Eight Days A Week: Oscar winner Ron Howard on his revelational new documentary about The Beatles’ brief-but-intense touring years

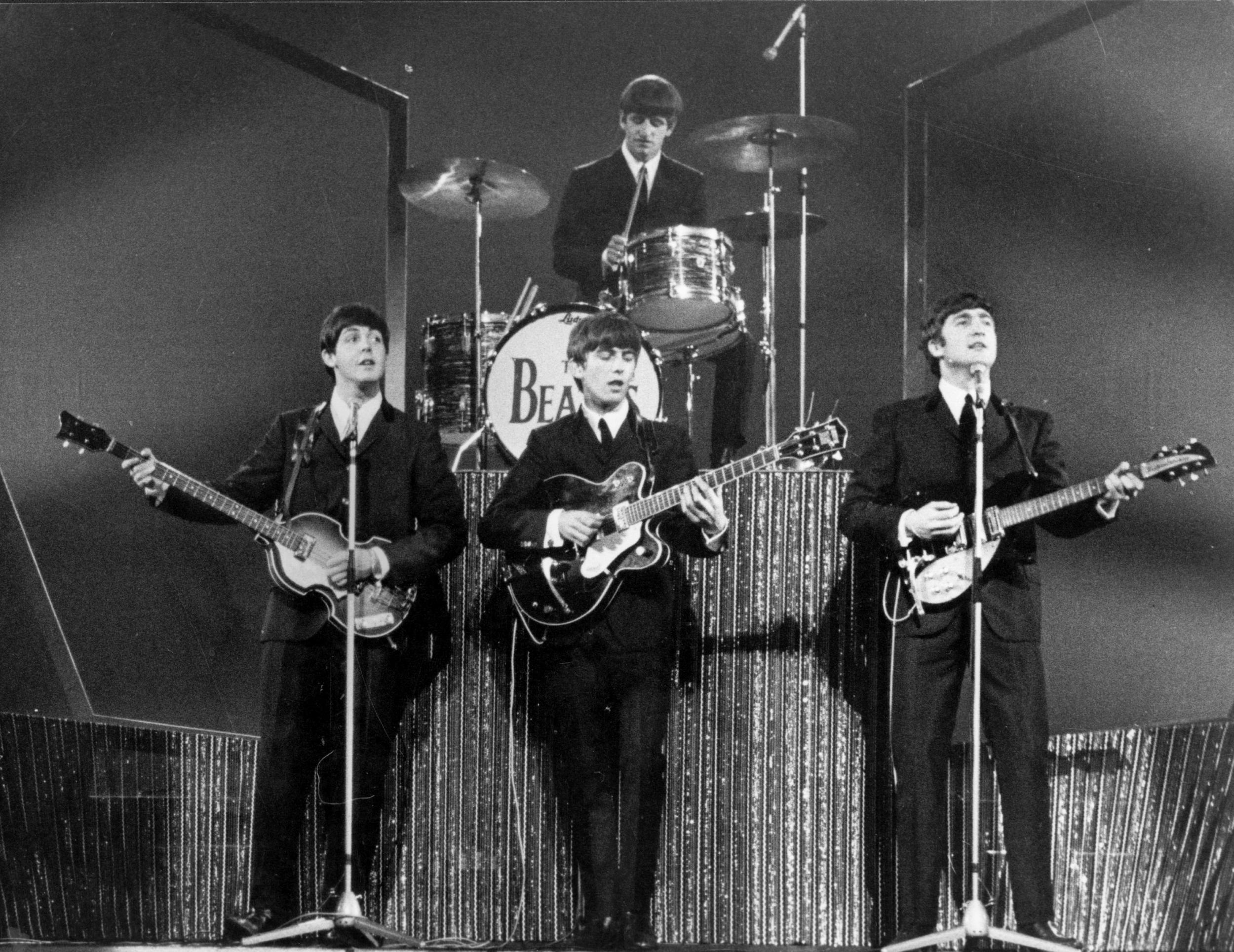

The film is compiled around a wealth of original footage, culled from private collections, media organisations and the vaults of The Fab Four’s own Apple Corps

Ron Howard knows about pressure. The director/producer’s work slate is full and varied, and permanently so. Only nine months ago In the Heart Of The Sea, his blockbuster retelling of the origins tale of Moby Dick, was in cinemas. Next month sees the appearance in cinemas of Inferno, his third adaptation of Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code novels, with Tom Hanks reprising his lead role.

It’s followed by the TV broadcast of the mini-series Mars, an innovative and epic sci-fact production for National Geographic that mixes future drama with contemporary documentary footage. Howard is a producer on the series, as he is on another upcoming small screen project, a series of dramas about the life of Albert Einstein.

Who better, then, than the onetime child actor (most famously he was Richie Cunningham on Seventies/Eighties sitcom Happy Days) to direct The Beatles: Eight Days A Week, a revelational new documentary about the band’s brief-but-intense, super-pressurised touring years?

“If there’s anything I was most inspired by in working on the movie,” begins the hugely affable Howard, “it was coming to understand and recognise that creative growth was going on while they the band were under such pressure as performers and as celebrities and symbols of change. It’s pretty mind-blowing that they could sustain that creative growth,” he says, noting the boldness and adventure the perennially-touring band still managed to bring to albums such as Revolver and Rubber Soul.

Eight Days A Week is compiled around a wealth of original footage, culled from private collections, media organisations and the vaults of the Fab Four’s own Apple Corps. These are rounded out by new interviews with Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr and archive interviews with George Harrison and John Lennon. The challenge for the feature filmmaker: how to craft a fresh story from pre-existing material, especially when it’s a tale so often already told.

“It’s fascinating, and it’s kind of a double-edged sword,” acknowledges the 62-year-old Oscar-winner (for 2001’s A Beautiful Mind). “On the one hand, creatively it’s good to have some limitations. So the challenge for me was: could I look at it, analyse, talk about it, analyse it again, then present what I would like to be able to say if I were shooting from scratch?

“And in a lot of instances the answer was yes, but in other instances the answer was no. So you think: OK, is there another way to express this idea? That’s where interviews come in, and trying to create some [social and cultural] context around the images that we do have.”

Still, there was the promise of undiscovered gold. One woman approached the filmmakers with footage she had from The Beatles’ final public concert, the 1966 show at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. It had apparently lain under her bed, unviewed, ever since.

“That was one of the enticements for me – there was some new and interesting footage. And that [particular discovery] was a hallelujah moment for the Apple people. That kind of footage became a good foundation, a good building block.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“I also believed – and it turned out to be true – that by being able to apply cutting-edge technology and digitally enhance some of these images, you’re just able to get a lot more detail out of them. I wanted to keep looking at the story through the prism of the guys; this ensemble on this adventure together. They are individuals yet there’s a brotherhood, a collective psyche at work. So we could re-edit some of the performance moments that we’ve seen before but in a way that reflects an idea that we’re trying to express, to make this story as specific and fresh and involving as possible.”

One of Howard’s achievements is to make the differing personalities within the group pop out. We see Harrison, the youngest member of the band, tire most quickly of the chaotic circus that Beatles touring rapidly became. We see Lennon wrestle with the conflicting pressures of being true to his self (his sarky, acerbic self) and keeping the show on the road – most infamously in the “bigger than Jesus” kerfuffle. It’s one of the achievements of Eight Days A Week that we see exactly how mortally dangerous that “kerfuffle” was when The Beatles came to play the more God-fearing corners of the United States.

When I interviewed Starr last year, I asked what it was like for his mum when her son’s band blew up all over the world. Was she worried about what Beatlemania would do to her darling boy?

“No, no, she loved it,” Starr replied. “And she did love me every second of my life. And the other side of the coin was, I called her in ’66 to say: ‘We’ve stopped touring now. We’re not gonna tour any more, mum.’ ‘Oh, but you’ll be playing Liverpool though, won’t you?’ ‘No, no – were not playing live any more!’ And she couldn’t understand that.”

In counterpoint, Eight Days A Week also reveals McCartney’s hunger for touring, certainly in the early days. Speaking to him in 2013, I asked him why he was, still, on the road in his seventies. He replied that the desire to perform was built into him, from Hamburg dives to American stadiums via some 249 shows at Liverpool’s Cavern.

“It’s that tipping point thing, isn’t it, 10,000 hours?” McCartney told me, a reference to Malcolm Gladwell’s theory about true masters of their art requiring that many hours of practise. “I think there’s a bit of that to it, yeah. It’s all I’ve ever done, in one respect. It’s like I’ve always just worked in that factory, and I kinda like it. It’s home.”

“It’s hardwired in him,” agrees Howard. “Also, he loves performing. Paul’s a true performer; he’s a great writer; a great musician; great in the studio. I’ve talked to people who’ve worked with him over the years – one described Paul as the greatest bandmate you could ever have.

“But I also believe that all along he felt there was right way and a wrong way to do things. And he would not rest until the idea was fulfilled in what he felt was the right way. He brought that to the band, and continued with it throughout the rest of his career.”

In terms of doing things the right way, Howard reveals that McCartney made one key request to the filmmaker. It pertained to his late writing partner and the decades of rumour and counter-rumour that shadowed their relationship.

“This was the big thing that Paul asked me – he said: ‘You know there was a lot that happened later that kinda got in the way of John’s and my friendship. But when we’re talking about this period of time, this was a period of friendship, and I really hope the movie reflects that.’ That was his only request. And then he was happy to talk about a bit of that in his interview.”

The Beatles: Eight Days A Week is in cinemas now

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies