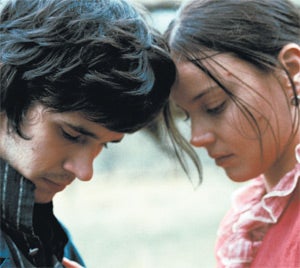

Bright Star (PG)

A thing of beauty in itself

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jane Campion's film Bright Star is a wistful and melancholic account of the unconsummated romance between the poet John Keats and his neighbour Fanny Brawne. It's poetic, too, though not in any precious, Fotherington-Tomas sort of way.

Campion seems to understand that Keats's poetry can take care of itself, and scatters it about in fragments though the story; the poetry of her film lies in visual rather than verbal beauty, a matter of swooning close-ups and sudden starbursts of colour, of light through a window or a butterfly resting on a doorknob.

Bright Star begins in 1818, three years before Keats was to die in Italy, aged 25, impecunious and critically unregarded. The film doesn't wail over this neglect – posterity has been the best corrective – but tries to situate him in his life and time. It investigates the peculiar ménage that brought the poet into contact with a young woman he first admires, then teaches, then falls in love with. Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish), spirited and self-possessed, lives with her widowed mother, sister and brother in one half of a Hampstead cottage. A dab hand at stitching, Fanny makes "a triple-pleated mushroom collar" for her dress and wears racy bonnets with elongated crowns, but she's not sure she understands the poems written by that pale gent Keats (Ben Whishaw) who lives in the cottage's other half. She dispatches her sister Toots (Edie Martin) to the bookseller for a copy of his poem Endymion, "to see if he's an idiot or not".

Fanny is intrigued, and wants to learn more, though first she has to get past the flatmate. This would be Charles Brown (Paul Schneider), an oafish poet who guards Keats like a jealous wife and regards Fanny as a destructive intruder; their antagonism spits and boils the length of the film. The other stumbling block to romance is the conventional one of money – the otherwise indulgent Mrs Brawne (Kerry Fox) is unwilling to see her older daughter abandon herself to a man who has "no living and no income". Yet even the mother comes round to Keats, who earns his place as a family guest at Christmas by being jolly and cutting a caper in front of the fire. When they ask him to recite a poem he gamely begins, "When I have fears that I may cease to be", before halting after six lines and sheepishly admitting that his mind's "gone blank". This is a nice subtlety in Campion's script, because the poet knows he is coming to the line, "I shall never look upon thee more", and was perhaps reminded of his brother Tom, then close to dying.

Yet it is his own mortality that dominates the later parts of the film. Though it makes no mention of his time as a medical student, Keats knew he was dying of tuberculosis from the colour of blood he coughed up on his pillow. It's this awareness that lends such poignancy to his romance with Fanny, who at least senses that their time together is not long. To underscore this mood Campion, rather than quoting great reams of the poetry, invests scenes with a restrained lyrical fervour. While Keats is away travelling, Fanny turns her bedroom into a hothouse for butterflies, eloquent enough of life's transience and fragility. Out of doors, the picture of Hampstead, then still a village on the outskirts of London, is a half-genteel, half-workaday neighbourhood, its gardens flapping with washing and geese. Then a stroll suddenly takes Fanny into a field of bluebells, which might not be as clever as a poem but still brims with loveliness.

The film also depends for its power on Cornish, an Australian actress whose dark-eyed gaze seems to contain more feeling than she knows what to do with. In the early scenes Fanny is flighty and dressy – Keats calls her "minxstress" – more certain of her charm than of her capability; only as her commitment to him deepens do we see a more complex and volatile woman. When the post brings only a short letter from Keats, she gives way to histrionics and says she wants "to kill herself", but her persistence finally wins the approval of her mother in their engagement. Towards the end, Cornish comes through very strongly indeed. On Whishaw, I'm undecided; when I first saw the film he seemed weedy and withdrawn. It was hard to imagine where Keats had summoned the energy to write so much in his last five years. A second viewing slightly altered my view – he is still listless, but his brooding and twitchiness now seem affecting in the face of his brother's death and his own sorrowful decline. "A poet is not at all poetical," he says to Fanny, and I wish Campion had pushed that idea a little further and made his vulnerability perhaps more comic, or tragicomic. (The great last lines of his final letter: "I can scarcely bid you good bye even in a letter. I always made an awkward bow.")

Yet when you consider the pitfalls of making a film about a poet, you have to doff your stovepipe hat to Campion: there are no thousand-yard stares as the verses boom in voiceover, no clunky lines à la, "You'll be the greatest poet of the 19th century, Keats!", and no silly links of poem to image. (Well, there is one, when he recites "Pillowed upon my fair love's ripening breast", and he's actually plonked his head on her breast.) Bright Star deals with the sonnets and the bonnets – top marks to the production and costume designer, Janet Patterson – with wit and restraint, and proves that a chaste romance needn't lack for passion, or poetry.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments