Seen any good books lately?

The liberties film-makers take with characters and plot when they adapt well-loved novels too often spoil the stories for fans of the originals, argues Arifa Akbar

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fans of Ian McEwan's wartime drama, Atonement, may have felt a dissonance when they saw Keira Knightley appear on their multiplex screens as Cecilia Tallis, not quite as they had imagined her.

The million-plus readers who pictured the serendipitous romance in David Nicholls's One Day might feel the same dissonance when they see the upcoming "film of the book" as perhaps might the legions of Haruki Murakami followers who have their imaginative bubbles burst when they revisit Norwegian Wood in its celluloid form next March. While popular works of fiction have always been ripe for cinematic reinvention, from Victor Fleming's adaptation of Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind in 1939 onwards, a growing rank of risk-averse film-makers appear to be drawing on bestselling books in hope of creating the box-office commercial equivalent. The larger-scale adaptations often target multiple book stories, such as the Harry Potter series, and are accompanied by a merchandising tie-in, in the hope that the most ardent will buy also buy the T-shirt.

A multitude of popular vampire, science-fiction and fantasy narratives have been adapted in recent times from Stieg Larsson's detective trilogy and Stephenie Meyer's Twilight collection to J R R Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy and Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials. These works have tread a conservative line to produce interpretations that stay fastidiously close to their narrative originals.

There are those who wonder what extra creative or interpretive dimension such faithful adherence will bring to audiences who have already read the book, while cynics suggest that trading on the loyalty of an already existing fanbase is an easy – and lazy – way of making a profit.

Next year promises the second part of the final Harry Potter series as well as DreamWorks' reimagining of the first film instalment of The Lorien Legacies series published by Penguin this summer (it will be called I Am Number Four), Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go (whose screenplay has been written by the novelist Alex Garland) and Barney's Version, an adaptation of the eponymous bestselling book about a man's harrowing experience of Alzheimer's disease.

But is this resulting in swiftly spun, conveyor-belt adaptations with an over-reliance on commercially successful fiction? Is something vital lost in translation when a 300-page book is reduced to a 90-minute film? And what is the value of such recycled fare to readers? Books have, after all, already been imagined in their heads and run, some might say, like an internal film-reel.

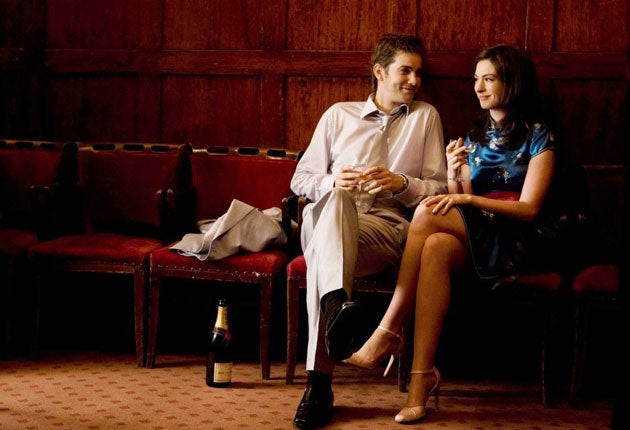

Nicholls, who has both written adaptations of classic novels for television and cinema, and written screenplays for his own novels including Starter for 10, starring James McAvoy and Rebecca Hall, and One Day, starring Anne Hathaway, feels that the "shrinking" process that a book undergoes for film need not render it redundant to readers.

As a screenwriter who has adapted Thomas Hardy's Tess of the D'Urbervilles and Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing, he thinks gains can be made in the conversion from book to film, even though it is a reductive process: "You have to reduce the material in the book but you can also bring out other qualities. In Starter for 10, James McAvoy and Rebecca Hall played their characters with a warmth and amiability that was not on the page. The characters in the book were rather more abrasive.

"With Tess, my adaptation was very much about fidelity to a book that I have always loved. Most of the key dialogue came from the novel but as soon as you put something on screen, of course it changes. In casting Gemma Arterton as Tess, she took the character in a different direction to give her a kind of strength and feistiness that is not on the page. Her performance made Tess feel modern and fresh." Yet authors have expressed befuddlement when they have not been part of the conversion process. Speaking at the Woodstock Literary Festival earlier this year, Bernhard Schlink, whose 1995 novel, The Reader, was turned into a film in 2008, starring Kate Winslet (and with a screenplay by David Hare), voiced his surprise at how far the film's take on Hanna Schmitz, a former Nazi guard, diverged from the role he had created for her in the book.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

The film adaptations with which authors tend to be pleased are largely the ones in which they have had some authorial control. Ian McEwan was brought on board for the making of Atonement and although the first screenplay distanced itself from the non-linear structure of the novel, Joe Wright, its director, decided to stay steadfastly faithful to the chronology of McEwan's story in the end. And it took Tran Anh Hung, the Vietnamese-French film-maker of Norwegian Wood, four years to gain approval from Murakami in order to adapt the book, and only on condition that Murakami saw the screenplay first.

The modern-day tendency towards author-friendly adaptations is far removed from bolder productions that abide by the principle that once a story leaves the author's head, it is the property of whichever film-maker who chooses to imagine it. Dr Yvonne Griggs, a lecturer at De Montfort University's dedicated Centre for Adaptations, thinks the bigger the interpretative gulf between book and film, the better.

"If you look really closely, films have always been adapted from existing texts. Most of Hitchcock's work came from other works, often by little known writers, a lot of Stanley Kubrick's work too. Texts that are revisioned rather than replicated are, as a rule, more successful. In the case of The Shining, Kubrick made it into an incredibly different kind of story from the one Stephen King wrote.

"The story actually changes so he was moving away from King's original and King was incredibly upset about that," she says.

Robert Harris, the bestselling author, has seen several of his books adapted for film, including his first novel, Fatherland, as well as Enigma, The Ghost, directed by Roman Polanski, and most recently Pompeii, which wil be released in 2011.

He believes that even authorial control over the film, or screenplay, cannot guarantee a happy ending. "Even if you have written the screenplay, you are still surprised by the outcome. You don't know what to expect because there is so much in it – the editing, acting, the pace – that determines a film's success. The actual screenplay is not a guide as to whether a film works. You can still get a bad film with a good screenplay." Although he was very happy with Polanski's treatment of The Ghost ("He is a very literary director, he was very loyal to the book"), Harris feels the biggest problem with adaptations arises from the inability of film-makers to identify what makes the book work.

"Normally books work for particular reasons. I'm amazed how often that thing that made it work has been surgically removed from the film in the process of making it. You are lucky if you get a director or screenwriter who works out what's good about a book. The people who go and see a movie are very different from the people who will read the book.

Ten million people went to see The Ghost – far more than the people who bought the book.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments