Blade Runner and the Beat Generation: The missing link that gave the famous film its title

‘Blade Runner 2049’ is the long-awaited sequel to one of the most critically acclaimed science fiction movies of all time. But where did it gets its name from anyway? And what does it have to do with the Godfather of Beatniks William S Burroughs? David Barnett finds out

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The author Philip K Dick was the master of the high-concept science fiction story. Indeed, his novels and short fiction have provided fertile ground for Hollywood and TV, and never more so than right now.

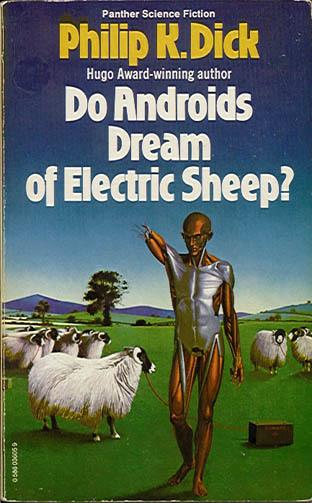

Blade Runner 2049, the sequel to 1982’s Blade Runner, might not be directly based on a Dick story, but then the original movie was only loosely based on his 1968 novel Do Android’s Dream of Electric Sheep? anyway.

“Loosely adapted” is the key phrase when dealing with Dick adaptations. The current series of one-off dramas, Electric Dreams, which Channel 4 is broadcasting on Sunday nights, riff off Dick’s short stories. Total Recall, the original 1990 movie starring Arnold Schwarzenegger and the 2012 remake with Colin Farrell, were both based on We Can Remember It for You Wholesale. Amazon’s The Man in the High Castle takes Dick’s original concept – what if the Allies lost the war and the US was occupied by Germany and Japan – and has expanded it to two seasons’ worth of TV.

Dick, who was born in 1928, died in March 1982, just three months before Blade Runner – directed by Ridley Scott and starring Harrison Ford as Deckard, hunter of rogue “replicants”, or biologically-engineered artificial humans – was released in cinemas.

He never saw the movie in its entirety, just excerpts, and in October 1981 he wrote a letter to the production company in which he said, “The impact of Blade Runner is simply going to be overwhelming, both on the public and on creative people, and I believe on science fiction as a field…This is not escapism; it is super-realism, so gritty and detailed and authentic and goddam convincing that, well after the segment [that Dick saw] I found my normal present-day reality pallid by comparison.”

It seems that Dick had no beef with the fact Blade Runner was not a faithful adaptation of his novel. Nor have other movies been, such as Minority Report, The Adjustment Bureau, Screamers. His imagination was boundless but his execution did not render his novels or short stories in Hollywood-friendly formats. So it is unsurprising, and not really an insult to Dick, that adaptations of his work have taken his central concept and run with it rather than faithfully following the narrative.

One question has perhaps bugged fans since Blade Runner’s release 35 years ago, though… why “Blade Runner”? It’s not a phrase used in the book and it doesn’t really make much sense in the context of the movie. Deckard doesn’t “retire” (in the parlance of the film) the replicants he hunts with knives, nobody is illegally transporting swords anywhere. It’s simply a throwaway slang term for cops who hunt replicants, added in to the script to let the title make sense. So where did it come from?

The answer is from a relatively obscure (though well respected) science fiction author, Alan Nourse, by way of none other than William S Burroughs, the grand old man of American Beat letters and author of Naked Lunch and Junky.

Nourse first. He was born in 1928, the same year as Dick, and died a decade after him. He began his writing career in the early 1950s, penning a number of short stories for the science fiction pulp magazine Galaxy, followed by a series of novels for both juveniles and adults; Trouble on Titan (1954) was his first, and a dozen more followed.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

But Nourse was also a trained doctor, and practised as a GP in Washington state from 1958 to 1963, alongside his writing career. After he retired from medicine, he wrote a “Family Doctor” column in Good Housekeeping magazine, and also wrote a slew of non-fiction books wth titles such as So You Want To Be a Doctor?, Teen Guide To Safe Sex, and – under the pseudonym Doctor X – Intern, a frank “inside account” of the day-to-day life of a junior doctor.

Where Nourse’s science fiction and medical interests crossed over was in novels such as 1959’s Star Surgeon and, most importantly, in a 1974 novel called The Bladerunner.

The Bladerunner posited a dystopian future society that was actually worthy of Philip K Dick. Free medical care is available to all… so long as they abide by a set of Eugenics Laws, which includes sterilisation. Those who do not comply have to seek underground medical care from rogue doctors, and the protagonist of the novel, Billy Gimp, illegally transports medical supplies to these off-the-radar doctors, including of course, scalpels… making him the titular Bladerunner.

The Bladerunner might have passed into relative obscurity along with Nourse’s other science fiction novels, but for it coming to the attention in the mid-Seventies of William S Burroughs.

Then in his 60s, Burroughs had already achieved fame and notoriety both as an author renowned for experimental, edgy works of his own, and as a “character” in the Beat Generation of the 1950s, appearing in many of Jack Kerouac’s works under various pseudonyms. He wrote semi-autobiographical works such as Junky, about the downbeat life of a heroin addict, the controversial Naked Lunch, and the Nova Trilogy using the “cut-up method” he developed with collaborator Bryon Gysin, using lines literally sliced from other texts and reassembled in a random order.

In late 1976, Burroughs’s assistant James Grauerholz wrote to the writer’s agent to say, “William has recently read a novel called The Bladerunner, by Alan E Nourse…William liked the book very much and in fact has begun to consider a film treatment for it; he’s written some twenty pages.”

Burroughs obtained the film rights from Nourse and completed the screenplay, but it was never made. Instead, Burroughs published it in 1979 under the title: Blade Runner: A Movie, and it joined the ranks of Burroughs minor works, one for completists only.

It was around this time that work was beginning on the adaptation of Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, a title that just wasn’t going to wash with Hollywood. Hampton Francher was the man brought in to draft the first treatments of the script, and was working under a couple of potential titles; Android was one, Dangerous Days another. Director Ridley Scott wasn’t taken with either of them.

In a 1982 interview with Film Comment magazine, Scott recalled when inspiration struck. He said, “In about the fifth draft of the script, the phrase ‘blade runner’ popped up. I thought, Christ, that’s terrific. Well, the writer looked guilty and said, ‘As a matter of fact it’s not my phrase, I took it from a William Burroughs book’.”

So the book was tracked down and Scott bought the rights to use the title Blade Runner, apparently for just $5,000.

The movie that followed became a classic, and 35 years on it has a new lease of life thanks to the sequel, Blade Runner 2049. It’s nothing to do with Alan Nourse’s original novel; it’s nothing to do with William S Burroughs’ vision of what that novel could be filmed like. And it’s perhaps only loosely anything to do with Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?.

The term “Blade Runner” is enmeshed in modern parlance now, but it’s interesting to see how it arose, the piecemeal way in which it found its way to be the movie’s title, from a series of seemingly unconnected events and random moments. Moments, as someone once said, lost in time, like tears in the rain…

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments