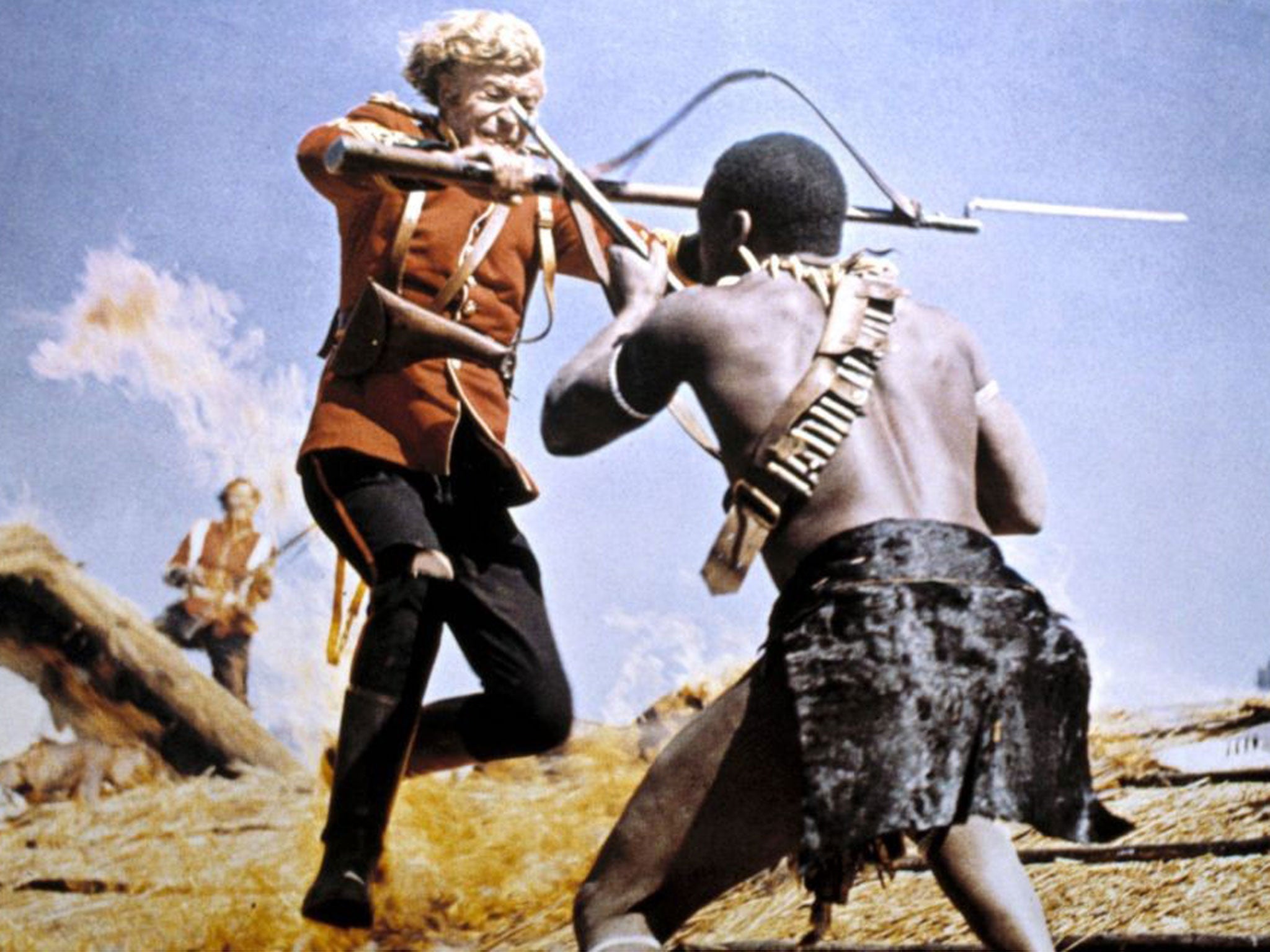

The untold story of the film Zulu starring Michael Caine, 50 years on

The Battle of Rorke’s Drift has entered British folklore thanks to the 1964 movie. But the story of the film is almost as remarkable as what it depicts. Sheldon Hall looks back

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This Wednesday marks a double anniversary. On 22 January 1879, at a remote mission station in Natal, South Africa, barely more than 100 British soldiers held off wave after wave of attacks by some 4,000 Zulu warriors. The Battle of Rorke’s Drift lasted 10 hours, from late afternoon till just before dawn the following morning. By the end of the fighting, 15 soldiers lay dead, with another two mortally wounded. Surrounding the camp were the bodies of 350 Zulus.

This makes for a remarkable tale of courage and tenacity, on both sides of the perimeter. But historically the battle was a minor incident which had little influence on the course of the Anglo-Zulu War. It might have remained a footnote in the history books or an anecdote told at regimental dinners had it not been for a film which dramatised the story and has kept it in the public mind ever since.

Premiered 85 years to the day after the event it commemorates, the film Zulu is 50 years’ old this week. On its initial release, in 1964, it was one of the biggest box-office hits of all time in the home market. For the next 12 years it remained in constant cinema circulation before making its first appearance on television. It has since become a Bank holiday television perennial, and remains beloved by the British public. But the story behind the film’s making is as unusual as the one that it tells.

The filmmakers

The principal artists responsible for Zulu were hardly Establishment figures. Screenwriter John Prebble was a former Communist Party member who had volunteered to fight in the Spanish Civil War. His co-writer, the American director Cy Endfield, had fled Hollywood in the early 1950s after he was named as a Communist during the McCarthyite witch-hunts. Endfield’s production partner and the film’s main star was Stanley Baker, a life-long supporter of the Labour Party.

All three were committed to progressive causes, but their motives in making Zulu were not political. It is not an anti-imperial diatribe any more than it is a celebration of colonial conquest. Its main purpose was frankly commercial, but Baker also saw the story as an chance to pay tribute to his Welsh homeland. This certainly explains the strong emphasis on the Welshness of the private soldiers – one of the many fictionalised elements of Zulu that have created a myth around the battle.

Filming under Apartheid

The producers had to keep their political views in check when they made the decision to shoot the film in South Africa, then in the grip of Apartheid. There were strict, legally enforced guidelines regarding the degree of freedom permitted to the cast and crew. It was impressed upon the 60-odd British visitors that sexual relations with people of other races would result in possible imprisonment, deportation or worse. Warned that miscegenation was a flogging offence, Baker is reported to have asked if he could have the lashes while doing it. The authorities were not amused.

The main filming location was in the spectacular Drakensberg Mountains in the Royal Natal National Park, a popular tourist spot distant from any large township. But a number of incidents brought home the realities of the oppressive regime. Chatting to John Marcus, one of several professional black stuntmen employed on the film, assistant editor Jennifer Bates invited him for a drink in the bar/canteen that had been built on site for the crew. Marcus pointed out that he was forbidden by law to mix socially with whites and could not enter.

In his autobiography, Michael Caine recalls an incident in which a black labourer was reprimanded by an Afrikaans foreman with a punch in the face. Baker sacked the foreman on the spot and made clear that such behaviour would not be tolerated. Caine swore never to make another film in South Africa while Apartheid was in force, and kept to his word.

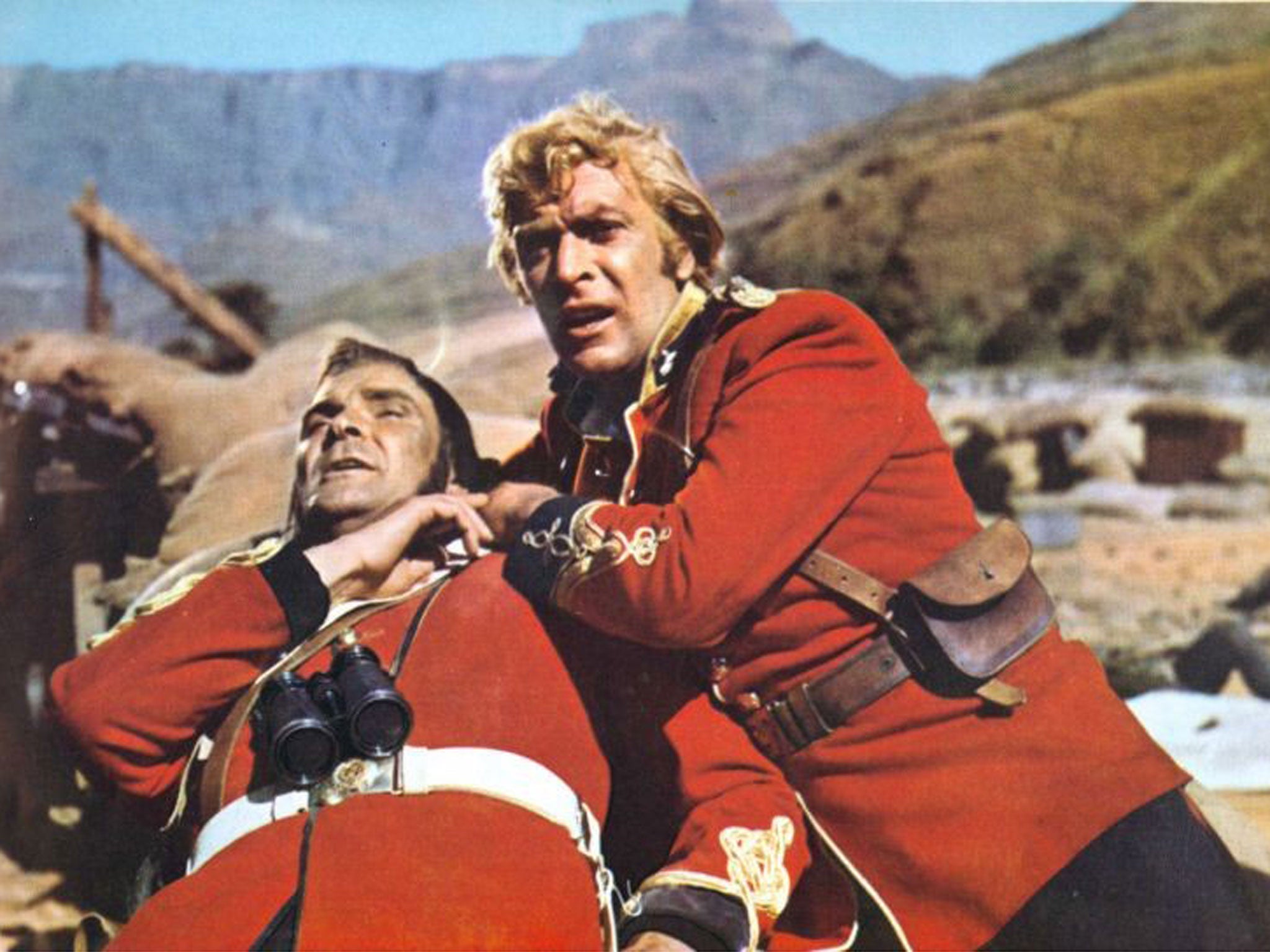

Introducing Michael Caine

Keeping watch over the tightly budgeted film was production supervisor Colin Lesslie. “I am very glad to be able to tell you,” he wrote at one point to the Embassy Pictures’ chief in London, “that in my opinion and from the little he has done so far, Michael Caine as ‘Bromhead’ is very good indeed. When he was cast for the part I couldn’t see it but I think (and hope) I was wrong.” This must have been a common reaction.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Not quite an unknown, the 30-year-old Caine was already making a name for himself on television but was becoming type-cast in working-class Cockney parts. Casting him as a blue-blooded officer in his first major film role represented a considerable risk, but it was one that paid off.

Alhough Caine has sometimes claimed that reviewers gave him a hard time, in fact almost every mention of him in press notices was favourable. Zulu brought him the attention which led to multi-film contracts and to top billing in his very next picture as Harry Palmer in The Ipcress File (1965).

Thousands of ’em?

Just as the soldiers were played by real soldiers – eighty national servicemen borrowed from the South African National Defence Force – so were most of the Zulus real Zulus. A mere 240 Zulu extras were employed for the battle scenes, bussed in from their tribal homes over 100 miles away. Around 1,000 additional tribesmen were filmed by the second unit in Zululand, but most of these scenes hit the cutting-room floor.

Living in remote rural areas, few if any Zulus had visited a cinema and television had not reached Natal. The crew rigged up a projector and outdoor screen, and the Zulus’ first sight of a motion picture was a Western. From then on, the “warriors” had a better idea of what they were being asked to do. Responsible for training and rehearsing them were stunt arrangers John Sullivan and Joe Powell. “The Zulus were initially suspicious of us in case we were taking the mickey,” says Powell, now 91. “After a couple of days they realised we weren’t and got into it. After that you couldn’t hold them back.”

Contrary to stories the Zulus were not paid with gifts of cattle or wristwatches but received wages in Rand. The main corps was paid the equivalent of nine shillings per day each, additional extras eight shillings, and the female dancers slightly less again. Associate producer Basil Keys remarked: “There is no equality of pay for women in the Zulu nation!”

Buthelezi’s tribute

For the opening sequence depicting a mass Zulu wedding, 600 additional background artists were brought in, including nightclub performers from Johannesburg, to play the principal dancers. During breaks in filming, they twisted and jived to modern pop records played over Tannoys, with director Cy Endfield among the crew members joining them.

The small but key role of King Cetshwayo was given to his direct descendant, the present-day Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi. The wedding dance was choreographed by Buthelezi’s mother, a tribal historian, and supervised by stuntman Simon Sabela, who later became South Africa’s first black film director. In July last year, accepting an award named after Sabela, Buthelezi dedicated it to “that epic production, which became a milestone event, not only in cinematic history, but within the Zulu nation.” He recalled that the cast “found themselves re-enacting the deeds of their own grandfathers. Somehow this drew the audience into what was, in the end, a very human experience.”

History and politics

Like all films, Zulu is of its time and captures the mood of its time more profoundly than is often realised. A conservative view would see it as a hymn to gung-ho heroism, to flag-waving patriotism and the glory days of the British Empire. In fact, by 1964 the sun was already setting on the empire and undoubtedly Zulu stirred a lot of nostalgia for it. For some, that explains its appeal.

But look again. The knowledge that colonialism was in its dying fall is there in the film. The script is filled with a sense that the soldiers are in a place they don’t belong and don’t want to be. The indigenous people are not disorganised savages but a disciplined army. And the young lieutenant, played by Caine, who had earlier dismissed the enemy as “fuzzies” and the levies on his own side as “cowardly blacks”, now declares himself ashamed at the “butcher’s yard” he has brought about.

A modern awareness of racial representation means that Zulu has undoubtedly “dated”. If the film were to be remade today, as internet rumours continually suggest, it would certainly be done differently. But the absence of individuated black characters doesn’t make it racist. Though told from the British point of view, it shows that viewpoint change from dismissive contempt and naked fear to respect and even admiration. The famous (and entirely fictional) salute the departing Zulu army pays to the garrison survivors is returned with their – and our – gaze of awe and wonder.

Adapted from an article in Cinema Retro No 28 (c) Sheldon Hall 2014

Sheldon Hall is a Senior Lecturer in Stage and Screen Studies at Sheffield Hallam University. An expanded second edition of his book ‘Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It – The Making of the Epic Movie’ will be published later in the year by Tomahawk Press. For advance orders and inquiries, visit tomahawkpress.com or email sales@tomahawkpress.com, with ‘Zulu’ in the subject box

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments