Sofia Coppola: My feminist retelling of 'The Beguiled' may 'flip' the male fantasy - but it's no castration wish

Coppola’s remake – starring Nicole Kidman, Kirsten Dunst and Elle Fanning – is a far cry from Clint Eastwood’s macho 1971 film

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As nicknames go, The Velvet Hammer perfectly suits Sofia Coppola. So called by Bill Murray – the star of her 2003 sophomore film Lost In Translation – it’s an apt title for a writer-director who seems soft on the outside, but clearly contains inner steel.

Like her films, she’s dreamy and softly spoken in person – the polar opposite to her bombastic father, Francis Coppola, director of Apocalypse Now. But with her latest film The Beguiled, she’s arguably cemented her place in the upper echelons of the directing elite.

When we meet, it’s a few days before she will claim Best Director for The Beguiled at the Cannes Film Festival, making her only the second woman in Cannes history to be awarded the prize, after Yuliva Solntseva won for her 1961 war drama Chronicle of Flaming Years.

After her Oscar and Golden Globe for writing Lost In Translation and her Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival for 2010’s Somewhere, which starred Stephen Dorff as an out-of-control actor, it’s yet another impressive accolade.

Taken from the 1966 Civil War-set book by Thomas P Cullinan, The Beguiled has already been heralded as a feminist interpretation of the story – far removed from the macho version starring Clint Eastwood, made by Don Siegel in 1971, the very same year they re-teamed for Dirty Harry.

“I would never think of re-making a film, but when I saw the film, it really stayed in my mind,” says Coppola. “I thought, ‘I’d love to see that story told from the point of view of the women, and what it must’ve been like for them and being cut off during war-time.’”

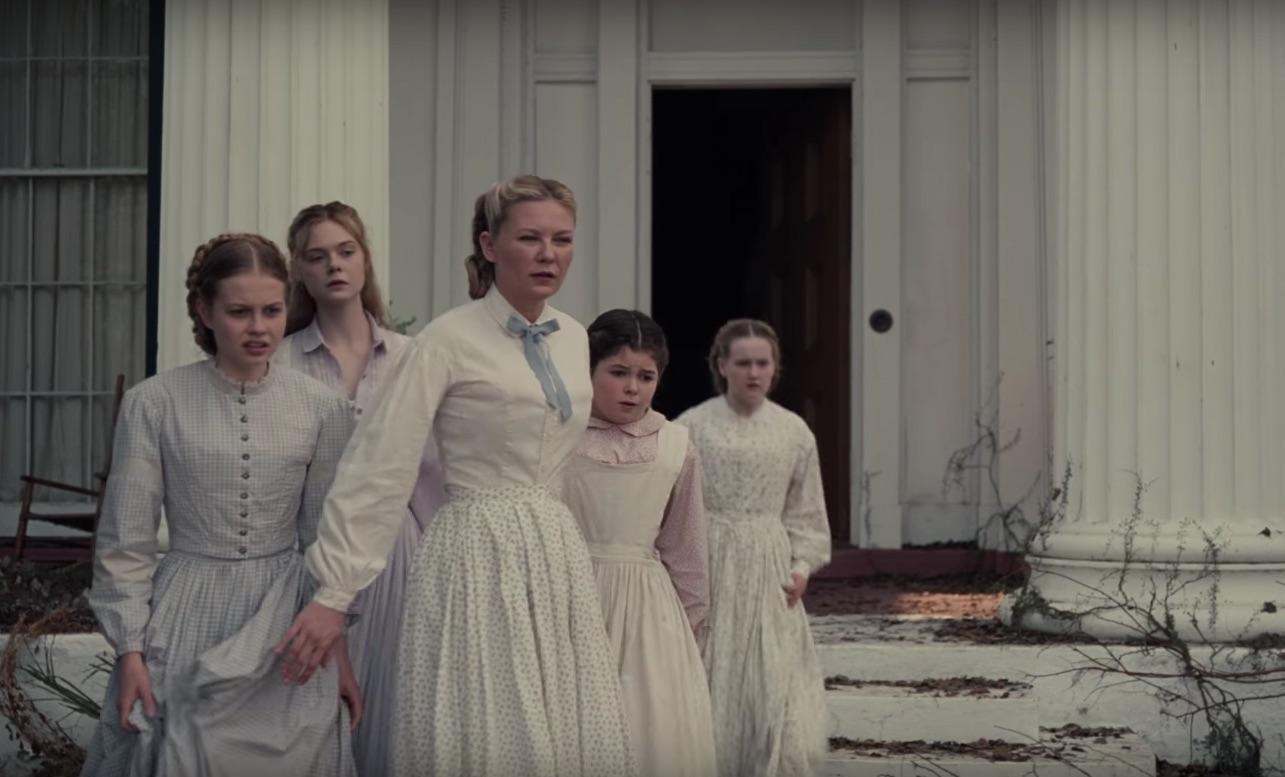

Set in the Confederate South, at an all-girls school run by Nicole Kidman’s resourceful headmistress, the plot begins as one of the pupils finds a wounded Union solider (Colin Farrell) and brings him in to recuperate. The spell he casts on the girls – particularly the repressed teacher Edwina (Kirsten Dunst) and the mischievous Alicia (Elle Fanning) – is startling.

Farrell, says Coppola, was the ideal choice. “I wanted him to be able to charm all the different types of girls – the thinking woman’s hunk!” she says, with a sly smile.

Shot on the same New Orleans plantation as the video for Beyoncé’s “Lemonade”, the lush photography by Philippe Le Sourd (DP on Wong Kar-wai’s sumptuous The Grandmaster) only adds to the sensuous feel in Coppola’s work. It’s a film about what’s not said, as much as what is.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“I think women especially communicate through gestures and glances,” Coppola explains. “So I thought that to try to convey what’s under the surface, and what they’re not actually saying, is interesting. And especially that the story is so repressed and claustrophobic; hopefully [you] can feel what they’re not able to say.”

For those who haven’t read the book or seen the Siegel version, there will be no spoilers here – but suffice it to say, the Velvet Hammer gets to strike a blow in the final act. “It starts like a male fantasy, being cared for, and it flips and turns into something different. That’s what’s surprising about the story,” Coppola remarks.

Siegel previously said the story is about “the basic desire of women to castrate men”. Coppola disagrees. “It’s not about that. But I understand how it can be interpreted that way.”

Predictably, the film has already been criticised on social media for removing Hallie, the African-American slave, from the narrative, with some commentators claiming Coppola is guilty of whitewashing the Civil War. Played by Mae Mercer in the original, Hallie tended to the Eastwood character’s wounds.

“I took that character out because I think that’s such an important topic and I didn’t want to treat it lightly,” Coppola argues. “I wanted to really focus the stories about these women of the South.”

Coppola’s previous film, The Bling Ring – the real-life story of a group of Los Angeles teenagers who targeted and robbed celebrity homes – was also singled out for failing to include the character of Latina teenager Diana Tamayo in the story. But Coppola is more than used to criticism at this point; her 2006 biopic Marie Antoinette was practically booed off the screen in Cannes. “I know everyone has different opinions,” she says. “I try to not pay too much attention. Just keep doing my thing.”

Splitting her time between Paris and New York, with her French musician husband Thomas Mars, the lead singer with rock band Phoenix, and their two daughters Romy and Cosima, Coppola’s ‘thing’ has seen her embrace the family business after her teen years saw her intern at Chanel.

Still, it wasn’t always this easy, notably when her father cast her in The Godfather Part III, replacing Winona Ryder, and her performance was pilloried. Would she ever act again? “Oh no, I forgot about that!” she chirps. “I’m not an actress. I love being behind the camera.”

Now 46, she’s become the key force in the Coppola filmmaking dynasty, with her father now 78 and seemingly more interested in making wine than films. Still, it’s never too late: Coppola’s mother Eleanor has just made her feature film directorial debut – at the ripe old age of 80 – with Paris Can Wait.

“She’s been trying to make it for six years,” says Coppola. “It was exciting to see her making her first narrative film, and her making something she really wanted to see, and showing a different point of view.”

Whether Coppola will ever follow into her father’s footsteps and make an epic is another matter. She made tentative inquiries about Wonder Woman (later to be directed by Patti Jenkins) and also pulled out of The Little Mermaid, a big budget retelling of the classic fairytale.

“I love making small, low-budget films where I’m really allowed to do it the way I want,” she says, “and I think when you have those huge franchises, there’s a lot of cooks in the kitchen and meetings in conference rooms.”

Her staged version of Verdi’s opera La Traviata not withstanding (made in collaboration with fashion designer Valentino, the filmed of the live production is also in cinemas in the UK this week) there’s a sense that her movies work best as intimate chamber pieces. The Beguiled feels no more lavish than her 1999 debut The Virgin Suicides, which also starred Dunst and boasted that same ethereal quality – and a similarly shocking ending.

“With video cameras, anyone can make a movie without a lot of money,” she says. Maybe that’s where she’s at her most comfortable: showing her independence.

The Beguiled opens on 14 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments