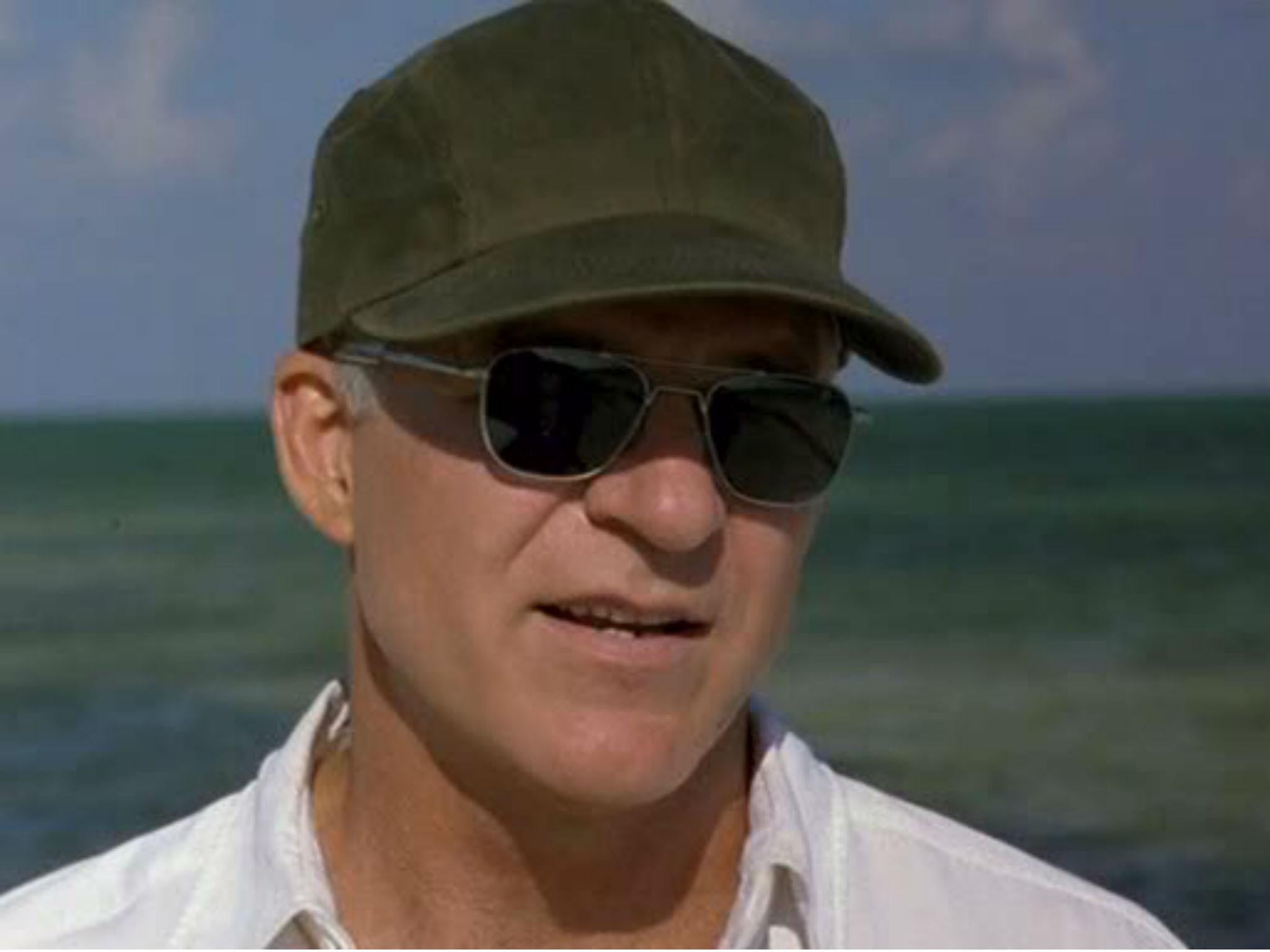

Steve Martin interview: 'I’ve always had empathy with comedians and their struggle'

Steve Martin is one of the latest celebrity participants in MasterClass, an instructional website where artists charge a fee to share insights about their craft

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s no secret that the Steve Martin of today is very different from the stand-up comedian who came to prominence in the 1970s, wearing a deliberately passé arrow through the head and strutting his stuff to “King Tut”.

He’s a more measured ironist now, focused on his literary efforts, bluegrass music, Broadway shows and live performances. Outside of projects like his 2007 memoir, Born Standing Up: A Comic’s Life, getting Martin, 71, to talk now about his days as “a wild and crazy guy” or movies like The Jerk is like asking him to make you one of his bad balloon animals: it ain’t gonna happen.

So it is perhaps a surprise that Martin is one of the latest celebrity participants in MasterClass, an instructional website where artists share insights about their craft. Despite a reluctance to revisit the past, Martin makes a sincere tutor, for a $90 (£70) course of 25 episodes.

“I definitely tried to make it about creativity and also about life,” Martin said. “All my thoughts about comedy are metaphorical, applying to anything else.”

Martin spoke further about why he returned to this chapter of his career, what lessons it offers and the extent to which he keeps up with comedy today.

What made you want to do a project like this now?

I’ve always had empathy with comedians and their struggle. I know it inside out, and the struggles remain the same. I’m always rooting for comedians, especially now that I’m older. Your competitive edge is off. You don’t have to worry about somebody being funnier. Because, as I say, there’s always someone funnier.

Is it fair to say you shy away from invitations to talk about that era of your career – the retrospective thing does not come easily for you?

Yeah. You can only talk about it so much. And then there’s diminishing interest in the old you, both from the public and yourself. About 20 years ago, Kevin Kline called me and said: “I’m teaching a course at Juilliard in comedy. Would you like to stop by and talk?” And I thought: there’s nothing you can teach about comedy. I don’t know what that would even be. But I went to the class, and they did some scenes, and I thought, Oh, there is a lot to teach. Through the years, I’ve gathered some knowledge that can be transferred. I actually feel more creative in the last ten years than I have in that whole time.

When you were starting out, did you have people you considered mentors or instructors?

No. However, I did have heroes, like Jack Benny or Jerry Lewis, and little-known entertainers that I’ve seen through my life. My hero, when I was 11, was a guy named Wally Boag (a Disneyland stage performer and street magician). When I got into college and I was an ironist, I thought, OK, bad balloon animals will be my staple. Fats Johnson was an entertainer who wore rings on his fingers, played guitar and sang and was funny. I said, “Fats, what do I wear onstage?” He said, “Always look better than they do.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

One of your episodes is about constructing a stage persona, an idealised version of who you want to be in performance. Is this what you thought you were doing at the time?

Certainly, it’s an evolution. It’s not a ray of light that strikes you. When I first started to think, “I’ve got to be a person up there – how do I be a person?”, all I did was take jokes that said “A guy walks into a bar” and change it to “I walked into a bar.” That was a simple thing to think about. You make everything about yourself.

There’s a moment after the fact where you realise, oh, I’m constructing something. At first, you’re just trying to make it through the 15 minutes. There’s absolutely no ideological thing going on – you’re just trying to survive. But what comes is the Platonic version, which is pure. Then you try to have the real version live up to the Platonic version that’s in your head.

Does it feel weird to be talking about a Platonic ideal of stand-up comedy?

I studied philosophy in college, so I default to those few references that remain.

Was there a point, at your peak, where audiences were coming just for the persona and not the material – that essentially anything you delivered in that guise worked?

I found it was actually almost the reverse of what you’re saying. Because once that persona was established, it was very hard to bring in new material. The thing that was expected was so precise. And I loved being precise onstage. I didn’t want to mess with it. But the only way out was to stop. But I had a great place to go – the movies.

Did you help choose your vintage stand-up and movie clips in the lessons?

I only saw those after the fact. I always let other people choose the bits, because I don’t know what works today. I like the idea that someone who wasn’t even born in that era is picking them.

What does that spare you from?

Having to look at it, for one thing. But also having to understand what works today. Unfortunately, most comedy is ephemeral. People want their own generation of comedy. You look at an old single-panel cartoon from the 1890s, you struggle to figure out what was funny about it. It’s a lengthy paragraph, as opposed to a Roz Chast cartoon in The New Yorker.

When you work on a project like this, does it make you want to do stand-up again?

The truth is, I work with Martin Short and I tour with the Steep Canyon Rangers, and that’s exactly what I’m doing. [Last year, when Martin performed as a special guest at a Jerry Seinfeld show at the Beacon Theatre] this thing came out that said, ‘Steve Martin’s Return to Stand-Up’. No. It was stuff I’d done for the past 10 years, only a 10-minute version of it. When I work with Marty, sometimes I wonder if I could do stand-up. Then I think, I don’t want to do an hour on my own and try to remember what comes next. I really like what we’re doing.

By doing this project, are you saying, in a sense, I’m putting this era of my life to bed?

Yes. It’s a place to put all this esoterica. It has absolutely no use to anybody, except comedians or people who want to be in show business, or people who want to be creative.

You tell a story in one of the episodes about seeing a prime performance from Sam Kinison, whose world did not exactly intersect with yours. Did you get something out of that experience?

Oh, yeah. You know when someone’s killing it. But not always immediately. Sometimes it takes a couple of weeks to think about it. You have to go, What did I just see? I say the goal is not to be good – it’s to be great. The idea is to have the audience leave, and say, “You’ve got to see this.” You have to work backwards from that result.

Do you keep up with what’s happening in stand-up now?

Only a little bit. I recently watched Dave Chappelle’s (Netflix specials), really funny. And I didn’t know what to expect, because I had never seen him. I was really surprised because I didn’t know what to expect. I thought it was going to be more radical, in its style, and more flamboyant, in some way. But it was so straight-ahead and entertaining and engaging. I was really knocked out. I expected him to be scary, and he was friendly and charming. Then I watched Bill Burr’s Netflix (special). And really enjoyed that, too. I had never heard of him until I went, “What’s that?”

How do you think the Steve Martin of the 1970s would react to the work you’re doing today?

Except for a few moments early on, I never saw into the future. I never thought, This is what I’m going to be doing. I knew what I didn’t want to be doing. But I was never guided by an overreaching plan, except moment to moment. I guess I just contradicted myself. But even in the master class, I say, “I realize this contradicts what I just said.” I’d love to count the number of times I said that.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments