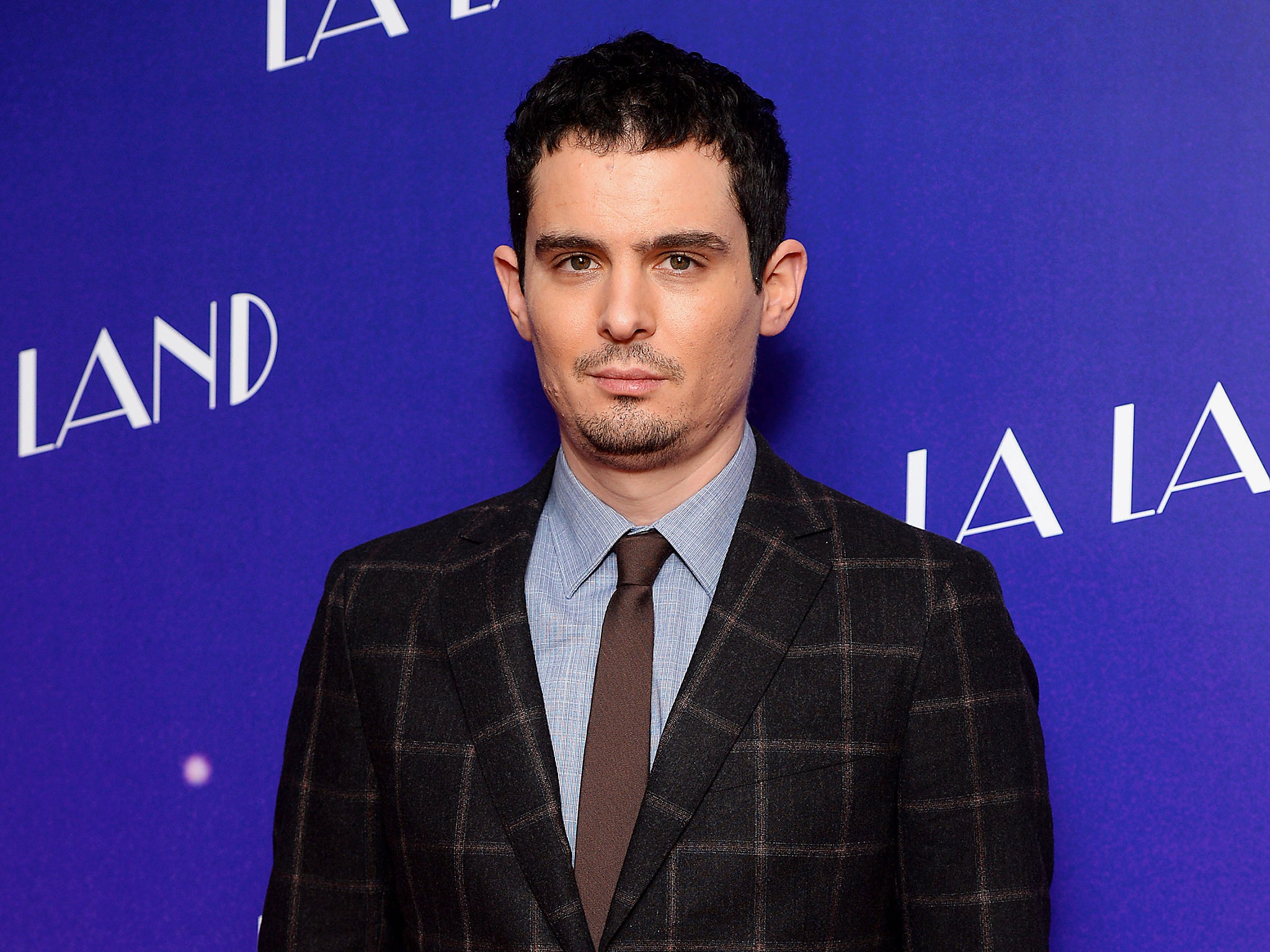

La La Land interview: Damien Chazelle on the death and rebirth of the screen musical

Why Chazelle’s film marks a unique triumph in modern cinema – striking a balance between preservation and modernity that even its own characters struggle to achieve

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For all its classic, infectiously energetic sheen, La La Land is also a film of great contradictions. Of the constant pull of opposing forces; between the commitment to those we love, and the commitment to our own dreams; between the impulse for the preservation of art, and the drive to revolutionise it.

The last of these conflicts comes to rest between two characters in particular: Ryan Gosling’s traditional jazz pianist Seb, who has a near-hysterical attachment to the old greats, and John Legend’s fellow musician Keith, who argues that jazz is an art form bred on the work of pioneers and radicals. To him, clinging to the past is to betray jazz’s evolutionary spirit.

There’s an interesting meta quality here when it comes to Damien Chazelle’s own approach to La La Land; it's clear Seb and Keith’s impassioned arguments over jazz must be close to home for the director considering he was responsible for 2015’s breakout hit Whiplash, which pits an ambitious young jazz drumming student against his ruthless teacher.

Yet, La La Land – as a take on the musical genre – seems to exist at some halfway point between Seb and Keith’s viewpoints; returning to many of the old tropes frequented during Hollywood’s Golden Age, from sound stage fantasies to montages of the city’s neon lights, while exploring a romantic relationship which feels so thoroughly modern in its beats.

“I guess it’s a little bit trying to do both,” Chazelle himself reflects when posed the question as to where on the artistic spectrum La La Land sits. “Trying to call back certain things from the past that I felt had been lost and didn’t need to be lost. But also, really, the main goal was to try and update those things. Either you try to make a case for them as still vital, or still urgent, or you try and actually change and update them, and extend that tradition in a way.”

“So it was always really important to me that the movie not be a period piece,” he continues. “And that it not be entirely in quotation marks either, that there be a modern energy to it. There’s things you can do with the camera, and things you can do with modern expectations today that you couldn’t do in the Fifties. So it was fun to take certain tropes from Fifties musicals, but put in them in a modern city and film them in a modern way, and see what results from that.”

Indeed, La La Land does boldly wear its influences on its sleeve, with fans of the genre easily picking out nods and references to some of the greatest classics in the genre. For example, the work of Arthur Freed, the lyricist who worked with MGM on creating the likes of An American in Paris and Singin’ in the Rain, and helped to shape the careers of Gene Kelly, Frank Sinatra, Cyd Charisse, and countless others. The French answer to the American musical boom, too; specifically in the work of Jacques Demy and his beloved films The Umbrellas of Cherbourg and The Young Girls of Rochefort.

It was a moment in cinematic history that feels so self-contained now, with the screen musical having been almost wiped out by the Seventies shift to realism and the birth of the blockbuster. “I think audiences really want stuff that feels real,” Chazelle reflects. “And since the Seventies have kind of decided that verisimilitude or reality – a more literal reproduction of reality – is what they want from movies. Whereas, I think in Old Hollywood, there was a lot more bandwidth allowed to have, like, obviously painted sets and people talking a little more differently than people in real life talk. And the whole old fashioned idea of movie stars was its own thing.”

“I think musicals fit into that vision of cinema as not having to be so literally reflective of real life. Musicals require a certain suspension of disbelief,” he continues. “And now that’s just, kind of, out of favour. You don’t have any fewer movies about people playing music than you did in the Forties or Fifties, but you have far fewer movies where people actually break the fourth wall or break the diegesis and break into song. There’s just not as much of a willingness to go along with that jump.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Indeed, though musicals are still fairly regularly making it back to screen, they tend to largely conform to faithful adaptations of hit Broadway productions; though it’s perhaps telling that Tom Hooper’s 2012 version of Les Misérables tried so hard to break from its illusionary confines and deliver a musical that felt ‘real’.

“I think a lot of that is just kind of a by-product also of Hollywood right now,” Chazelle adds. “Anything original is kind of difficult to get off the ground. And, I think, when you take something like the musical that feels always a little iffy to people financially right now, it really helps to have it be based on a pre-existing hit or property. And, you know, some of those movies are great; but what you wind up losing is that idea, that used to be somewhat commonplace, of music and musicals conceived directly for the screen. And I think that’s just a different thing, it yields a different result when they’re really conceived completely in unison; like the Jacques Demy movies.”

Traditionalist in one manner, yet modernist in another; Chazelle’s search for the “modern energy” of the musical finds its perfect moment in the ballad sung by Emma Stone’s Mia, an actress who finds herself in the most crucial audition of her life, but one where she’s finally allowed to flourish. The usual spectacle of the musical fades into darkness; as the camera fixates itself solely on Mia, and on Stone’s own floor-to-ceiling-windows-to-the-soul kind of eyes.

“It’s a moment where her character becomes herself in a way,” Chazelle says of the scene. “In previous auditions, and in a lot of previous parts of the movie, she’s spent so much time figuring out who she is or playing other parts even without realising. So this had to be the moment where everything got distilled into one pure idea.”

“So the visuals of it were stemming from that idea, and trying to call back also to earlier moments in the movie where we’d done this sort of light gag, just that simple idea of the room going darker and everything dissolving into a spotlight. That it represented some kind of a journey to one’s self. So I think the idea here was to have the audition number be a climax for that and have everything else really fade away and fall away, and you’re just left with her.”

“It’s the first time where there’s a number where she’s not in some crazy Technicolor dress, she’s not made up in the Old Hollywood way and the camera’s not doing a bunch of crazy things. There’s a certain simplicity and unvarnished texture to it that was important.”

La La Land, in its own way, still seeks the veracity that has so fixated cinematic audiences in the past few decades; but in a kind of emotional truth that can still sit happily side-by-side with the film’s nostalgic fantasies. Seb and Mia, for example, aren’t played by seasoned Broadway performers with perfectly trained vocal chords and years of tap experience, but by two of the most emotionally immediate actors in Hollywood.

“At the end of the day, I wanted everything to remain really human in the movie,” Chazelle says. “Never to let the numbers become purely technical execution of steps; it’s one thing that I think they were really good at, and it’s partly why I wanted actors and not professional dancers or singers. I wanted them to approach those things as actors, as everything coming from the character and the idiosyncrasies of the character; never favouring technique over character or story.”

Yet, there’s still a little Old Hollywood to Stone and Gosling here, with La La Land marking the third time the pair have starred as an onscreen couple, following 2011’s Crazy, Stupid, Love and 2013’s Gangster Squad; incidentally mimicking the likes of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, or Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy.

“There’s this Old Hollywood idea of the recurring couple that I really liked,” Chazelle says. “So, I think with Ryan and Emma it was fun, especially with a musical, to take a couple that we’re somewhat familiar with as a couple but put them in a very unfamiliar world; unfamiliar for them, unfamiliar for a lot of audiences right now as well, I think.”

“So they provide a kind of access point, because, even if we haven’t seen the movies they’ve done before, we have this kind of sense with them immediately that they’re meant to be a couple onscreen. That was something certainly that the Old Hollywood movies had; those movies would always start out before the couple becomes a couple and you’d always have a sense that the music’s going to bring them together.”

A harmonious marriage between old and new, between preservation and modernism; La La Land is a unique triumph in modern cinema. We may have long travelled past the musical’s Golden Age heyday, but there’s still hope: with the film’s impressive box office performance in the US and accelerating awards glory, maybe Chazelle’s actually cracked it – and the Hollywood screen musical can finally experience its rebirth.

‘La La Land’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments