Steve Coogan interview: 'I don't mind if some people hate me, as long as it's not everyone'

Lurid tabloid tales about his private life turned Steve Coogan into a Hacked Off warrior. But with his latest film, Philomena, a hot tip for the Oscars, he may be entering a new phase of life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There are quite a few things that make Steve Coogan angry. He has no time for vacuous celebrities. "I get annoyed, I GET ANNOYED about celebrities who need to please all the people all the time, in some sort of nebulous, soupy, bland way. Who would never say anything remotely controversial because it might affect their career. I think those people are pathetic, frankly."

Nor does he like anyone who has too much conviction. "People who are overly certain make me angry."

Certain tabloid newspapers make his spittle fly: "Being personal and behaving like a school bully, like some proprietors and editors do – UTTERLY PATHETIC."

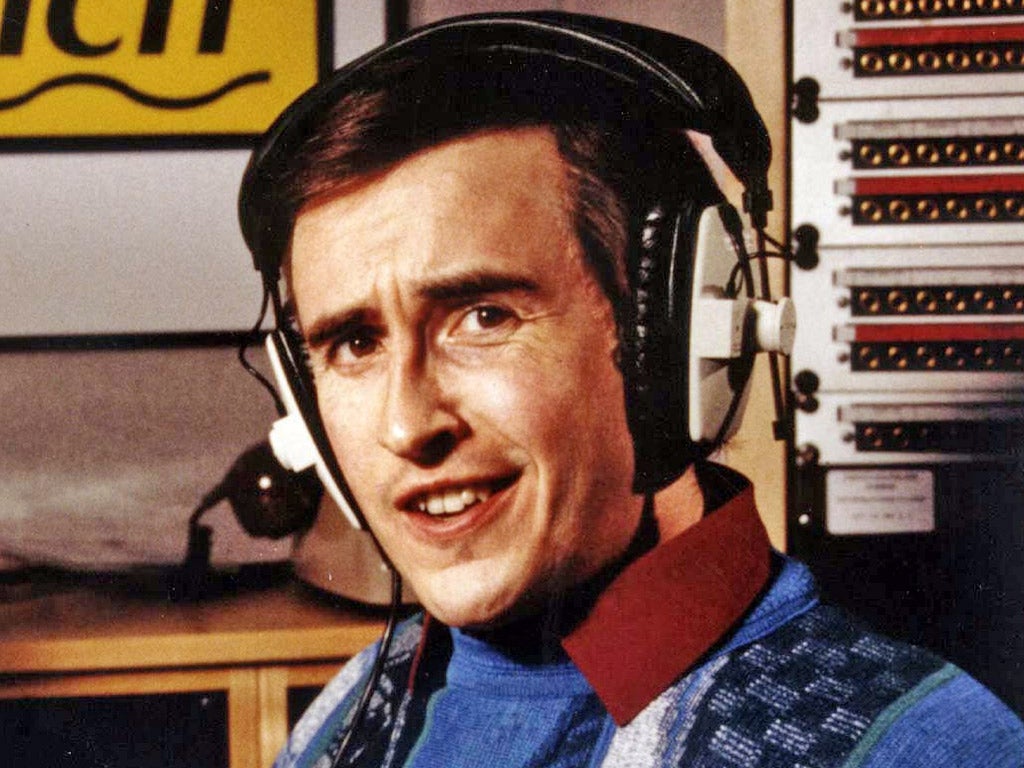

And what riles him, perhaps most of all, is when people muddle him and his most famous creation: "When reviews say, 'Oh, it's a bit like Alan Partridge'. It's lazy. What they're assuming is Alan Partridge is actually me," he clears his throat. "Because I came first."

If all of this makes Coogan, 48 – the man behind one of the era's defining comic characters, yes, but also prolific actor in Hollywood and at home, writer, producer and, lately, avenging angel of the Leveson Inquiry – sound a bit down on life, that is not the whole story. Like Partridge manning a radio phone-in, he just likes a rant now and again. When he gets going on one, you can tell he enjoys it; they tend to end with a snigger or a twinkly sideways look.

There are quite a few things that make him happy, too: writing, driving, the great British outdoors, proving people wrong and, currently, the Andrew Mitchell "plebgate" saga. "It's better than any mini-series," he says. "That's the stuff I find really entertaining." In another 20 years or so, he will make a glorious grumpy old man, still skewering Middle England banality, doggedly tramping the Lake District fells and buffing his fleet of luxury cars. For now, he is just a bit of a glass-half-empty person. "Which I don't like about myself. Just slightly pessimistic. Malcontent. Not a lot. I like my life."

Today, rants aside, he is in a good mood. And well he might be. Alan Partridge's big-screen outing, Alpha Papa, was widely held to be a triumph this summer. He is not long back from Italy where he spent a few weeks zipping between Genoa and Capri in a Mini, filming a second series of The Trip. "Beautiful. Eating fantastic food, drinking wine, sailing on yachts… The only downside was I had to do it with Rob Brydon." And now, after years of near-misses and flops, it looks as though he might have his first copper-bottomed hit film.

An Oscar in the offing?

Philomena, a labour of love which Coogan co-wrote, co-produced and in which he co-stars with Judi Dench, premiered at the Venice Film Festival where it got a 10-minute standing ovation and the kind of reviews that lead to Oscar rumours. We meet the day after its London premiere, where it made all of his family cry. "So that's a good sign," he says, trying not to look too thrilled. Trim in a tweed jacket, with newly serious hair, Coogan looks like a man who has it made. Has he? "I just feel happy when I'm writing. I feel like I've something approaching a proper job," he says, through a mouthful of chocolate. "I'm comfortably off. I'm fortunate that I'm now surrounded by people who facilitate me being creative. I don't have to open any envelopes that have windows on them. For example."

Four years ago, it was a different story. Coogan was breaking into Hollywood with Ben Stiller's Tropic Thunder, Night at the Museum 2 and a few romcoms to his name. "Playing part number four in very thankless, unremarkable – enjoyable on one level – studio comedies. I felt like I was punching below my weight a bit." You were funnier than those films? "Yes. Good people making them, but I was just treading water."

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Back in the UK, Michael Winterbottom was seemingly the only director who didn't want to cast him as a paler version of Partridge. "In certain parts there was a vindictiveness: 'We're not going to let you not be Alan Partridge.'" So he teamed up with Winterbottom on The Trip, and made his career troubles into a sublime sitcom. It won him his first post-Partridge Bafta.

Around the same time, he spotted a headline: "The Catholic Church sold my child." The article, by former BBC correspondent Martin Sixsmith, told the true story of Philomena Lee, an Irish girl who was banished to a convent when she got pregnant, aged 18. Forced to work in the laundry there, she was allowed just one hour a day with her baby until one day, a rich American couple took him away for good. Fifty years later, Philomena revealed her secret to her daughter who enlisted Sixsmith to track him down.

Sixsmith's book came out in 2009 and Coogan optioned it immediately, without reading it. "Just to alleviate my own boredom." Then Jeff Pope (writer of Pierrepoint, about Britain's most prolific hangman) came on board as co-writer and Stephen Frears as director. The result is an extraordinary film – part detective mystery, part tear-jerking family drama, part odd-couple comedy, which pits the middle-class, metropolitan, atheist journalist against the working-class, devout pensioner, Lee.

Coogan was raised a Catholic, one of seven children, in Middleton, north Manchester; his mother – the same age as Philomena – also fostered children from the Catholic Rescue Society. "I'm not a Christian although I was raised with values that I think are important", he says. "What I love about this story is the idea of self-doubt. There's something irritating about a glib, enlightened person looking down his nose at people who have simple faith – and yet maybe I'm guilty of that sometimes, too. Even though I regard myself as a lefty-leaning, liberal-ish, intellectual-ish sort of person, if you showed me a room full of those people I would hate them all. So it's having that conversation in my head and then putting it into the characters."

Having started out as an impressionist, landing his first TV job on Spitting Image aged 22, Coogan has done his most interesting work playing real people. As with Tony Wilson and Paul Raymond, his Sixsmith is a hybrid. "Half Martin, 30 per cent me and 20 per cent something else. I've not settled on the percentages," he says.

"Martin is not as cynical, or angry – that's more me. It was cathartic for me, a way of working stuff out, which I think is a normal part of the creative process." It is fair to say that Coogan – who based The Trip on a character called "Steve Coogan" and admits to ploughing his own most troubling thoughts into Partridge – subscribes to the acting-as-therapy model more enthusiastically than most. He guffaws. "Well, you know, I've got a lot of noise going on in my head. I've got to do something with it."

There is also a certain obvious irony to the fact that Coogan is playing a journalist. He was one of the most memorable witnesses at Leveson, channelling his frustration at years of stories about dalliances with lap dancers and cocaine into righteous ire on behalf of other, less lurid, victims. He is now one of Hacked Off's most vocal activists, matching public donations pound for pound and speaking up for stringent press regulation. "I don’t like celebrities bleating on about things. I'd rather someone else did it, but no one else was."

Was he afraid of enraging the media? "No, it was a pain in the arse. What would have upset me 20 years ago, now I've developed a thicker skin. I'm more confident about who I am. I don't mind if a certain percentage of people hate me, or what I stand for. As long as it's less than 30 per cent," he pauses. "As long as it's not everyone. I can live with that."

A quieter life

In any case, his life appears quieter than it was in 2007 when the Daily Mail dubbed him "Coogan the Barbarian." He lives outside Brighton, near to Clare, his 16-year-old daughter from a previous relationship, in a mansion he shares with Elle Basey, a 23-year-old lingerie model he met when he was guest-editing Loaded. "And there I, ah, I draw a veil," he says. "I don't like to bang on about my personal life." He spends his spare time at his house in the Lake District. "I don't like going to sunny places on holiday," he says, with a baffled sneer. "I love Britain." He walks and reads – classic-car magazines and history books. This weekend, he went cycling on the South Downs. "They are not particularly exciting things", he says. "But I like doing them."

His professional life is rather more serious, too. Comedy leaves him a bit cold these days. "You get older and you want something more. I do love comedy, I'd just rather use it as a device to do something of substance." He is already working on a new screenplay with Pope ("He's workmanlike, good at the big picture. I over-analyse, like the myopia of it.") loosely based on his childhood. And he is writing his autobiography. It will only cover half of his life, probably up to when Partridge was born.

"So I don't have to roll my sleeves up and start slagging off people I work with and upset them. I'll only have to mildly criticise my friends and family. And they won't sue me." Will it be a happy tale? "Yeah. I'll try and manufacture some sort of trauma obviously. Make it more interesting. The content will be slightly underwhelming – 90 per cent of my childhood was very happy. I wasn't buggered by a priest, no one molested me. The only thing that happened was I had to go bed early and miss Bouquet of Barbed Wire. And I wasn't allowed a new Chopper for Christmas."

He was a dreamy child, always fantasising about films, or life in London, where everyone "lived in Mayfair, in expensive apartments, and drove Bentleys." At school, he was a talented mimic, but a reluctant one. "I wasn't the performing monkey. There were people in my class who goofed around and I thought they were idiots," he says. He is not sure what he would have done, had he flopped in showbusiness. "I dread to think. I probably would have drifted into teaching. God knows, I've never had a proper job."

Alan Partridge was born in 1991, when Coogan graduated from the Northern club circuit to working with Armando Iannucci on Radio 4's On the Hour. Two decades on, making a movie of Alan was, he says, the hardest thing he has ever done. Thanks to Philomena, he had not had time to work on the script and it wasn't ready. He spent eight hours a day filming, then three hours a night rewriting. Driven by a desire to wrongfoot everyone who expected it to be rubbish – "I didn't want them to have that pleasure" – Coogan ran the set like a mini dictatorship. "I didn't have time for people to say, 'I wonder what my character had for breakfast?' I don't give a fuck what your character had for breakfast, just stand over there and don’t bump into the furniture. And say the line like this. I knew what I wanted. It was like warfare – where no one gets killed, you just get really annoyed."

Even when he had a chance on Cromer pier, Coogan never dreamed of killing Partridge off. It would be like murdering his twin; he often finds himself wondering, "What Would Alan Do?" "Within all that madness, when you get it right, it's sublime, quite delicious to be there. I would do it again. The more successful the other things I do are, the more likely I am to go back and do more Partridge. I do like it, it makes me laugh. And I need a laugh sometimes."

‘Philomena’ is out on Friday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments