Pelléas et Mélisande, Holland Park, London <br />The Pearl Fishers, Coliseum, London <br />Carmen, Holland Park, London

Thwarted love under canvas is both highly poetic and oddly provocative

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Evening sunshine is an unwanted visitor in Pelléas et Mélisande. Debussy's score needs darkness, its aromatic choirs of strings and woodwind blooming secretively. It's a powerful drug, this enigmatic work with its crippled, deceptive, inarticulate characters, its quiet pools of fresh, salt and stagnant water. Listen to the music and you're there, in the forest, looking up at Mélisande's moon-white face and cloudless eyes. But only when the shadows outside begin to match those on stage does Olivia Fuchs's elegiac, abstracted production for Opera Holland Park blossom. You can fake sunshine in a theatre, but you cannot fake nightfall in a tent.

Fuchs' Pelléas is both highly poetic and oddly provocative. The trees in Yannis Thavoris's Allemonde are strings of mirrored leaves, the cave a white cylinder lined with silver. Arkel's castle is a steeply raked corridor with a single silver chair for the half-blind king (Brian Bannantyne-Scott) and his weary, wary daughter (Anne Mason). Its reverse is the vertiginous cliff path, its base the claustrophobic cellar with its "smell of death". Below the castle is a white plinth, precariously balanced on a small black ball, then neatly fixed in place by the seven Félix Vallotton nymphs who shadow Mélisande's movements in dance and mime.

In terms of the energy required to negotiate its angles, the set is a symbolist hamster cage. Yet there is also clarity and calm: the silent sobbing of Anne-Sophie Duprels' Mélisande to the sobs of the violins, and the exquisitely detailed choreography of the lovers' hands under Colin Grenfell's close lighting in Act IV. Duprels' gleaming Mélisande is both an innocent and a liar, a blank canvas; Palle Knudsen's Pelléas a feeble, damaged child; Alan Opie's Golaud indelibly stained by shame, almost Bluebeard-like. The singing is wonderful, the conducting and playing disciplined, delicate, opulent. For Brad Cohen and the City of London Sinfonia this is a magnificent achievement: a symphonic score played as chamber music.

Bizet died at the age of 36, leaving one operatic masterpiece. The subjects he considered and abandoned in his twenties – Le tonnelier de Nuremberg, Hamlet, Clarissa, Don Quixote, the Sanskrit epic Ramayana – indicate a taste for serious literature. But only his one-act harem drama Djamileh approaches the concentrate of colour and characterisation he would achieve in Carmen. Written 10 years earlier and set in Ceylon (Mexico had been mooted as an alternative location), The Pearl Fishers is a pallid failure, devoid of local colour. As pious as Carmen is fatalistic, its subject is self-abnegation, its heroine a virgin priestess.

Penny Woolcock's production for English National Opera opens with an image of luxurious beauty, as three aerialists "dive" into a sea of turquoise gauze. Bizet's prelude thus dispensed with, she begins a critique of contemporary orientalism. Two sun-burned back-packers wander through a Salgado-style shanty town, recording the quainter details of Third World poverty on their digital cameras. In a portent of the conflagration to come, one local strings electric cables over the water, while another cooks bread on a portable gas stove. Yes, it's a fire risk. That's the point.

Chewing the scenery must be bad for the waistline. Woolcock's wildly emoting, pseudo-Singalese chorus are notably plumper than her (non-singing) tourists, the Brahmins positively chunky. The Pearl Fishers is in any case a fragile vehicle for First World guilt, for the exotic details of Dick Bird's scrupulously researched set are not reflected in Bizet's score. Were Zurga (Kelsey Quinn) and Nadir (Alfie Boe) trawling the North Atlantic for cod, it would have no impact on their heroic hymn to friendship, "Au fond du temple saint".

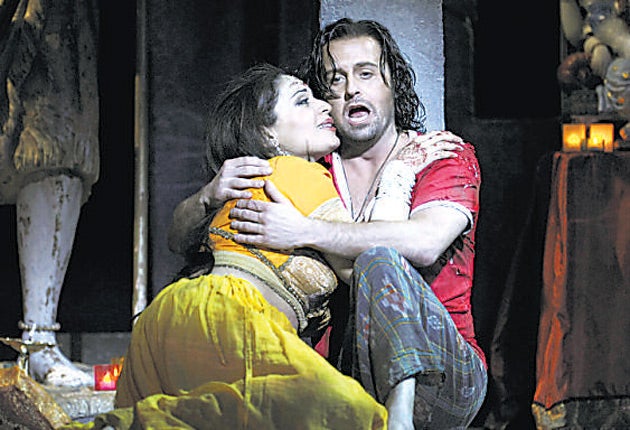

Gounod is the musical model, though Martin Fitzpatrick's Crimplene-and-curlers English translation takes the choruses within spitting distance of Stainer and Sullivan. With little characterisation in the score, Woolcock signals Nadir's impetuosity with a football shirt, and Leïla's (Hanan Alattar) purity with a complicated series of veils for Nadir to unwrap. Pretty but brittle of tone, Alattar sounds strained in this submissive role, while Boe is forced to maintain a bright forte over Rory Macdonald's uptight, stop-start conducting. Quinn's handsome baritone carries easily and suavely in the Coliseum but it is clear from The Pearl Fishers that Bizet's talent was for vice, not virtue.

Back at Holland Park, Jonathan Munby's production of Carmen opens with an air of barely suppressed sexual violence. Respectable women move swiftly past the army garrison, travelling in pairs, pulling their shawls around them, hoping not to attract the leering, the groping and the bullying. Those less lucky must run away or tough it out like Tara Venditti's Carmen. So much for high camp and castanets.

Handsome rather than beautiful, with wide cheekbones, a strong jaw and a flinty, smoky tone, Venditti is an interesting Carmen. The moment when she dips her finger into a glass of wine and draws it across her victim's lips in Lillas Pastia's bar is more effective for the watchful stillness that precedes it. It's a confident performance in a perceptive, economical staging, where the heroine's every move is studied by one of the street urchins (a precocious child unimpressed by the lot of women in 19th century Seville).

With Julia Sporsen's fearless, ardent Michaela, Munby's Carmen is something of a feminist piece, with an inevitable diminution of Sean Ruane's weak, baffled Don José and David Stephenson's understated Escamillo. Emma Wee's simple designs – two wooden panels and a shower of crimson petals – and some spirited work from the orchestra make for a pacy show, though conductor Matthew Willis needs to listen more closely in the ensembles.

'Pelléas et Mélisande' (0845 230 9769) to 16 Jun; 'The Pearl Fishers' (0871 911 0200) to 8 Jul; 'Carmen' (0845 230 9769) to 19 Jun

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments