Eric Fellner: Bridget Jones's Diary producer says Gordon Brown helped revitalise the UK film industry

Exclusive: 'Gordon Brown changed the way in which films could be funded through tax credits'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He is one of the most powerful figures in British film, and Hollywood too, for that matter. Yet the low-key Eric Fellner is the polar opposite of the stereotype of the sharp-suited, fast-talking movie mogul.

Working Title Films, which he has co-chaired with Tim Bevan since 1992, has produced more than 100 movies, ranging from Four Weddings and a Funeral and Les Misérables to Bridget Jones’s Diary and The Theory of Everything.

The company’s productions have garnered almost 50 Oscars and Baftas but it’s not critical acclaim that drives Fellner, 56. “If you make films to try and get awards it’s a one-way ticket to misery because you just can’t guarantee it,” he says.

“What motivates me is business, I am a businessman. Beyond that the only films I want to make are films that I am really excited about.”

We turn to the reason he is giving the interview, for Fellner generally prefers to stay in the background. Sitting in a conference room next to his London office, the stubble-faced producer locks eyes and talks about one of his big passions, “to encourage people to go back to seeing films the way they were designed to be viewed... on the big screen” and to “bring film into the classroom”.

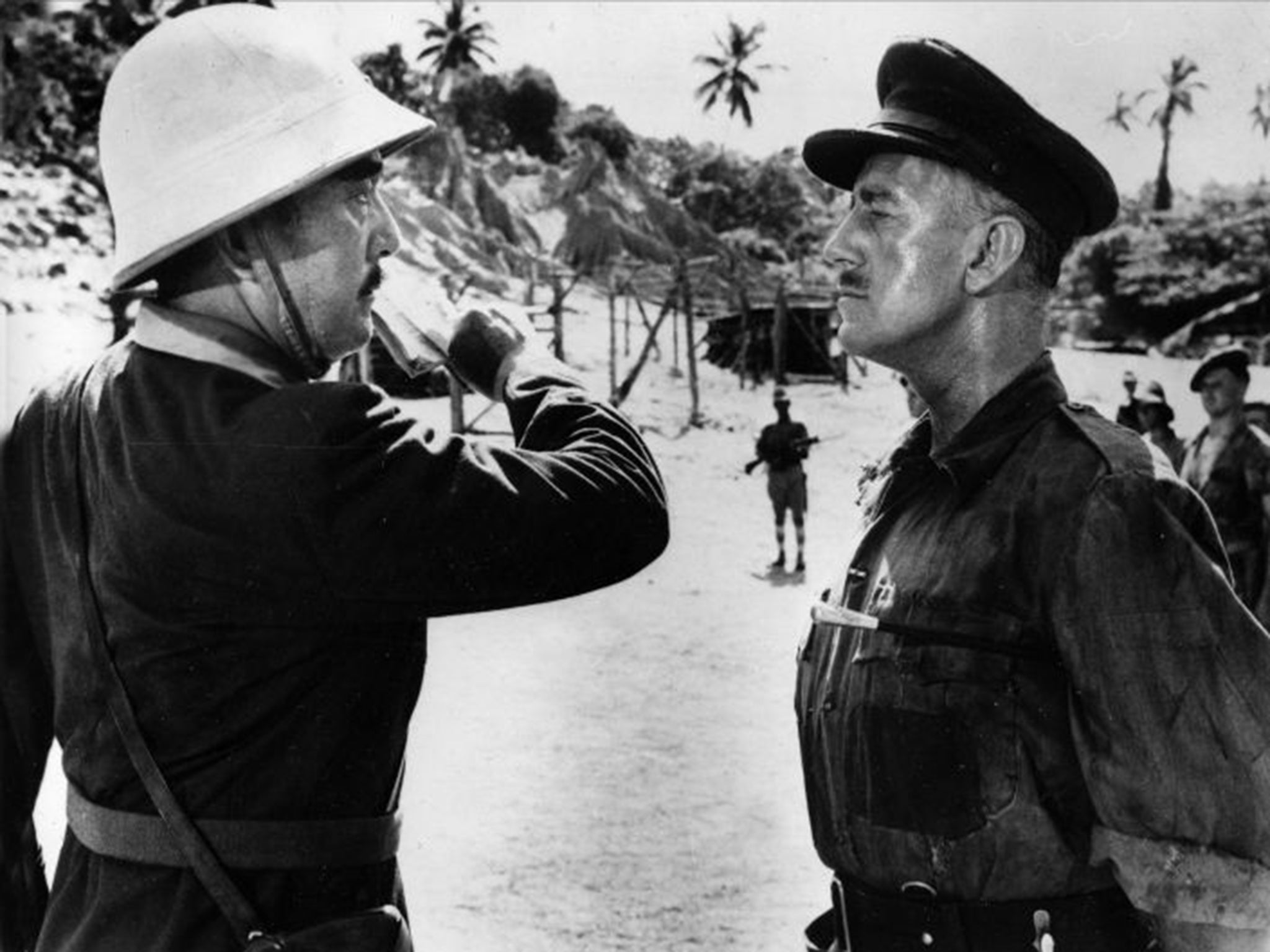

He chairs the Into Film charity and this week is the start of its annual festival, which will involve 400,000 five- to 19-year-olds at 2,700 screenings and events across Britain. Movies can be “a very powerful tool to open doors for teachers to find ways of engaging their pupils”, says Fellner. “You show them The Bridge on the River Kwai, and suddenly they will be interested in the Second World War – why was Japan in Burma? Where is Burma? What were we doing there? What was colonisation all about? What was the British Empire? All from just watching a movie.”

The father of five, who lives with his partner, Laura Bailey, in London, recently gave a talk to children in Tower Hamlets. “I could tell that the young people thought I came from another planet.” He was privately educated at Cranleigh School in Surrey but, while he had a “decent education”, he insists: “I didn’t have any ‘ins’, I didn’t have any contacts, so that’s what I try to explain to young people. If you really want it, even though it feels like a million miles from Tower Hamlets to the West End, it is do-able.”

He did not spend his childhood dreaming of making films, but enjoyed working on school plays. “I wanted to be in music, film or theatre. I didn’t know how to get into any of them. I knew I couldn’t be a performer, I knew I had no aptitude in front of an audience, but I wanted to be engaged in something that was creative.”

Fellner studied stage management at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama but dropped out after a year. It was the early 1980s, when there was a “closed shop” in film and theatre, but “music wasn’t unionised ... So I sent thousands of letters, banged on doors, and one day managed to get a job at a music video company right in the early days of music videos, as a runner”. He graduated from pop videos to film, and in 1992 joined Working Title Films.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

British film is in good shape, for which the former Prime Minister Gordon Brown deserves some credit, according to the producer. “Every year when the awards calendar comes around, you will always see British talent. Given that we are such a small piece of the global entertainment pie I think that says a lot about how the industry is going. Ten years ago, Gordon Brown changed the way in which films could be funded through tax credits.... This is the first time that one programme has been properly supported by consecutive governments and it is proving to be an amazing thing. It’s encouraging external investment from Hollywood studios and many other foreign companies that are coming here.”

Producing films is not easy. “It’s a very, very, very tough job because it’s straddling so many different things, from creative to business to psychological, to emotional.” And once shooting starts “it is quite tiring but also stressful, because you are spending two or three hundred thousand dollars a day”.

He cites a recent problem on the set of Bridget Jones’s Baby with Renée Zellweger and Colin Firth. “The ceiling fell down on a location we were in and suddenly you lose two or three hours, and then what are you going to do? You’ve got to get out of that location that night and you still have to get those shots.”

But he would not have it any other way. “We are incredibly privileged to have the ability to be able to tell stories and get them out there.”

Asked about the film he’s proudest of, Fellner picks Sid and Nancy, a biopic of Sex Pistols bassist Sid Vicious and his girlfriend Nancy Spungeon, and the first film he produced. He grins as he recalls the film being screened at the Cannes film festival in 1986. Hundreds of punks had turned up. “There was just this almighty fight as the front doors got smashed and the police got into a fight with the punks and it was like, ‘OK, I love the film industry’, and that was a great moment.”

The Into Film Festival, nationwide, 4-20 November; for more details go to intofilm.org/festival

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments