Fifty Shades of Grey and other BDSM movies: Bondage at the box office

Love hurts, but how much? With 'Fifty Shades of Grey' opening on Valentine's Day eve, John Walsh wonders if it will treat S&M gently or if, like most of its genre, it will try to swing both ways

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Anastasia Steele, a shy, pale, ponytailed virgin and student of English literature, is flown to the Seattle headquarters of his global company by the suavely handsome, obscenely rich, 27-year-old business mogul Christian Grey, she has high hopes.

As readers of Fifty Shades of Grey will recall, Grey has kissed her, just once, in an elevator and she hopes that he will now take her to bed and make love to her – gently, firmly, romantically. So it’s a tad disconcerting for Anastasia when he makes her sign a non-disclosure document, forbidding her from telling anyone about them – and then introduces her to his private torture chamber: a network of restraining cuffs, ropes, chains and shackles, and a gleaming accessories department of paddles, whips, riding crops and feathery floggers. It’s hard to imagine it’s the answer to a maiden’s prayer.

People may experience the same mixed feelings when they take their partners to the cinema this Saturday to see the film version of the global mega-seller; and, during the protracted scenes of domination and bondage, ask themselves if it’s absolutely the ideal Valentine’s date movie. So, when did the dark playground of tying-up, masking, flogging and submissiveness emerge from the niche of pornography to invade the cinema mainstream?

BDSM (bondage, discipline, sado-masochism) is the catch-all title for any behaviour that involves one person exercising sexual control over another. You can see the attraction for film-makers: it’s the paraphernalia, the dressing-up, the box of tricks, the chamber of delights. From Catherine Deneuve being whipped in Belle de Jour (1967) to the hapless gimp in Pulp Fiction (1994) to the partygoers’ masks in Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999), simply filming the pervy gear pitches the viewer into a world of transgression, in a way that mere naked flesh couldn’t do. It’s a visual shorthand that says: "Look! Sin! Pain! Forbidden desire!"

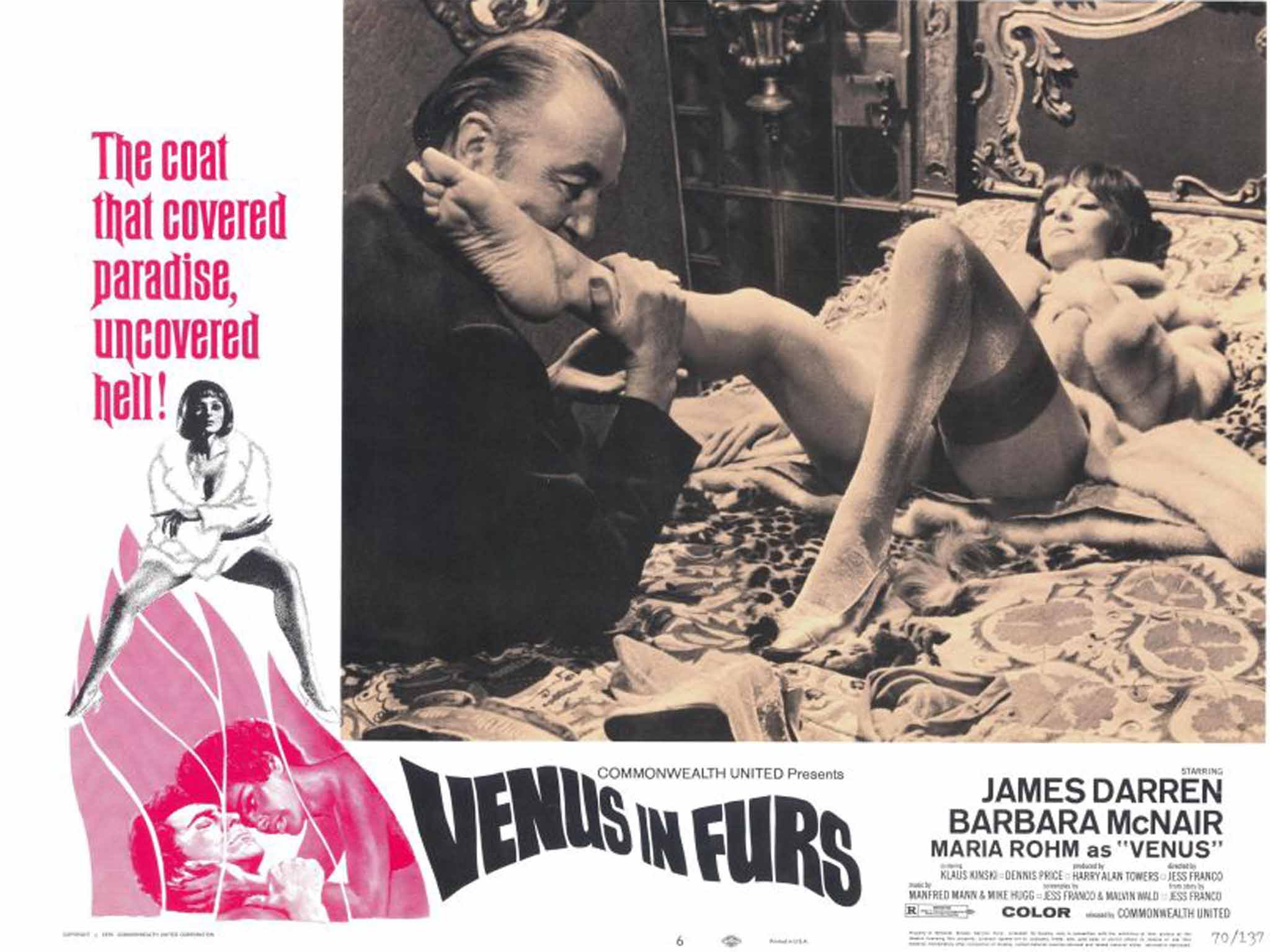

Two books stand out as Ur-texts for BDSM cinema. In Venus in Furs (1870) by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, a chap called Severin von Kuziemski becomes obsessed with a woman called Wanda von Dunajew and begs her to treat him as a slave, which she does, enthusiastically, in her basement. In The Story of O (1954) by Pauline Reage, a young woman photographer, known only by the titular monosyllable – as though she herself is just a hole or orifice – is brought to the Chateau Roissy by her lover René, and trained to be a sex slave; available to every man in his secret society. She is stripped, blindfolded, chained, whipped, branded on the buttocks and her skin is pierced.

Both books have been filmed, but the results must have disappointed connoisseurs of degradation. An Italian Venus in Furs, directed by Massimo Dallamano, was filmed in 1969, but the sex bits were considered too violent by the Italian censors; a heavily cut version, with added scenes, turned the story into a thriller. The Story of O was filmed by Just Jaeckin in 1975, the year after he made Emmanuelle, and was given similar soft-porn treatment, but with added chains, collars and masks. Unlike in the book, O finally turns the tables on her oppressor, Sir Stephen, and acquires some self-regard. Nonetheless, it was banned in the UK until 2000. Actually, 1975 was a bumper year for sadism and censorship: Barbet Schroeder’s Maitresse, starring a young Gerard Depardieu romancing Bulle Ogier, a dominatrix with an underground dungeon, came out that year, as did Pasolini’s unwatchably gruelling farrago of torture, child abuse and coprophagy, Salo or the 120 Days of Sodom. Both were also banned in the UK until 2000.

At the end of the 20th century, bondage and submission occasionally reared their heads in mainstream or art-house movies, as emblematic of beyond-the-pale perversity or a guarantee of bad character. In Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter (1974) Charlotte Rampling plays a rich, respectable Holocaust survivor who, 13 years after the war, discovers that the porter in her hotel is the Nazi officer with whom she had a sadomasochistic affair in the concentration camp; gradually they resume their relationship; a reaffirmation of the dark embryo inside the bourgeois body politic. The flashbacks hint that their connection was nuanced with impulses of care – but the shocking Nazi/victim theme eclipses all other considerations.

In Michael Winner’s The Nightcomers (1971) a prequel to Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw (filmed in 1961 by Jack Clayton as The Innocents), Marlon Brando plays Peter Quint, the brutish gardener who seduces the children’s posh governess Miss Jessel (Stephanie Beacham) and teaches the children things they shouldn’t know. His extreme villainy is signalled by his rough manners, thick Irish accent and the way he hog-ties Miss Jessel before having his evil way with her. It’s basically Lady Chatterley with some added fancy ropework.

One could argue that Adrian Lyne’s Nine and a Half Weeks (1986) was the first exploration of domination and submission as a respectable theme in modern cinema. Mickey Rourke plays a handsome, rich, un-knowable Christian Grey character – he’s even called Gray – John Gray, a Wall Street broker who falls for a divorced art-gallery employee called Elizabeth. Their relationship develops through a series of games, initiated by the smirking Gray, in which she’s blindfolded, made to pleasure herself at work, told to dress up and forced to have sex in public. Then punishment and jealousy enter their repertoire. But rather than help her to know herself better, the routines leave her emotionally blank: she ends up hungrily snogging a stranger in a porn club. Gray tries to establish a normal relationship by telling her about his past, but it’s too late. You see, the film asks, where this submissive malarkey gets you?

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Astonishingly, Secretary (2002) also features a Mr Grey as a chilly, demanding boss – a lawyer, E Edward Grey, played by James Spader, who employs the socially maladroit, self-harming Lee Holloway (Maggie Gyllenhaal) as a typist. He’s turned on by her breathless, submissive responses to being ticked off for spelling mistakes. Things progress through spanking, restraining cuffs and a saddle, as she starts to love being told what to do – she has an orgasm remembering how he instructed her on what to eat at the family supper.

The climax turns the tables on Nine and a Half Weeks. Lee sits at her boss’s desk, immobile, for three days, unwilling to move because he has ordered her to stay there until he returns. No amount of pleading by her family, her ex-fiance or the local media can shift her resolve – and E Edward Grey is so impressed by her obedience that he turns into a loving boyfriend. They end up as a happy couple, gleefully nursing their secret in polite suburbia. There’s little actual sex, but the spectacle of Ms Gyllenhaal crawling along a corridor with a letter in her mouth carries an unexpected erotic charge.

You don’t go to Michael Haneke for happy endings and The Piano Teacher (2001) doesn’t offer one. It gives us a character study of repression: Isabelle Huppert plays Erika, the titular teacher, a sour-faced, bun-haired, make-up-free, plain-clothed, not-quite-good-enough pianist who lives with her overbearing mother, cuts herself with a razor and visits porn rooms in sex shops to sniff spunk-crusted tissues. When a dashing student declares his love for her, she rejects him, then gives him a letter detailing all her desires – to be hit, kicked, degraded, bound hands-and-feet, wholly brutalised. She offers him a box of chains, ropes and implements of torture. She’s moved from being a stern dominatrix to a pleading masochist.

"The urge to be beaten has been in me for years," she tells him. "From now on, you give the orders." The student is appalled, then dismissive, then aroused, then conflicted and violence ensues. An awful warning seeps from this powerful movie: don’t instill a love of cruelty in someone, then try to reject them.

Where is British cinema amid these emotionally charged explorations? Playing it for laughs, is where. Personal Services (1987) lightly fictionalises the story of Cynthia Payne, the real-life madame of a Streatham brothel who hit the headlines in 1987 when police raided her premises and found elderly gentlemen in lingerie being spanked by young prostitutes. Terry Jones’s film, starring Julie Walters as ‘Christine Painter’, offers umpteen variants on a single, Monty-Python-meets-Benny-Hill scenario: a grand (male) member of the establishment, dressed as a schoolgirl/maid/nanny/bathing beauty, being awkwardly chastised by amateur dominatrices. "Is he here for the House of Pain?" one hooker asks the brothel clerk about a client. "No, it’s winkie-poos and bot-bots," comes the reply.

It’s a far cry from the Maitresse dungeon, the self-harming submissives of Secretary and The Piano Teacher, O’s branded buttocks, Severin’s love of pain in Venus in Furs, Severine’s love of pain in Belle de Jour, the Nazi-slave sex-fest and the to-and-fro of dominant and submissive as recorded over half a century of edgy, break-the-rules film-making. Whatever the verdict may be on Fifty Shades of Grey as a work of art, it’s a rare sighting of a British film that takes bondage culture as something other than a joke.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments