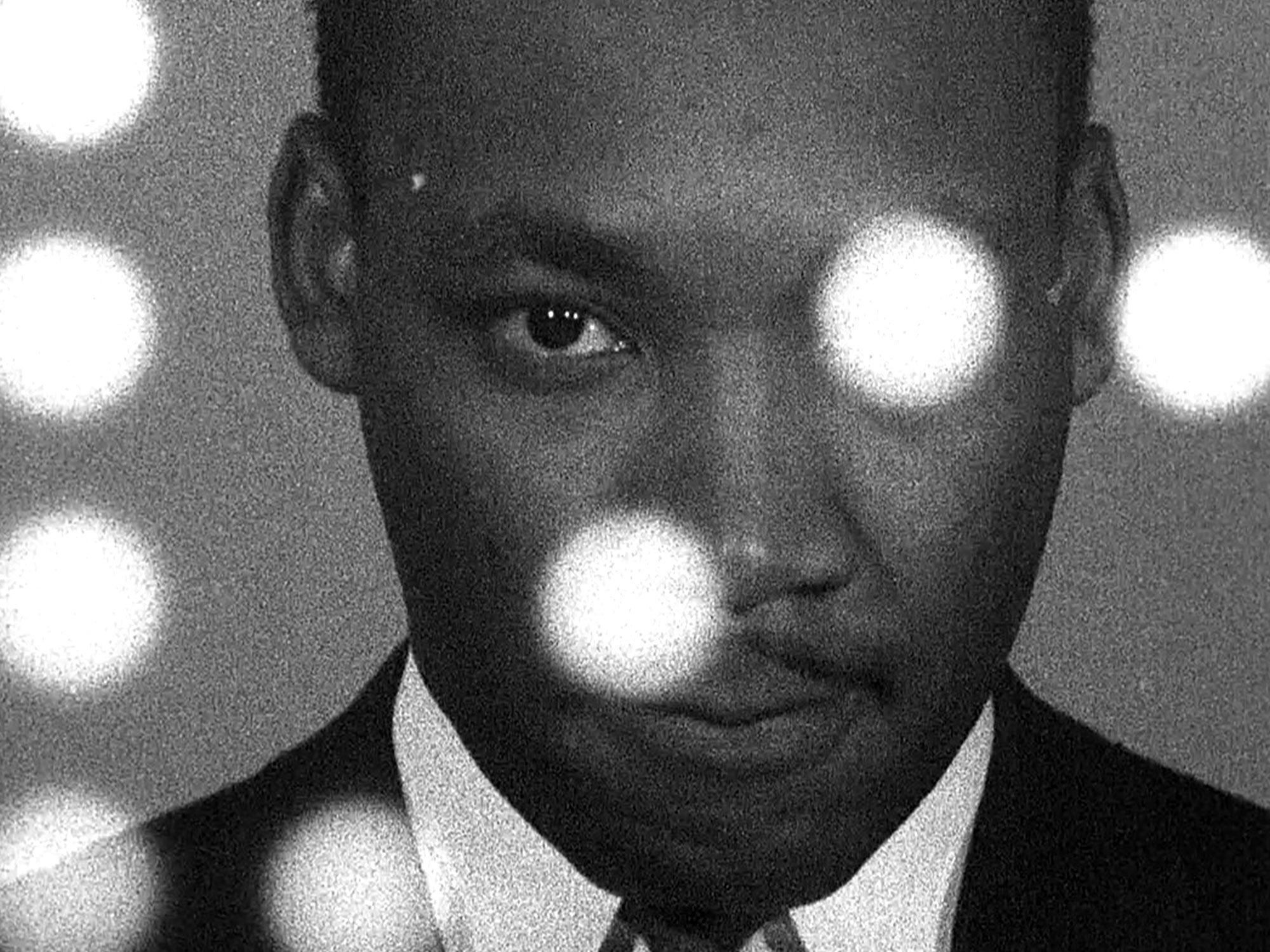

Sam Pollard’s MLK/FBI, a documentary covering the US government’s surveillance and harassment of Martin Luther King, Jr, holds off on its most damning indictment until the very end. The point made is that FBI Director J Edgar Hoover’s resentment towards the civil rights leader wasn’t just personal animosity. As author David J Garrow points out: “The FBI was not a renegade agency. It was fundamentally a part of the existing mainstream political order.” This was the will of white America.

When Hoover attacked King, shortly after he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, and called him the “most notorious liar”, a survey of Americans saw 50 per cent of them side with the aggressor. What Pollard offers is a necessary dose of context to what former FBI Director James Comey calls, “the darkest part of the Bureau’s history”.

After the March on Washington in 1963, where King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, William C Sullivan, head of FBI domestic intelligence, singled out the Baptist minister as a threat and wrote that “we must use every resource at our disposal to destroy him”. His calls were tapped, as the agency shielded itself behind concerns about his association with Stanley Levison, a white Jewish lawyer with supposed ties to the Communist Party.

The fact they happened to capture evidence of King allegedly conducting extramarital affairs was incidental. But it sparked an obsession – the FBI tracked his movements, made note of who visited him, and bugged his hotel rooms. It culminated in a hand-written note, bundled in with a recording of King’s alleged indiscretions, in which an agent posing as a disgruntled fan told the civil rights leader to kill himself. As MLK/FBI makes clear, Hoover’s obsession with King’s private affairs stemmed directly from the white supremacist narrative that a Black man’s sexuality is something inherently dangerous and perverse.

Pollard earned an Oscar nomination for editing Spike’s Lee’s 4 Little Girls, a deeply affecting documentary on the 1963 bombing of an Alabama Baptist church by the Ku Klux Klan. Here, working with editor Laura Tomaselli, he carefully collates contemporary footage that best expresses the heart of this moral assault. We see and hear King’s speeches, still as beautiful and impassioned today, as well as his television appearances.

We also see what King was up against – the propaganda of the white establishment. Newsreels fawn over President Lyndon B Johnson and Hollywood movies such as Walk a Crooked Mile and The FBI Story make heroes out of Hoover’s “G-men”, short for “Government man”. Pollard only reveals the faces of his interviewees at the very end, so that their disembodied voices can sound like they’re in conversation with each other. Those who were by King’s side, like Clarence B Jones and Andrew Young, provide the eyewitness accounts. Historians and writers, such as Garrow and Donna Murch, fill in the gaps.

MLK/FBI is a historically rigid account that also examines how the FBI’s actions have (or haven’t) impacted King’s wider legacy. There’s a carefully, and commendably, handled section on the hand-written notation in his FBI file, where Sullivan added the dubious allegation that he was present during the rape of a female parishioner. Though the transcripts have been declassified, the tapes themselves won’t be made public until 2027. There’s no doubt someone else will make a documentary on them, but Pollard’s smart, incisive film asks an important question: do we even have a right to these recordings? Or by studying them, do we simply further the goals of decades-old, anti-Black propaganda?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies