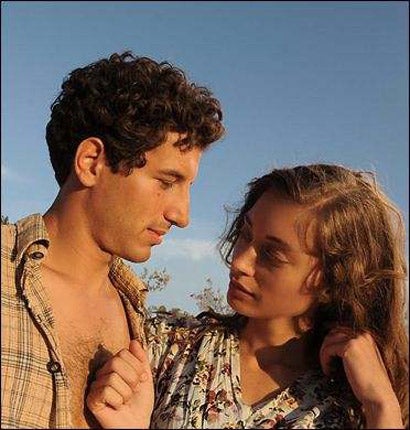

Baaria, Venice Film Festival

A poor relation to Paradiso

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This sprawling Sicilian family epic is certainly heartfelt. In its early scenes, it captures some of the same magic found in the director's best known work, Cinema Paradiso. Giuseppe Tornatore has a flair for capturing the child's-eye view of the world. The opening scenes, with their elaborate set-pieces and crowd scene, work the best. As he evokes the Palermo of the 1930s, the camera swoops around while Ennio Morricone music reverberates on the soundtrack. Every scene seems to have a huge army of extras. The storytelling style is operatic and – at least initially – massively enjoyable. Sadly, the longer the film lasts, the quicker the magic dissipates. Tornatore's formal mastery isn't matched by his knack for narrative. Individual scenes here are astounding, but the director doesn't always know how to link them.

This is the story of a tight-knit but impoverished Sicilian family. The father is a shepherd. Peppino is a mischievous kid. Food is scarce. Mussolini's blackshirts are on the streets. The peasants hate them and the landowners whose interests they serve. Gradually, we move through the Fascist era to the post-war period. Peppino (earnestly played by Francesco Scianna) may have only the most rudimentary education, but he has a burning sense of injustice. He becomes more and more involved in politics, joining the communist party and agitating for workers' rights. He marries his sweetheart and starts a family.

It's at this point that the film begins to sag. The seething scenes of old men gambling as kids play in the dust beside them, or shots of the austerely beautiful landscapes or sequences showing cinema-goers roaring at the screen during a silent projection, give way to a laborious family memoir.

We see more and more of Peppino's political struggles. Those astonishing crane and tracking shots give way to windy, self-righteous dialogue about political rights. Peppino grows irrevocably older and fathers more and more children. In one moving scene, he arrives home from his latest campaign just in time to see his ailing father for the last time.

Baaria is the first Italian film to open Venice in nearly 20 years; it is also one of the most expensive movies ever made in Italy. It is a full-blown epic in the tradition of old Italian cinema, and its producers clearly have high hopes that it can emulate the success of Cinema Paradiso. That would look to be a tall order. The film plays like a mini-series squashed into feature form.

The magnificence of much of the film-making only makes it all the more disappointing that the storytelling doesn't hang together better. Perhaps there is a political subtext here. Maybe Tornatore is evoking an era when Italians like Peppino were ready to stand up for their rights, whatever the sacrifice. The problem is that Baaria simply doesn't have the dramatic sweep to justify its inordinate running time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments