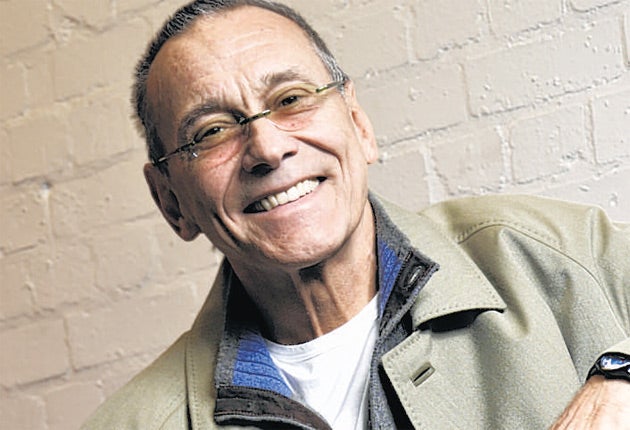

Andrei Konchalovsky - The roots and rarities of a man of two worlds

Andrei Konchalovsky is famed for his US genre films but his Russian work best represents him, argues Geoffrey Macnab

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The film-maker Andrei Konchalovsky, whose career is celebrated at London's Barbican this month, recently showed an unexpected guest round an exhibition of his grandfather Petr Konchalovsky's paintings in Moscow. The guest, who turned up on the very last day of the exhibition, was the Russian Prime Minister Vladimir V Putin. The invitation had been issued to Putin by Konchalovsky's brother, the Oscar-winning director Nikita Mikhalkov. When the Prime Minister finally accepted, Konchalovsky felt that he needed to be there too. After all, he is Chairman of the Petr Konchalovsky Foundation and more of an expert in his father's work than his brother.

Thus it was that Konchalovsky found himself in the unlikely position of wandering round the Tretyakov Gallery, discussing his grandfather's links with Picasso and Cezanne with Mr Putin. He describes the Prime Minister as "shrewd" and intelligent.

Konchalovsky is best known in the West for his Hollywood movies, such as Runaway Train, starring Jon Voight, and Tango and Cash, with Sylvester Stallone and Kurt Russell, but he has impeccable Russian establishment credentials too. His father Sergei Mikhalkov (1913-2009) wrote the country's national anthem and was decorated by Putin with the Order for Service to the Fatherland 2nd Class in 2003. He is very distantly related to Leo Tolstoy. Not that this means he is a fervent believer in the new Russia. Ask him about the imprisoned Russian oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who recently received a new 14-year sentence for embezzlement and money laundering, and Konchalovsky declares the oligarch "should not be in jail," adding that if Khodorkovsky is behind bars, there are others who should be there with him.

For his opinions on recent events in Russia, he refers to his articles for the website openDemocracy. In "Russia: Land of the Mob", written in response to last November's mobster killings of 12 people in the Cossack village of Kushchevskaya, he argues that Russia, "a society with no real citizens, no understanding of personal responsibility to one's country; a society dominated by peasant consciousness where loyalties are limited to the realm of the family and where everything outside the family circle is regarded as in in some way inimical, can have no law."

The Russian director also explains that his world view is the opposite of that of his equally celebrated brother, Nikita Mikhalkov, who is nationalistic, conservative and recently published a 10,000-word political manifesto of "Enlightened Conservatism" advocating strong leadership to guide Russia along its "special path".

Konchalovsky, who originally planned to be a pianist before meeting the film-maker Andrei Tarkovsky (with whom he scripted Andrei Rublev) and turning toward cinema instead, clearly feels ambivalent about his privileged upbringing. "You know, whatever I achieved in my life, it was always interpreted that my father helped me. It was an easy way to explain everything I did." He adds that the "intelligentsia doesn't like our family".

There still appears to be an animus against the director and his brother in certain quarters in both East and West. Over the last year, both Konchalovsky and Mikhalkov have released huge-budget films that, for different reasons have flopped. Burnt by the Sun 2, Mikhalkov's $55m sequel to his 1994 Oscar-winner, was excoriated by Russian critics on its release last year and sunk at the box-office. A rousing war film in the vein of Elem Klimov's Come and See (1985), it suffered with audiences and critics because its director was perceived to be too close to Putin and the Russian leadership.

Konchalovsky's 3D version of The Nutcracker, starring Elle Fanning and John Turturro, opened in the US before Christmas and was even more viciously attacked by American critics. "The film cost $90m and has yet to gross $300,000 worldwide, making it perhaps the biggest flop of all time," The Huffington Post suggested. Konchalovsky admits he was "astonished by the venom" in the reviews, especially that of Roger Ebert, who seemed appalled that the rats wore "fascistic uniforms" and that a film aimed at kids made reference to the Holocaust. "The Nutcracker in 3D is one of those rare holiday movies that may send children screaming under their seats," he wrote. The director argues that these critics didn't realise that E T A Hoffman's original story, "The Nutcracker and the Mouse King", was itself dark – they were more used to the Tchaikovsky music than the source material.

This isn't the first time that Konchalovsky has seen one of his movies attacked. His second feature, Asya's Happiness (1966), received an equally vicious response, this time from the Soviet authorities themselves. His sin, in their eyes, was to have depicted life on a collective farm in a realist, non-propagandistic way. Only three of the cast members were professionals. The rest were real farmers. This was, as its opening intertitles explain, "The story of Asya Klyachina who loved a man but did not marry him." The film wasn't overtly political. However, Konchalovsky didn't just show happy workers tilling the fields. He touched on his protagonists' yearnings, and made it clear how unhappy their lives often were. There are references to the Vietnam war. In one scene, a former Gulag prisoner talks about his homecoming and his fraught reunion with the wife. Beautifully shot in black-and-white, the film has a spontaneity and lyricism that you don't expect to find in a Soviet film set on a collective farm.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

The censors made him "cut and cut" Asya's Happiness. Even so, the movie was put on the shelf and only properly screened in the Glasnost era of the late 1980s. The former President Mikhail Gorbachev called it one of his favourites.

Konchalovsky, who moved to the US in 1980, has experience of dealing with Soviet-era censors, and of working within the Hollywood system. He had ferocious battles in both places. "In an ideological censorship state, you know what you cannot touch and the rest is completely up to you. You can fool the state till the stage the film is made. That means the film is made and then it is maybe banned – but you made it!" On the differences between working in the two film cultures, he says: "Let's put it this way – it's much more difficult to fool certain producers than it is to fool the state."

He points out that from Michelangelo to Tolstoy, what we consider to be masterpieces were often created against a backcloth of censorship. "Personally, I think the audience creates masterpieces, not freedom."

What is clear is that not many of the films Konchalovsky has made in the West have matched the delicacy and artistry of Asya's Happiness or his brilliant 1970 adaptation of Uncle Vanya. The latter film, screening in the Barbican season, is stagy but cinematic at the same time, full of long tracking shots and slow pans. "After I made Uncle Vanya, I realized that I can make a film in any limited space, even in an elevator," the director quipped. "It would be enough to analyse the infinity of a human soul."

In Vanya, Konchalovsky hones in on the faces not of the actors who are talking but of those who are listening. Every expression and gesture is registered. The characters' sense of romantic longing, and of their disappointment at the direction their lives has taken them in, is always evident.

"Probably the best filmed Chekhov I've ever seen," Vincent Canby wrote in The New York Times, calling the film "an exceedingly graceful, beautifully acted production." Woody Allen said that he didn't think "there could be a more perfect rendering of the play".

Such reviews stand in stark contrast to the brickbats that have been levelled at Konchalovsky since the release of The Nutcracker. The Barbican's Directorspective isn't exhaustive, but it hints at the range and artistry of a film-maker whose best Russian work is hardly even seen in the West.

'Konchalovsky: the Directorspective', Barbican Centre, London EC2 (020 7638 8891) to 30 January

Doubling up: the best of Konchalovsky

Tango and Cash (1989)

Konchalovsky is reported to have had a difficult time helming this buddy movie, which stars Sylvester Stallone and Kurt Russell. It is genre fare, worlds removed from 'Andrei Rublev', which Konchalovsky co-scripted with Tarkovsky, and 'Asya's Happiness'. However, as far as cheesy action movies go, it's also very entertaining, and it underlined the director's adaptability. He could run the gamut from Soviet realism to muscular Hollywood star vehicles.

Asya's Happiness (1966)

Konchalovsky's best-known Russian film is set on a collective farm. Its humour and lyricism belie the idea that it is propaganda – and go a long way to explaining why the Soviet authorities were so unhappy about it. The mid to late 1960s was the era of a new wave in European cinema. 'Asya's Happiness' stands as a Russian counterpart to the equally personal films made by Czech directors such as Milos Forman and Jiri Menzel; and, indeed, by Ken Loach in Britain.

Runaway Train (1985)

A top-notch action movie with a relentless narrative drive, Konchalovsky's film was based on a screenplay by Akira Kurosawa. Jon Voight stars as a convict on an out-of-control train. The director doesn't just emphasise speed, danger and spectacle, he also pays attention to psychology. This is a character study as well as a white-knuckle ride.

Uncle Vanya (1971)

The British have a terrible tendency to make Chekhov's great play seem like an Edwardian drawing-room comedy. There is nothing twee or affected about this exemplary Russian adaptation. Konchalovsky hones in on the decadence and disaffection of the Russian characters on their country estate. They're cultured and sophisticated but their sense of disappointment in their lives and foreboding about the future is always very evident.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments