First Night: We Need To Talk About Kevin, Cannes Film Festival

An eerie adaptation that doesn't quite ring true

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It's been nine years since the British director Lynne Ramsay helmed Morvern Callar, and her return to the screen is a challenging affair. In an extraordinary opening sequence, reminiscent of a Chapman Brothers sculpture, a group of bodies huddled together in a sea of red paint pass Eva over their heads before submerging her. It's a powerful metaphor for a mother being condemned for the actions of her son.

While the Lionel Shriver novel concentrates on a series of letters written after Kevin has massacred his classmates in a Columbine-style shooting, the movie adaptation purposely disorients the viewer by flitting through past and present. Ramsay cleverly structures her first act so that it doesn't matter whether the audience has prior knowledge of the school shooting or not. It's clear that something bad has happened and the crux is whether Eva should have done more to prevent Kevin going off the rails, given that he has always acted like Damien from The Omen. The iconography of a horror film is omnipresent.

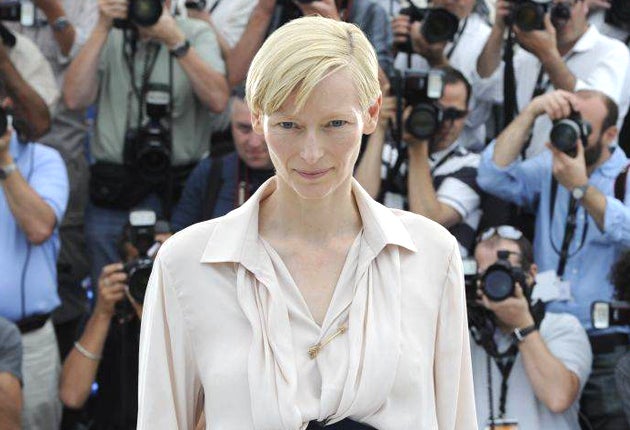

For the most part, though, the central relationship between Tilda Swinton's tormented mother and her ogre of a son is clunky. Swinton's subtle performance depicts Eva as a frustrated and unhappy mother. In one pointed moment she stands with her crying baby next to a pneumatic drill plugging away at the streets of New York.

She is guilt-ridden yet the emotion never properly resonates because she is playing against a one-dimensional Kevin. Whether being played as a child by Jasper Newell or as a teenager by Ezra Miller, he is menacing but unbelievable. The dialogue between the two is stilted. Even the book's famous masturbation sequence, in which Kevin ignores his watching mother, fails to hit home.

John C Reilly is wasted in the role of Kevin's father, Franklin, appearing sporadically as a glorified cheerleader who is trying hard to support mother and son. As a result the "shock" ending has far less impact.

It's testament to the Ratcatcher director that there is still much to admire here. Ramsay is a master of metaphor, capturing Eva's feelings of helplessness and isolation. An amusing scene in a supermarket sees Eva standing like a screen test against a Warhol-esque wall of tomato soup cans. It's a moment that ties in with Kevin's later rebuke to the audience in which he asserts that television viewers are "watching people like me. Don't you think they would have changed channel if all I did was get an A in geography?"

Cannes has a record of championing films about American school shootings, from Gus Van Sant's Palme d'Or winner, Elephant, to Michael Moore's Bowling For Columbine. Ramsay's pleasing aesthetic and hard-hitting subject matter may yet impress the jury.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments