Classical review: Written on the Skin - Gourmet braised heart, sweet'n'sour

A brilliant collaboration cooks a mediaeval love story into a crisp modern fable, with delectable orchestration on the side

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Adapted from the legend of Guillem de Cabestaing, the troubadour whose heart was fed to his lover by her husband, Written on Skin has arrived at the Royal Opera House garlanded with praise from its Aix-en-Provence premiere. George Benjamin's second opera with Martin Crimp is, in Crimp's words, "a hot story in a cool frame": a 90-minute sequence of gilded miniatures in which the contemporary is erased and the dead snap back to life, monitored by a septet of enigmatic angels.

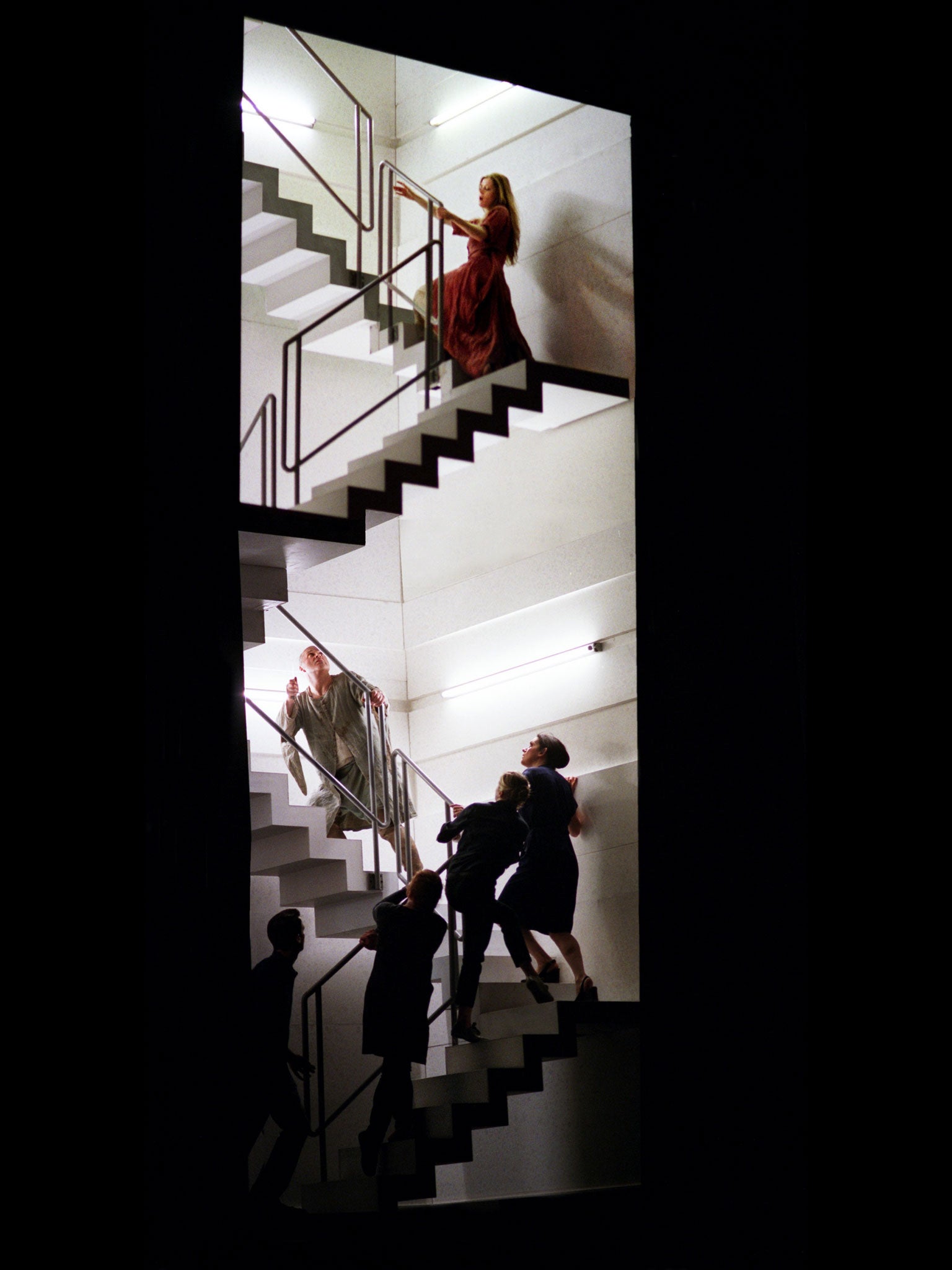

In Katie Mitchell's production, that cool frame is further refined. Vicki Mortimer's split-level set contrasts the rough floors and dark forest of mediaeval France with a modern laboratory where angel-archivists preserve the fragile artefacts of an 800-year-old story. Mortals and angels move through past and present, blinking in surprise at the fluorescent light, slowing their movements to the pulse of Benjamin's music and the crisp interplay of vowel and consonant in Crimp's impeccable vocabulary of rage and desire.

Agnès (Barbara Hannigan) is childless and illiterate, married at 14 to The Protector (Christopher Purves), a man "addicted to purity and violence". Does she seduce the Boy/Angel 1 (Bejun Mehta), who is commissioned to immortalise The Protector's life in an illuminated book? Or does he seduce her? Her fall is preordained, and her sister (Victoria Simmonds) and brother-in-law (Allan Clayton) are also angels in disguise.

The orchestra, cast and stage are bigger, but the sharp focus of Crimp and Benjamin's 2006 collaboration, Into the Little Hill, remains. Crimp's text is spare and poetic, precise and effective in its language of erotic obsession, with insistent variations ("wet like a woman's mouth", "wet as the white of an egg") and a fixation with the "secret bed". But Crimp's Boy is curiously detached: an agent of liberation and damnation, with a voice of lethal androgynous sweetness.

Benjamin cites his favourite operas as Pelléas et Mélisande and Wozzeck, but only occasionally does he relax into the blue-green shadows of Debussy or the convulsive violence of Berg. Faint echoes of Britten's Canticles in the word-setting evaporate on close listening. Benjamin is sparing in his use of melisma, self-effacing to the extent that Crimp's text leaves more impression than the vocal lines. It is the orchestral writing that lingers in the ear, the damp, furtive woodwind, the muted horns, the whine of a bow drawn across the rim of a bell, the moondrunk glass harmonica, the delicate tracery of viola da gamba, icy and ephemeral.

With each use of indirect speech, Benjamin and Crimp compel the listener to step back. Even the horrible climax, where Agnès exults in the disgust of devouring her lover's heart, is controlled. Her suicidal ascent is enacted in slow motion over a vaporous sheen of strings as we close the ancient book with latex-gloved hands, never to see her leap.

A faultless orchestral performance and singing of incredible energy and beauty from Hannigan and Purves make Written on Skin remarkable. Whether a work so absolute in its perfectionism could withstand a staging less attuned to that aesthetic than Mitchell's remains to be seen.

Such perfectionism wouldn't go amiss in The Siege of Calais (Hackney Empire, London ***), wild card in English Touring Opera's spring season. Donizetti's unfairly neglected opera suffers from scruffy blocking and a radical amputation of its third act in James Conway's production, updated to the 20th century and set against a broken sewer-pipe.

Powerful, stylish and supple performances from Helen Sherman (Aurelio), Paula Sides (Eleonora) and Eddie Wade (Eustachio) anchor a work of high moral purpose in which six men decide to sacrifice themselves for the sake of their community. Jeremy Silver conducted the orchestra with panache but I worried for the baby son (a swaddled doll), casually passed from citizen to citizen. I've seen baguettes handled with more care. Especially in Calais.

Christopher Rousset's concert performance of Lully's Phaëton (Barbican, London ****) was blessed by an orchestral performance of unstinting suavity. While British Baroque specialists still tremble at every tricky musical ornament, Les Talens Lyriques play with such fluency that decorative details never interrupt the curve of a phrase, the strings mellowed by flutes or brightened with oboes. This bouyancy extends to Rousset's choir, its haute-contres trilling prettily at the cadences. In a mixed-ability cast, Andrew Foster-Williams's burnished Epaphus, Sophie Bevan's plangent Libye and Ingrid Perruche's fretful Clymène stood out for the depth of their characterisations. Though pilloried for his attitude to his rivals, Lully was a keen observer of human (and godly) frailty: vanity, ambition and self-deception.

'Written on Skin' (020-7304 4000) Mon and Fri (returns only); 'The Siege of Calais', Exeter Northcott (01392 493493) Fri, then touring

Critic's Choice

Ian Page and the Classical Opera Company present the UK premiere of Telemann's 1726 opera Orpheus as part of the London Handel Festival at St George's Church, Hanover Square (Monday). Stefan Janksi directs the Royal Northern College of Music's bright young things in Paradise Moscow, Shostakovich's satire on corruption in a housing development in the Krushchev era. It's at the RNCM Theatre, Manchester, (from Thu).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments