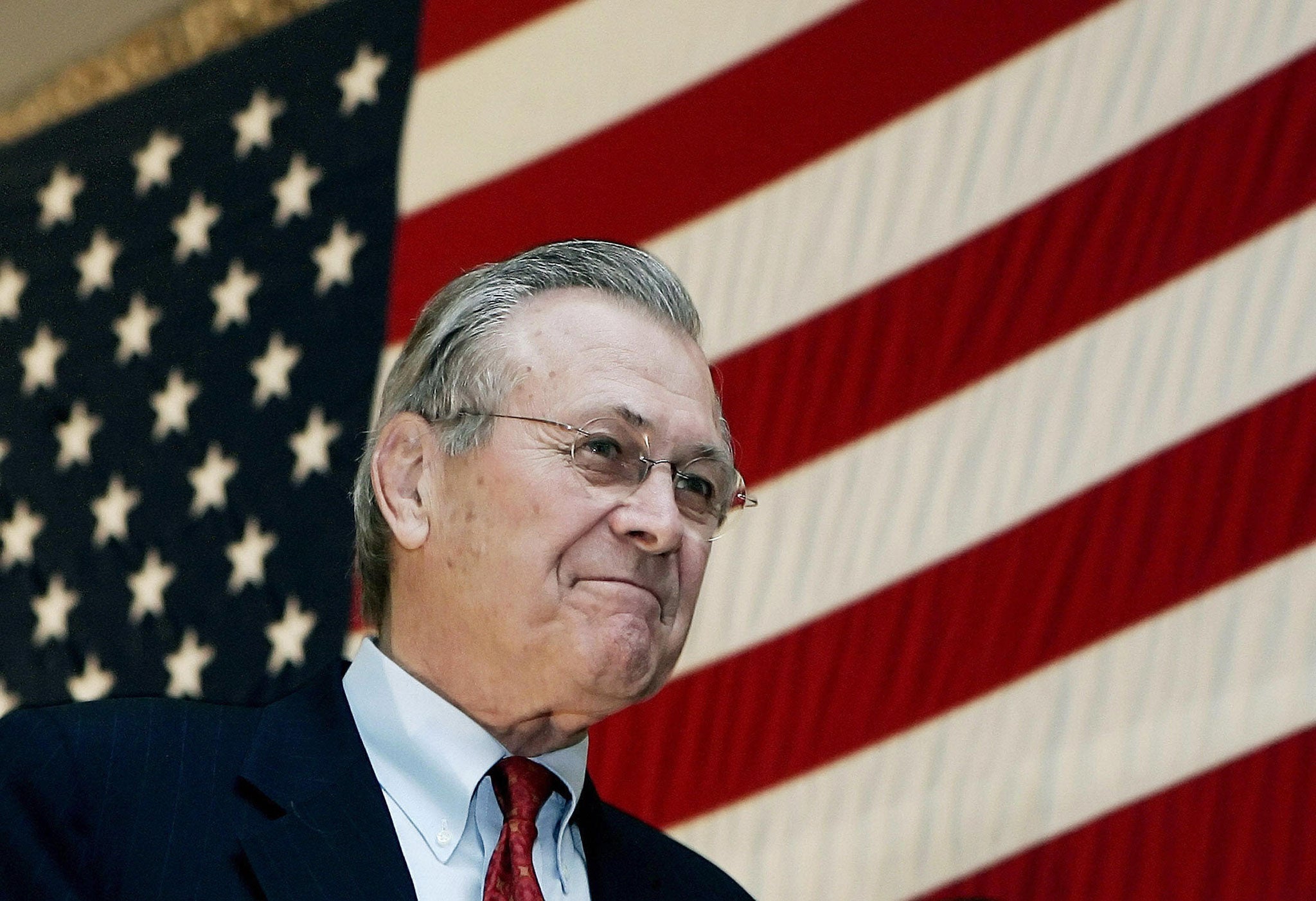

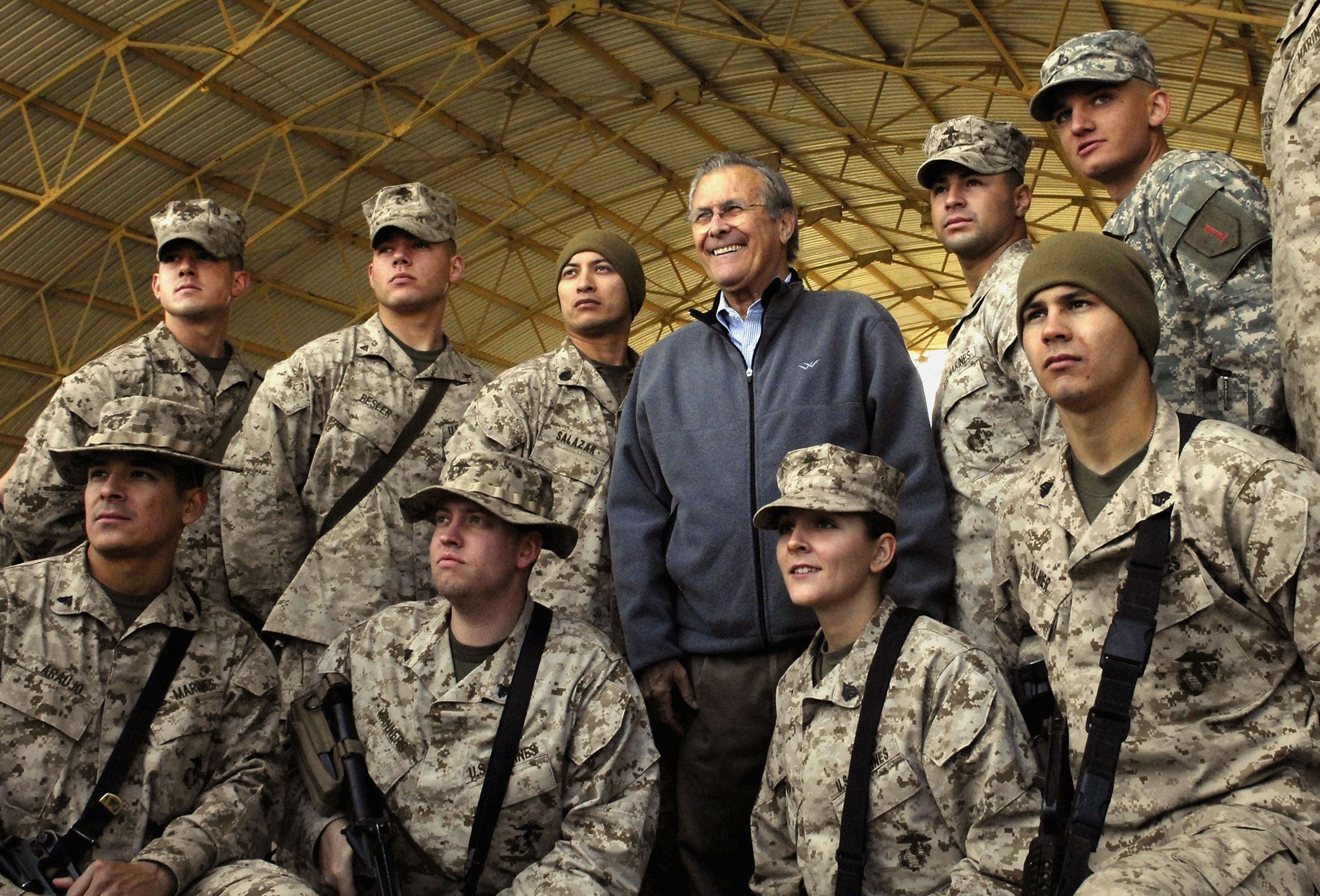

Donald Rumsfeld spills the beans on his time as US Secretary of Defence in Errol Morris' documentary The Unknown Known

Rumsfeld - a grinning and complacent presence on camera - fails to acknowledge any guilt or remorse over prisoner abuse, the absence of weapons of mass destruction and general mismanagement during the Iraq War

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Imagine you save a man from Death Row – and he ends up suing you for 'stealing' his life story. That is what happened to Errol Morris after his 1988 film, The Thin Blue Line. The Oscar-winning 66-year-old filmmaker (whose documentary, The Unknown Known, about politician Donald Rumsfeld, has just been released in the UK) is still perplexed by the legal action that Randall Dale Adams, the man wrongfully convicted of murdering a police officer in Texas, took against him.

"Shortly after I got him out of prison, he sued me," Morris remembers of a man he felt a huge commitment toward and who, at least initially, was very grateful to him. "Going back to that whole experience, I really worked very, very hard for over two years to investigate the case and put together the evidence that led to his conviction being overturned. I was instrumental, essential, in his release from prison." At one stage, Morris was even planning to mortgage his house to hire additional lawyers to get Adams out of jail.

It clearly rankles with the director that the lawsuit came between them. When Adams died in anonymity in 2010, Morris had long since lost touch with him. "My belief is that the lawyer made him think he had been taken advantage of by me," the director says. "He had a drinking problem that he never conquered completely. He was not a bad guy. The lawsuit was just sad. I, like everybody else, heard about his death after the fact. I had always dreamed that we would get reconciled and have an opportunity to talk to each other and figure it all out. But that was not to be. I feel that lack of resolution."

Morris remains proud of what he achieved through his filmmaking and detective work (he is a former private investigator) on The Thin Blue Line. "This was the first among so many exonerations, overturned convictions. Before The Thin Blue Line, people assumed that if you got convicted of murder and condemned to death, you did it. The Thin Blue Line rearranged, I believe, many people's thinking about the death penalty, about the fallibility of the justice system and so on and so forth."

It is striking how differently Morris talks about Randall Dale Adams and former US Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld. He cared deeply about Adams, but has no such commitment toward Rumsfeld.

In The Unknown Known, Rumsfeld – a grinning and complacent presence on camera – fails completely to acknowledge any guilt or remorse over prisoner abuse, the absence of weapons of mass destruction and general mismanagement during the Iraq War. He allows Morris access to his vast archive of memos. For every controversial moment in his career, there is inevitably a document that seems to justify his behaviour.

"Donald Rumsfeld was cooperative in every way. It is not made explicit, but all of those memos you see were not made available to the public. He made them available to me and read them all."

Morris continues that Rumsfeld was "accommodating" and "agreeable". However, he was also evasive in the extreme. "In the end, he has revealed something – but he has revealed that there may not be anything to reveal, that there may not be anything there."

This is the paradox of the documentary. It seems as if Rumsfeld is coming clean. However, he is blitzing Morris with words, documents and self-serving reminiscences. The more he reveals, the less we understand about him. The language of his memos often seems straight out of Lewis Carroll. 'Subject: what you know. There are known unknowns. There are unknown unknowns but there are also unknown knowns,' reads the memo which gave Morris his title.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

No, Morris muses, he can't separate Rumsfeld, the courteous interviewee who speaks in folksy language, saying he'll be "darned if he knows" why he agreed to talk to Morris, from the man he knows as one of the architects of the Iraq War. "I can't forget the role that he played for six years in the Bush administration. Nor can I forget the fact that he went to war under a pretext – false premises. Maybe he believed it all but that is cold comfort."

The Unknown Known is a companion piece of sorts to Morris's Oscar-winning The Fog of War (2003), about Robert McNamara, the US Defence Secretary during the Vietnam War. However, where McNamara was introspective, conscience-torn and complex, Rumsfeld is all shiny surface. Continually smiling, he has a Cheshire cat-like complacency.

Did the director like either man, I wonder. "They [McNamara and Rumsfeld] both presided over disasters. That's not to make excuses for either of them. Instead of the word 'like', I would substitute the word 'sympathetic'. Am I sympathetic to Robert McNamara? I would say the answer is yes, without condoning in any way what he did. Am I sympathetic to Rumsfeld? In the end, much, much less so. Where you would expect to find some introspection or desire to put what he has done in a larger context, it is just not there. He was hiding something. What he was hiding is that he was hiding nothing."

The Unknown Known contains intriguing insights into Rumsfeld's political manoeuvering and Machiavellianism during the 1970s, when he became the youngest Secretary of Defence in history. Like most of Morris's films, the documentary is shot with tremendous production values. At times, it plays like an episode of House of Cards, in which Kevin Spacey plays Frank Underwood, the politician on the make. Rumsfeld certainly shares Underwood's ferocious ambition – but he lacks the character's Macbeth- or Richard III-like depth.

"What is interesting about House of Cards is the wishful thinking on our behalf," Morris reflects. "We like to think there is rhyme or reason to politics, that people have thought something through, that there is some principle at stake." His experience with Rumsfeld suggests otherwise. He is a politician who, in the eyes of his critics, brought huge amounts of grief and woe into the world – and yet he isn't at all a dark or diabolical figure. "Call it whatever you want – a moral vacuity, an absence of reflection," Morris muses on the emptiness at the heart of his subject.

The documentary can't be accused of being a hatchet job. Whatever the director's own feelings about Rumsfeld, he gives the former Defence Secretary a platform to justify and explain himself at a very great length.

Morris doesn't just make films about flawed politicians. One of his most fascinating early projects, which he started in the mid-1970s, was a planned film about the real-life serial killer Ed Gein, the inspiration for everything from Psycho to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Silence of the Lambs.

Like Rumsfeld, Ed Gein was, by Morris's account, perfectly congenial company. The director interviewed him three times in the mid-1970s.

"Ed Gein only killed two people that we know of. He was notorious as a human taxidermist, grave robber, etc, etc, etc. He was absolutely pleasant, somewhat funny, perverse," Morris remembers.

I ask if Gein had seen Psycho.

"I don't believe he had seen Psycho, no," Morris replies. "He didn't go to the movies. He was in a maximum-security mental hospital for the criminally insane. It was like a joke. When I first went to see him in a place called Waupun, Wisconsin, there was a sign in front like something you would see in a horror movie saying, 'Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane'."

Morris tells a wonderful and revealing story about discussing Sigmund Freud with Gein.

"Ed was soft-spoken, actually very sweet, likable," the filmmaker recalls. "He said, 'That Freud, you know he is really so crazy'. He [Gein] was expatiating on the craziness of Sigmund Freud. He gave me an example of how crazy Freud might be. 'Freud would be walking along a street lined with buildings and balconies. You and I would be walking along that same street and we would look up and see balconies. That Freud! He would be walking along that same street. You know what he would see? He would see a woman's tits'."

The "You and I" is the key phrase here. Gein thought of himself as just a regular guy. Self-deception is a human trait shared by serial killers and politicians alike.

The Gein project stalled when the director of the mental hospital, Superintendent Schubert, decided he didn't want Morris on the premises. "Maybe I asked too many damned questions."

Morris raises the possibility that he may return to Gein at some stage. In the meantime, he has countless other projects on the boil. He may be best known as a documentary maker, but Morris also directs commercials and writes books and articles. He's about to make a fictional thriller called Holland, Michigan, which will star Naomi Watts and Breaking Bad's Bryan Cranston.

The director hopes that The Unknown Known will stick in the public mind in the same way as his earlier films have done. "It's a portrait that I believe captures something very essential. What if the ship of state is rudderless? I wanted to answer that question – why did we go to war in Iraq?" the director asks.

Morris acknowledges that his style of filmmaking has little in common with cinéma-vérité. He doesn't do grungy, fly-on-the-wall, observational filmmaking. "I was always anti-vérité," Morris says. "I've always objected to the idea that if you adopt a certain style of filmmaking, truth magically appears and that if you have a hand-held camera, use available light, etc, that is more truthful... to me, truth is a pursuit."

As a former private detective, Morris has long since realised that discovering the truth, whether in a documentary or a law case, is all about the groundwork. "I don't think it is something you can be taught explicitly. You don't go to detective school. At the heart of detective work is really talking to people and encouraging them to talk to you. There is nothing magical about it. It is hard work and creating a situation where you can learn stuff. I have always been an investigator at heart".

Screening details for 'The Unknown Known' can be found at: dogwoof.com/theunknownknown/screenings. The DVD/VOD release will be 14 July

Errol Morris: selected hits

The Thin Blue Line (1988)

Morris's study of the murder of a Dallas police officer led to the release from prison of Randall Dale Adams

A Brief History of Time (1991)

Philip Glass-scored film about the life and work of Stephen Hawking. Morris was recommended for the project by Steven Spielberg

The Fog of War (2003)

Morris won an Oscar for his story of the career of Robert S McNamara, the US Secretary of Defence during Vietnam

Tabloid (2010)

Morris was landed with another lawsuit, after Joyce McKinney, a former Miss Wyoming who was at the heart of a UK tabloid scandal in the 1970s, claimed the film defamed her

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments