The day the New Wave came crashing down

Profile: François Truffaut - They were the Lennon and McCartney of French cinema. And then Jean-Luc Godard spurned his oldest friend

In the summer of 1949, two young French film buffs were photographed attending a festival in Biarritz.

It was a small event, a hardcore cinephile affair specialising in overlooked films – "Cinéma Maudit" – and the pair, both budding critics, weren't exactly visiting in style. They were lodged in the dormitory of a local lycée, where the picture was taken. Their names were François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, and as a piece of French film history, the photo is roughly equivalent to an early portrait of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, en route to play their first dates in Hamburg.

The photo appears in a new documentary, Two in the Wave, about the friendship – and rancorous falling-out – of the two best-known names in the nouvelle vague (New Wave), the group of critics-turned-directors who revolutionised French cinema. A boyish Truffaut, then 17, is grinning, his shirt flopping off his shoulder – not in a dandyish way but possibly because he got distracted by thoughts of the day's screenings while getting dressed. Godard, in profile, hovers in the background in bouffant hair and horn-rims, cultivating the saturnine inscrutability that would become his trademark.

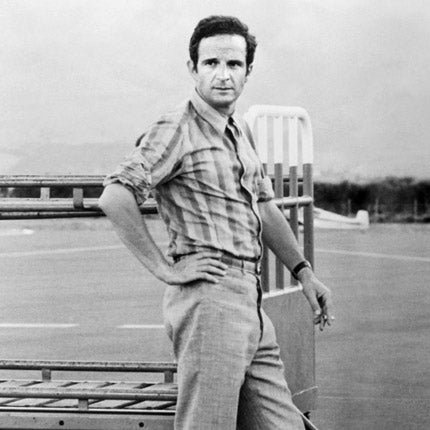

Lennon and McCartney may seem a facile comparison, but given the way in which the two film-makers are perceived today, it's not far from the truth. Godard was always considered the Lennon of the French New Wave – its aesthetic and political radical, the guru embodying the hard edge of the 1960s spirit. Truffaut, meanwhile, came to be seen as the "Paul" of the group – the one with the tunes. He was the entertainer who made approachable, commercially successful films, who joined the mainstream – and even ended up playing a cameo role for his fan Steven Spielberg, in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. And yet, with a new retrospective at London's BFI Southbank – plus the re-release of two Truffaut classics – we have the chance to see, even in some of his simplest films, that the early passions of an omnivorous movie buff fed into a sometimes self-effacing, but utterly fluent mastery of film language.

François, wild boy

Truffaut – who died in 1984 of a brain tumour – was repeatedly accused in his lifetime of selling out. But at the start, he was the tearaway of the circle that included Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette and Eric Rohmer. A habitual truant turned autodidact, Truffaut escaped from his unhappy childhood through obsessive cinephilia; his early years include episodes of debt, theft and army desertion, spells in juvenile correction and prison. When Truffaut started writing about cinema, he quickly established himself as a firebrand. A notorious 1954 article in the film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma called for a clearing-out of French film's drily professional ancien régime, and for a new generation of cinephile directors creating truly personal work. The article has gone down in history as an early manifesto for the nouvelle vague.

In 1958, Truffaut got himself banned from Cannes, after denouncing the festival as a clapped-out institution. A year later, he triumphed there with his first, quasi-autobiographical feature The 400 Blows – one of the great films about adolescence. Its off-the-cuff shooting style and vital disregard for formality – and the irresistible vibrancy of its 14-year-old star Jean-Pierre Léaud – changed the game for French cinema, and for a generation of film-makers worldwide. It was as a result of this film's success that Godard got his own debut Breathless off the ground – thanks directly to the efforts of Truffaut, who provided the original story.

Truffaut and Godard soon took very different directions. Godard left the path of conventional narrative, never to return, while Truffaut undertook a diverse series of genre explorations. Shoot the Pianist (1960) and Jules et Jim (1962) furthered the New Wave's reputation for youthful creativity, with their romanticism, urgency and self-mocking humour. Truffaut then undertook coolly conceptual science fiction (Fahrenheit 451, 1966), austere costume drama, assorted tributes to his idol Alfred Hitchcock, and a series of increasingly flimsy comedies that took Antoine Doinel, the hero of The 400 Blows, into adult life.

The various romantic entanglements of Jean-Pierre Léaud's Doinel echoed Truffaut's own. The director was married from 1957 to 1965 to Madeleine Morgenstern, with whom he had two daughters, but he had affairs with several of his lead actresses, including Jeanne Moreau, Catherine Deneuve and her elder sister, the late Françoise Dorléac. He finally settled down, for the three years before he died, with one last muse – Fanny Ardant, star of his comedy-thriller swansong Finally, Sunday!. The amorous agonies of the final Antoine Doinel film Love on the Run (1979) may suggest a man who couldn't grow up any more than his protagonist could – but its back story is nothing if not personal.

The rift with Godard

Through the 1960s, Truffaut continued to champion Godard, and stood shoulder to shoulder with him in shutting down Cannes in May 1968, in solidarity with France's workers and students. But politics would pull the friends apart. In 1973, Truffaut made, and appeared in, a fond backstage comedy about film-making – the soon-to-be re-released Day for Night, a hectic ensemble confection that beats Robert Altman to some of his most celebrated tricks. The world loved Day for Night – but not Godard. He wrote to Truffaut, accusing him of being a liar because he hadn't undertaken a political critique of the film industry. Quoting a line from the film, he complained, "You say films are trains that pass in the night, but who takes the train, in which class, and who is driving it with a management snitch at his side?" Adding chutzpah to injury, he then invited Truffaut to invest 10 million francs in his next feature.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Truffaut retorted with a long, furious epistle attacking his old comrade as a hypocrite and poseur. The friendship was over. Truffaut seems to allude ruefully to the episode in his extraordinary, anomalously bleak The Green Room (1978), adapted from Henry James. In it, Truffaut plays an obituary writer morbidly obsessed with commemorating all the dead in his life – all except one man, a friend with whom he quarrelled and with whom he can never be reconciled.

The career and the classics

Since those days, Godard's catalogue of rigorous and recherché explorations has given him the high ground as an innovator – leaving Truffaut to be remembered as a conservative whose films are the latterday equivalent of the "cinéma de papa" he pilloried in his youth. But the new BFI Southbank retrospective shows that even some of Truffaut's simplest films reveal complexities, contradictions and often troubling depths, couched in unshowy but supremely confident style. The 1964 drama Silken Skin – also being re-released – is one of cinema's more sensitive and sober depictions of bourgeois adultery. Starring the quietly incandescent Françoise Dorléac, it is one of several Truffaut films about weak-spirited men losing their bearings over magnetic women. The most famous is Jules et Jim, but it's not the only Truffaut film in which the depiction of amour fou now looks like an almost parodic instance of French romantic misogyny.

However, there are two great femme fatale films. The Bride Wore Black, with Jeanne Moreau as an inscrutable revenger, reduces the Hitchcockian thriller to almost algebraic clarity. And the nearly-forgotten Mississippi Mermaid – with Deneuve as a bad, bad woman and Jean-Paul Belmondo as her adoring sap – hits a level of strangeness that puts it in the Buñuel league.

Truffaut also made a series of austere period pieces that strip away the reassuring clutter of costume-drama values. Among them is The Wild Boy (1970), in which Truffaut himself plays a scientist educating a feral child; you can see its echoes in a strain of demystificatory historical dramas, from Herzog's similarly themed The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser to Haneke's The White Ribbon.

Truffaut never actually set out to be an iconoclastic director. "I never thought of revolutionising cinema," he declared. "I always loved cinema, but wanted to do it better." An ardent admirer, Martin Scorsese, commented: "In Truffaut, you could feel the awareness of film history behind the camera, but you could also see that every single choice he made was grounded in the emotional reality of the picture ... if you look at those movies carefully, you will see that there's nothing extraneous or superficial." Truffaut took as his touchstones Jean Renoir and Roberto Rossellini, for their stylistic modesty – directors who had "freed themselves of all complexes about cinema". Whatever complexes about life appear in his work, Truffaut's film-making is bracingly unneurotic. Not all his films are classics – yet Truffaut himself has become a classic, in a way that even his pugnacious young self might have approved.

The Truffaut season runs at BFI Southbank from 1 Feb. 'Silken Skin' is released 4 Feb; 'Two in the Wave' 11 Feb; 'Day for Night' on 18 Feb

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks