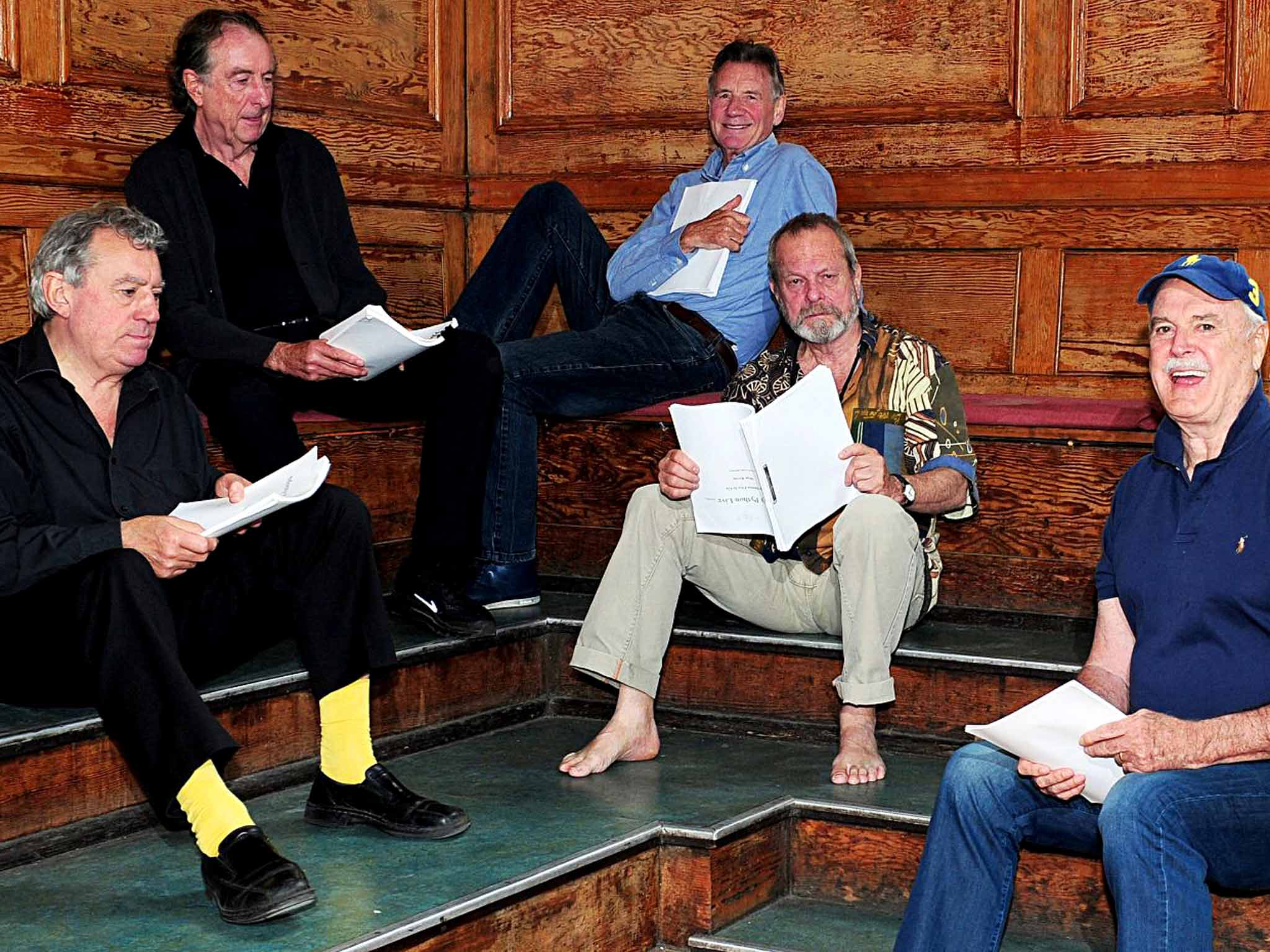

Monty Python: The last laugh?

The Monty Python reunion shows which begin next week sold out within a minute. Then the backlash began. So is this the glorious farewell of a comedy institution? Or a cynical, greedy stunt? Both, Eric Idle tells Paul Hoggart

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Monty Python team got into hot water over their 1979 life of Jesus spoof, Life of Brian. Now, though, they might reflect ruefully on Christ's words that "a prophet is not without honour, except in his own country". None of the five surviving Pythons would describe themselves as prophets. But they can't have failed to notice a distinct lack of honour in the British press about their much-publicised reunion show.

One critic blasted: "Rock bands, such as the Rolling Stones, may feel they can get away with touring songs about pulling teenaged chicks when they are well into their 60s and 70s, but the Pythons should be sharp enough to know better." Nonetheless, "Monty Python Live (Mostly)" opens in the London Arena next week and runs for 10 more nights. The final performance will be screened live in cinemas around the world, including 500 in America. Tickets for the first performance sold out in a record 43.5 seconds, but the enthusiasm of fans has not prevented a distinctly negative narrative from emerging.

As soon as the show was announced, reports abounded that the gang was doing it only for the money, in particular to recoup legal bills after losing a court case last year over royalties for Eric Idle's stage musical, Spamalot. Apparently their long-standing musical collaborator, Neil Innes, was also considering suing the Pythons for unpaid royalties (though this was neither followed up nor corroborated).

A lacklustre press conference to announce the event, in which the five Pythons seemed to radiate mild boredom, didn't help. A chat show appearance to promote the show, in which John Cleese poured his drink over the host and ended up slowly flicking cocktail nibbles at him, added a bizarre twist to the pre-publicity. Even odder, Michael Palin confessed that "a lot of Python was crap", adding: "We put stuff in there that was not really that good, but fortunately there were a couple of things that everyone remembers, while they've forgotten the dross."

Terry Gilliam, the artist, film and now opera director, may have added to this dismal mood music. He called the thought of the reunion "depressing" and questioned the Pythons' sharpness and the relevance of their humour now that they themselves have become "establishment" figures.

Others have been asking if the Pythons were ever that funny. This dismissive spirit is summed up in a sideswipe by the columnist Peter Hitchens: "I never wanted to have any human rights," he wrote when the show was announced, "but surely the planned revival of Monty Python violates every single one of them." Hitchens insists that this was a joke, but his attitude raises uncomfortable questions even for those of us who became avid teenage fans in 1969 when the team forced its way into popular consciousness with bizarre sketches about flying sheep and a superhero who turns into a bicycle repairman "whenever bicycles are threatened by international Communism".

Hitchens has picked up on a more general Python-sceptic strand. "The attraction of much of it, like Beatles music, is a mystery to many, not just me," he tells me. Python-unbelief dates back to the show's heyday. Richard Ingrams, the founder of Private Eye, needled Cleese with his scathing criticism, leading to Cleese using Ingrams's name for a guest caught inflating a plastic sex doll in Fawlty Towers.

So is this just a money-spinning stunt by a bunch of cash-strapped, superannuated has-beens who don't really want to do it? Has their wacky form of humour, like Cleese's dead parrot, expired and gone to meet its maker? Has the team rung down the curtain and joined the choir invisible? Should this be an ex-sketch show? The Pythons are in all in their seventies now. Are they capable of recapturing the old magic – and was the humour really as magical as all that?

First broadcast on the BBC in 1969, Monty Python's Flying Circus ran for three seasons under its original title, clocking up 39 episodes, each packed with zany sketches loosely linked by Gilliam's surreal animations. A fourth series of six episodes, called Monty Python and sans Cleese, aired in 1974. The team's first feature film, sketches collated under their catchphrase And Now for Something Completely Different, was released in 1971. After the TV show finished its run, the team reassembled in 1975 to make a low-budget Arthurian spoof, Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Monty Python's Life of Brian came next, in 1979, and stirred up great controversy. 39 local authorities banned it as blasphemous. In New York, cinemas were picketed by protesting rabbis and nuns. Their last film, Monty Python's The Meaning of Life, a collection of new sketches and songs, was released in 1983 and included such gross moments as Mr Creosote, a monstrous glutton played by Terry Jones, eating so much that he explodes.

Between 1976 and 1981, members of the troupe appeared in shows for Amnesty International, known collectively as The Secret Policeman's Ball. Their last stage performance as an ensemble came in 1980, recorded in the 1982 movie Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl, and the last time the whole team appeared together in public (minus Graham Chapman, who died of throat cancer in 1989) was 25 years ago, in an interview with sketches hosted by Robert Klein at the US Comedy Arts Festival.

The job of coordinating and constructing the latest – and perhaps final – Python show has fallen to Idle, famous among Python devotees as the insinuating, sex-obsessed stranger in the pub. His "nudge, nudge, wink, wink, say no more!" quickly became a national catchphrase. Idle also created the drunken philosophers' song (the witty ditty in which the great thinkers of world history are all characterised as drunks: "There's nothing Nietzsche couldn't teach ya 'bout the raising of the wrist / Socrates himself was permanently pissed") and the insanely chirpy "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life", sung by the massed chorus of crucifixion victims at the end of Life of Brian.

Idle is defiant. "I never read the British press," he tells me from his office in Los Angeles. "They're bonkers."

No one disputes that the motive for the reunion is financial, although accounts of the nature of the Pythons' problems have varied. Veteran comedy writer Barry Cryer, known to the Pythons as "Uncle Baz", was the warm-up man for their first show, and he has remained friends with the team ever since. "You hear conflicting stories from them," he says. "Dear Mike Palin says, 'We need the money', and Terry Jones says, 'I'm paying off my mortgage'. John Cleese has his alimony to pay." Cryer is referring to Cleese's acrimonious 2009 divorce from his third blond American wife, Alyce Faye Eichelberger. The settlement reportedly cost him $13m. Jones's financial difficulties also arise indirectly from the break-up of a marriage, as he took on a heavy mortgage after divorcing his wife of 42 years to marry Anna Soderstrom, a Swede 41 years his junior.

Idle is unambiguous and forthright. "Of course it's for the fucking money!" he says. "It's to clear off a legal debt [the legal costs incurred by the Spamalot case], so of course that's true. But only in England would they pretend you should be doing a show for nothing. Nobody in show business works for nothing."

The idea for a final Python show came up when Idle consulted his friend Jim Beach, the band manager of Queen. "He told us if we did a night at O2 we could clear all this [debt]," says Idle. "Suddenly, a boring business discussion became a creative meeting, and everybody got very excited," he adds. "It was that simple. When we decided to do it, everybody got very happy. It is a wonderful thing. To be able to get together with old friends from 50 years ago and do Python for a last time, to come out, perform it, send it round the world and say, 'That's it. That's the final night', I think that's tremendously fortunate. Nobody has the opportunity to do that in show business. You never know it's your last night."

When ageing musicians give concerts, they usually have to balance their fans' desire to hear their greatest hits with their own wish to play new material. This has not been a problem for Idle, who tells me he has spent nine months writing the script. "There's no new material," he says, "but there are new ways of doing things, and there are sketches we've never done live before. You can't write better Python sketches than the best of Python. Nobody could, because they get better in memory. It's the cream of the material, and the others are saying how happy they are with it."

The innovations, it seems, have all come in new forms of presentation. Idle says the set design, by Gilliam, will be "like a necklace with the sketches as the pearls. The main secret is [choreographer] Arlene Phillips. We've got beautiful young singers and dancers, including lots of hot girls. There'll be a lot of energy onstage. Musical revue is a classic old form. I've called it 'Déjà Revue'. It's got a lot of surprises."

Some critics claim that, apart from Gilliam's extraordinary graphic links, little of their material was ever particularly original, though the Pythons have never made the claim of originality. Two shows are regularly cited as influences, along with their spin-offs. The Goon Show, the radio comedy starring Peter Sellers that ran for nearly 10 years through the 1950s, included material as anarchic, surreal and just plain daft as anything dreamed up by the Pythons. The other great influence on the Pythons was the 1960 stage revue Beyond the Fringe, starring Peter Cook and Jonathan Miller from Cambridge University alongside Alan Bennett and Dudley Moore from Oxford. It was not just the political satire in Beyond the Fringe that cut deep. The show ruthlessly satirised British stereotypes, usually from the professional middle classes: politicians, military officers and clergymen.

Python arrived on the crest of a wave of disrespect for such risible authority figures, but widened the range of targets with pokes at pompous lawyers, civil servants, schoolmasters and chartered accountants (a trade Cleese's father had encouraged him to pursue).

Hitchens sees this lack of deference to respectable members of the community as part of the problem with the Pythons. "Irreverence has been supposed, since about 1963, to be a virtue," he tells me. "Is it? What about conformist irreverence, directed against manners, customs and institutions that are actually valuable?"

Attitudes towards this vary with the individual Pythons. According to Cryer: "Michael Palin always said about Python, 'We weren't trying to change anything'. There was no arrogance there. They just said, 'We'll do what we think is funny and hope other people like it'."

Railing against authority was just part of the Pythons' shtick. The new freedoms of the Sixties and Seventies "all had to be fought for", says Idle, "and the ground was reluctantly given up. We used to really upset the middle classes – épater la bourgeoisie. Women would scream at us, 'I hate you lot!' People see us as cuddly and soft now, but I miss really upsetting the middle classes. I hope we can still be a bit disgusting."

Over the years, the Pythons have repeatedly acknowledged their debt to the diverse comedians and comic traditions that fed into their humour. They have also confirmed that their willingness to show naked women's breasts helped attract cohorts of adolescent boys in a pre-internet porn era. Certainly, they were the first show to bring newer comic styles to a prime-time audience.

"There are certain shows that seem like watersheds," says Cryer, and it may have had a lot to do with the sheer variety of comic styles incorporated and given a surreal edge in an unpredictable manner. Perhaps the ultimate meaning of Python lay in their willingness to trash any boundary of cultural convention that stood in their way – in the form of a grotesquely violent animation in the case of Gilliam's graphics.

Whatever the limitations of the Pythons' humour identified by dissidents, it has resonated down the generations, attracting legions of younger fans, and, despite its unmitigated Englishness, it has spread abroad. If you want to grasp the show's global impact, consider that Elvis Presley, no less, liked to quote favourite lines from Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

When I interviewed him about the troupe's 25th anniversary in 1994, actor Steve Coogan recited the entire "Cheese Shop" sketch word for word. "My mum would get me to replicate the previous night's show," said Coogan in 2009. "There were no video recorders then, so I became like a VCR. I would get angry if I heard other people doing it and getting it wrong."

Another generation on, Russell Brand has recalled being exposed to Python when young. "The virus of it grew in me as a child," he says. "In a way, it's quite sophisticated. But as a kid you can appreciate the silliness of it."

Despite intermittent reports of tensions, rifts and minor feuds over the years, all members of the team claim to spend their time giggling whenever they get together. They certainly seem to enjoy winding each other up. Iain Johnstone, who made a documentary about the Pythons and co-wrote the screenplay, with Cleese, of Cleese's movie Fierce Creatures, recalls an incident on the set of Life of Brian when Idle "arrived with a glorious American girlfriend, Tania [who became his wife], so he got a bit of baiting. Eric had turned vegetarian, so Terry Gilliam dressed his market stall [in the sketch] with rotting carcasses."

Idle acknowledges that today, with a short rehearsal period in an arena far larger than any they have ever played before, "we're going to have to hit the ground running", but he rejects the idea that their age will impede them. "I used to see the Crazy Gang [an anarchic British stage troupe] when they were old," he recalls, "and they were still terrific. This is that experience. People will be able to say, 'Before they died, I saw them all do it'. You don't stop being funny just because you're old."

So what is Idle's final comment on all the negative pre-publicity? "I like to rise beneath it," he says, laughing.

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in 'Newsweek'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments