Is Anybody There? (12A)

Still got the magic touch

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The convergence of discomforted old age and disaffected youth is a theme that's given the cinema some fine moments: Cinema Paradiso, Apt Pupil, Harold and Maude, Venus. The films all strayed too close to the hard rock of mortality for comfort, but often managed to wring some bittersweet comedy from the behaviour of juvenile elders and prematurely grave kids.

John Crowley's Is Anybody There? is in a direct line of descent from them. It's set in 1987 in an unnamed English seaside town where the home of young Edward (Bill Milner) doubles as a twilight home run by his parents (Anne-Marie Duff and David Morrissey, all but unrecognisable in a hideous Paul Calf hairstyle). The film opens, with breezy confidence, in the middle of Christmas lunch, where Bill's family share the table, the turkey and crackers with the inmates – a fine job-lot of British character legends from bygone days.

Leslie Phillips as Reg, a boozing philanderer, smirks and intones off-colour limericks into the child's ear. Elizabeth Spriggs (who died while the film was in post-production) sits resplendent in a tent-sized dress, putting bits of dinner in her hair. Peter Vaughn, who appears contractually obliged to appear in any film about the over-seventies, twitches with Parkinson's disease as a shell-shocked war veteran. Sylvia Syms, last seen playing the Queen Mum in The Queen, grumbles about everything. Rosemary Harris, despite her prosthetic leg, tries to appear alluring to the tippling lothario, without success.

Horrified by their drooling eccentricity, young Edward has developed an obsession with death. His excitement on learning that an inmate is shortly to join the choir invisible isn't just glee at their departure. He wants to understand death, inspect it at close quarters, find out where people go and how they exist there. He puts a tape-recorder under inmates' deathbeds, to record the sound of their escaping spirit.

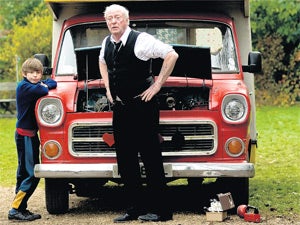

One day, Edward is listening to the hiss of death on headphones when he's nearly run over by an old van whose side panels advertise a magician: the Amazing Clarence. The eponymous Clarence turns out to be a once-famous prestidigitator who, with his glamorous assistant, used to knock 'em dead on the supper party circuit. Clarence has been sent to Lark Hall by the town's social services, and he hates the place. He surveys his fellow inmates with horror. He learns that his predecessor in the room died in his bed. When Edward chats to him, he's told to bugger off.

Michael Caine, as Clarence, has played elderly men before (notably in Last Orders) and never puts a foot wrong: his shaggy chin, his rheumy eyes, his loud, abrupt delivery all suggest a melancholy, independent figure sliding towards the grave and determined not to slide too quickly. There's a nicely poignant moment when he gazes at the dismal walls of Lark Hall and says, pleadingly, to Anne-Marie Duff, "You realise this is... only temporary?"

You know the death-haunted child and the life-force-embodying vieillard are bound to become buddies, but the director Crowley doesn't make their friendship too easily achieved. Edward saves Clarence's life when the despairing magician turns his van into a carbon monoxide facility, but, in hospital afterwards, he remains an irascible old git, unimpressed by Edward's fondness for the paranormal. Since illusion comes naturally to him, he conducts an amusingly fake séance in the family cellar. But Clarence is himself haunted by the knowledge that the dead will never come back – like his wife (and magic assistant) who divorced him for the endless philandering, and died. We learn that the greatest regret in Clarence's life is that he could never find her grave, to ask her forgiveness.

As their friendship flourishes, the old man and the boy help each other out. Clarence arranges to put on a magic show at Edward's birthday party, where a trick goes disastrously wrong and there's blood all over the living room. Meanwhile, Edward's parents seem to be about to go the same way as Clarence and his wife, after Edward accidentally tape-records his father confessing to 18-year-old Tanya his crush on her, and Edward plays the incriminating protestations to his mother in the midst of a furious rant about his neglect.

After this emotional sturm und drang, Edward runs off with an increasingly confused Clarence to find a graveyard where... but I'll spare you the details, except to say the climax is unsentimental, but intensely satisfying. It allows Anne-Marie Duff to give the old magician an illusion of redemption in the back of a car that sent a large tear rolling down my cheek.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

It's the little details that lift Crowley's film from black humour into something warmer. Such as Edward's kindly meant gesture in pushing under Clarence's door some helpful brochures on coping with bereavement and the like: they include one about the efficacy of cervical smear tests. The clothes are spot-on, like the terrible denim flying-jacket David Morrissey wears to impress the sexy live-in nurse, Tanya. The production designers have done a fine job on the look of the house, the rooms and mirrors and curtains – a drab, dispiriting, horribly recognisable place that would have inspired Philip Larkin to melancholy rapture. And I loved the birthday party scene, in which 11-year-olds and senile octogenarians play musical statues and dance together to "Come on Eileen"; when one boy tells the Parkinson-sufferer Bob, "You moved!" the reply comes, "I ain't stopped movin' since 1917..."

Among some first-class performances, Bill Milner brings a bright-eyed disgust, and a convincing regional accent, to the role of Edward, while Anne-Marie Duff, as his mother, luminously conveys long-suffering resilience and a natural kindness behind her brisk exterior. You can imagine her setting up a retirement home for reasons other than the financial. She's the warm heart of this intelligently-written, smartly-handled study of laughter in the dark.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments