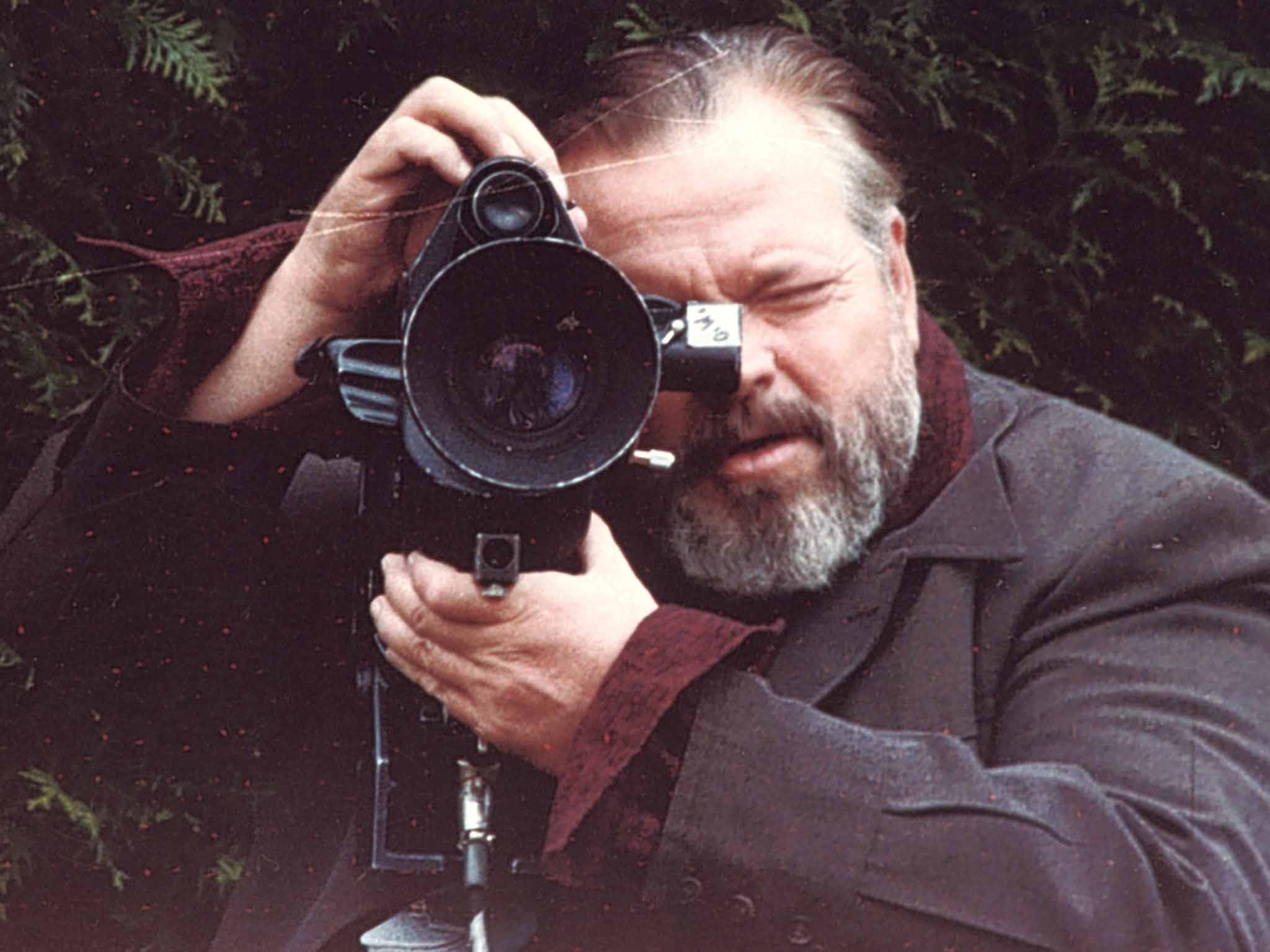

Orson Welles centenary: Britain has tended to regard the Citizen Kane star with a mix of reverence and disapproval

The BFI is celebrating Orson Welles next month with a season of his work

It is entirely in keeping with the life and career of Orson Welles (1915-1985) that the centenary of his birth is being marked in such excessive fashion. One of his first films was called Too Much Johnson (1938). As we are bombarded with new documentaries and tributes to the great man, there may be a sense of Too Much Welles. There are three rival new documentaries about him. Several of his films are being rereleased. An online campaign has just been launched to raise money to complete his unfinished late feature, The Other Side of the Wind, about a macho, Hemingway-like film director. The BFI is holding a lengthy season of his work.

Magician: the Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles, Chuck Workman's new documentary about Welles, begins with the celebrated sequence from Citizen Kane (1941) of magnate Charles Foster Kane (Welles) as a dying old man in his Xanadu retreat, dropping the snow globe and whispering hoarsely "rosebud". Unpicking what he means is supposed to be the key to Kane's personality.

Welles wasn't keen on the rosebud idea, which had apparently been thought up by the film's co-writer Herman J Mankiewicz. "It was the only way we could find to get off, as we used to say in vaudeville," he later told Peter Bogdanovich. Nonetheless, it is still the narrative device that is referred to most frequently when film-makers and historians are trying to understand Welles himself. One of the paradoxes about Welles is that he still seems as mysterious as ever in spite of the huge amount of information that continues to be unearthed about him. He is far too slippery a figure for biographers or critics ever fully to be able to explain.

Many countries have a claim on Welles. When Hollywood turned its back on him, he was forced to look outside the US for opportunities. "Like the fruit pickers, I go where the work is," he once joked. With his taste for blarney, Welles often seemed like an honorary Irishman. It was to the Gate Theatre in Dublin he came as a penniless teenager at the very start of his career, lying about his age and claiming to its founder Michael MacLiammoir that he was "a noted actor from the Broadway stage".

The Spanish think Welles is one of their own. He clearly loved Spain, worked there frequently and his ashes were buried there, in a well in Ronda. He identified strongly with Cervantes's daydreaming Spanish knight Don Quixote, the subject of one of his many unfinished films. Welles was always progressive in his politics but it is just another of the many contradictions about him that he never seemed especially bothered about spending so much time in a country under the rule of the dictator General Franco.

The former Yugoslavia has its claim on Welles too. He shot The Trial (1962) and The Deep (another of his unfinished projects) in Croatia and met his collaborator, muse and girlfriend Oja Kodar there. He also appeared in cameos in various movies shot in the Balkans. These included biblical epic David and Goliath (1960) in which he played King Saul, and The Tartars (1961), in which he was cast as a very hairy warrior leader.

"I often make bad films in order to live and I'm sorry to say quite a lot of these bad films were in your country," he explained to local interviewers. He was friendly with Yugoslavian dictator President Tito, whom he first met in 1946 and once called "the greatest man in the world today".

Mexico has its claims on Welles and so does Brazil (where he made his ill-fated foray to film It's All True). There have long been rumours that a print of his original version of The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), before it was savagely cut by editor Robert Wise after a disastrous preview in Pomona, California, is lurking somewhere in South America.

Welles spent a lot of time in Italy, where he shot much of Othello (1952) He had close ties to France, were he once proposed setting up his own film school, and links with Germany (the Munich Film Museum holds many of his unfinished films.) The Belgians have their call on Welles (he made Malpertuis, one of his better late films for Flemish director Harry Kumel.) He looms large in Switzerland too, albeit for his famously barbed quote about the country in Carol Reed's The Third Man (1949). "You know what the fellow said – in Italy, for 30 years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had 500 years of democracy and peace – and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock."

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

What of Welles and Britain? As early as 1946, film magnate Alexander Korda and Welles announced plans to make a series of films together in London. However, the Brits have tended to regard Welles with a strange mix of reverence and disapproval. One of his British biographers, the actor and author Simon Callow, features prominently in the new documentary Magician and you can't help but notice how Callow seems to chide Welles for his impracticality and bad business decisions.

"This is one of the great mysteries – how this extraordinarily bright guy was outwitted by so much less remarkable and intelligent people so often," Callow tuts of Welles's dealings. The biographer was also recently dismissive of Welles as a Shakespearian actor, calling him "oddly soporific" and "very disappointing". At the same time, Callow cites Welles's 1955 London stage production of Moby Dick as "one of the landmarks in British theatre of the 1950s".

Callow's ambivalence is mirrored by that of British critic Kenneth Tynan, who, after seeing Citizen Kane, called him "a gross and glorious director of motion pictures" and "a major prophet, with the hopes of a generation clinging to his heels". Tynan later recommended Welles to Laurence Olivier as a potential Winston Churchill in Rolf Hochhuth's play The Soldiers at the National Theatre. However, he also called Welles a "rogue elephant" who had "grown fat spreading himself thin".

The Brits were suspicious of Welles' sheer blustering, scene-stealing grandiloquence. The British director Michael Powell writes in his autobiography, Million-Dollar Movie, of trying to cast Welles as Odysseus. Welles was originally keen but his interest cooled when he realised that Powell intended to film a fragment of Homer's epic rather than the entire thing. Not even the prospect of being tied to a mast and emerging "naked as a god" after a shipwreck with "only seaweed to hide his noble parts" appealed to him. As Powell put it, "he wanted the Odyssey and nothing but the Odyssey."

Whether in A Man for All Seasons (as Cardinal Wolsey) or Jane Eyre (as Rochester), he often played British characters. However, Welles risked unbalancing many of the British-made films in which he appears. Sometimes, his presence could be magical. He has relatively little screen time in The Third Man, but his Harry Lime is still easily the most memorable character in the movie. By contrast, his preacher in John Huston's adaptation of Moby-Dick is so outrageously over the top in his hell and brimstone sermon about Jonah that the rest of the cast seem like pygmies by comparison.

In the latter part of his life, Welles seemed almost part of the British establishment. He was a regular fixture on chat shows. He had influential British friends, among them John Gielgud who became devoted to him after appearing in his Shakespearian adaptation Chimes at Midnight. Those who knew nothing of Citizen Kane or Harry Lime could recognise his voice instantly through his voiceover for the Carlsberg lager ad, "probably the best beer in the world", which showed incessantly on British TV in the 1970s.

The BFI Southbank's retrospective Orson Welles: The Great Disruptor' runs in July and August (bfi.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments