Otello: Why is a white tenor leading the Royal Opera House's new production?

The end of blackface make-up promised a new dawn for singers of colour, writes Alison Kinney

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Royal Opera House (ROH) has announced its 2016-17 season, including its first new production of Giuseppe Verdi's opera Otello in 30 years, starring the tenor Jonas Kaufmann in the title role.

Based on Shakespeare's play, Otello is the story of how a Moorish outsider, general, and husband, succumbs to the hateful bigotry of his community. Because Otello is also one of few 19th-century operas whose hero is a man of colour, it's perhaps inevitable that it should also galvanise debates about race and racism in the opera world. Verdi dubbed his work-in-progress the "chocolate project". He wrote: "You can hardly have Otello dressed as a Turk, but why not have him dressed as an Ethiopian," establishing the operatic tradition of Otello looking "black", being regarded by directors and audiences as black, and being sung, to this day, almost exclusively by white tenors in dark theatrical make-up.

When the English National Opera, in 2014, and the Metropolitan Opera, in 2015, renounced such make-up, opera fans responded with bravos and boos. Now, the ROH's director of opera, Kasper Holten, says: "Otello will not wear black make-up in this production. The production will focus on Otello struggling with questions of identity, having been uprooted and living in a culture that is ultimately foreign to him, rather than the question of race as such."

Kaufmann's debut as Otello is widely anticipated. Yet, while relishing the possibilities of this production, it's neither a slight nor an inconsistency to ask how the spectacle of white tenors singing a role traditionally interpreted as that of a persecuted black man might contribute to the conversation about diversity in the profession. Many singers of colour regard the demise of racialised theatrical make-up as a necessary, overdue, but minimal intervention, distracting from issues of inequality in the training, funding, and hiring of non-white singers.

Holten adds: "We feel all great singers should have the possibility of taking on the great iconic parts in the repertory, regardless of the race or background of the singer and of the character portrayed. We do feel the opera world needs to work harder on diversity and we will be working hard at ROH in coming years to support the development of more diverse talent, all given equal opportunities to excel in the operatic repertory."

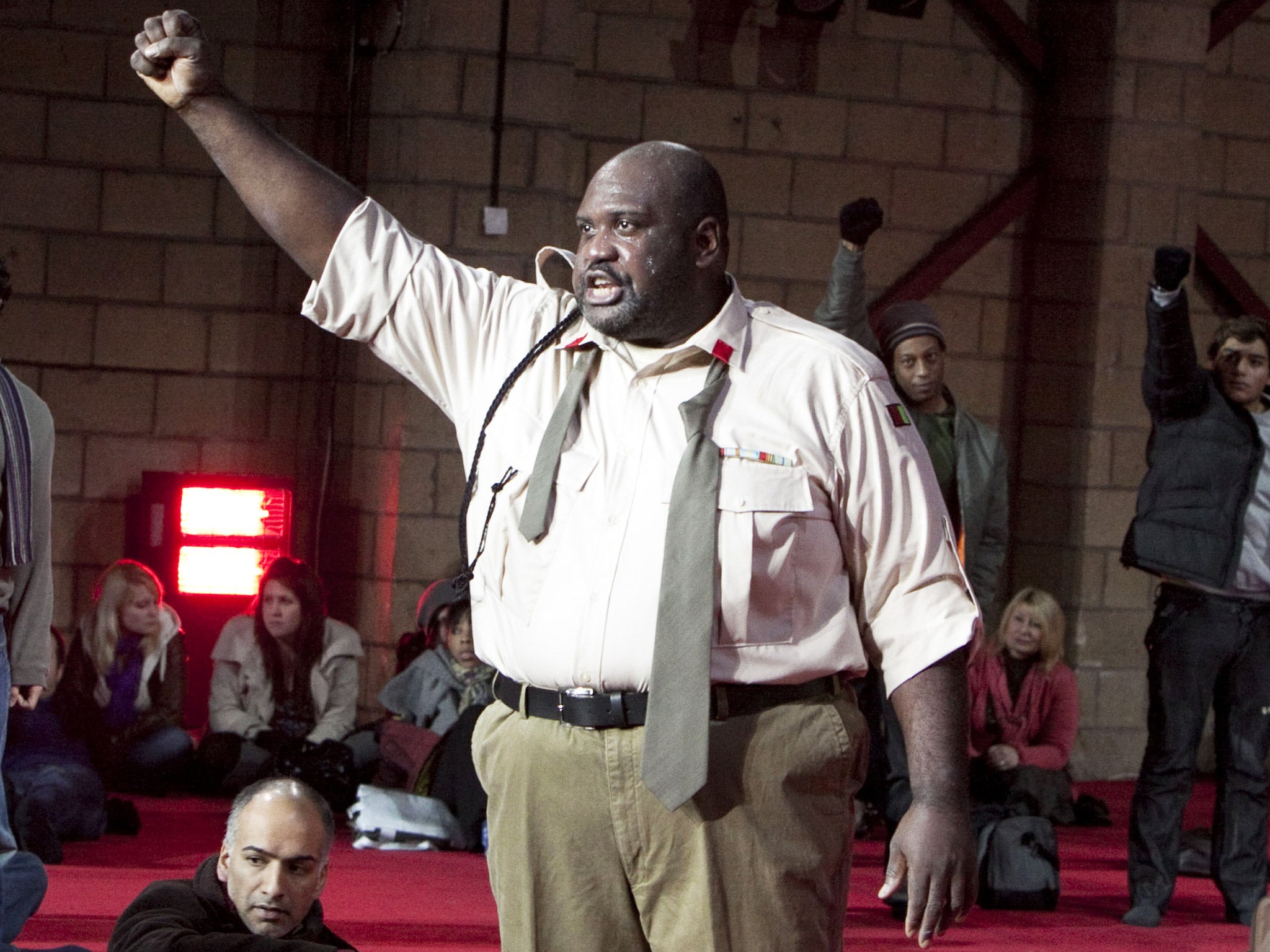

When Howard Haskin auditioned for Otello in 1994, the Opéra de Nice turned him down. "Because I was black," says Haskin. However, after their first choice for the lead role cancelled, Nice begged Haskin to step in. Having become the first black dramatic tenor to sing Verdi's Otello on the operatic stage, Haskin remains one of only a handful ever to do so. But the black tenors who sing Otello have quietly carried on with their rehearsals. They're eager to talk, not about criticisms or resentment, but about the poignancy, beauty, and relevance of the role. "For me as a youngster, Otello was a dream. I always thought that once I could sing it, I'd be so happy. And that's what came to pass," says Ronald Samm, the first black tenor to sing the role in the UK (with the Birmingham Opera Company in 2009). "I've never found another role even close to what it gives me back, acting-wise."

"Verdi's music is so enchanting that one can't help but be emotionally swept away," says Texan-born Ray M Wade, Jr. After his seventh turn as Otello in Germany, he said: "I have made Otello mine." Michael Austin, the first black tenor to sing Otello at a US house (Cleveland in 2004, and then Knoxville, 2012) says that, two decades ago, he "wouldn't be singing Otello in Knoxville, because the opportunity wasn't there." In the 1980s, Austin sang Alfredo in a production of La Traviata that reopened in Alabama without him. "They said: 'We won't have an African-American tenor kissing a white soprano in Mobile,'" he says.

The fragmentary history of black opera-singers in the role has been salvaged by the African-American press, music scholars and singers: Lawrence Watson (a Buffalo Symphony Orchestra concert in 1956), Charles Holland (De Nederlandse Opera, 1957), and Nathan Boyd (Spoleto, 1965) emerged as the first Otellos. Yet Holland and Boyd were lyric tenors, induced to sing a dramatic role that was unsuitable and potentially ruinous to their voices, because they, supposedly, looked the part. Black lyric tenors from the legendary George Shirley to contemporary star Noah Stewart have had to resist similar pressures. It's the flip-side of racial discrimination: some opera houses insist their all-white casting results from hiring only the best, so as to uphold musical standards, yet their quick fixes for diversity are both racially and musically oblivious.

Singers of colour who discuss racism often have to dodge accusations of sour grapes. "I don't wish to come off as jilted or slighted in any way, but, as a black tenor, it has not been easy," says Wade. "This is the medium I love, and in which I excel, and I can't allow other people's racial bias stop me."

Otello can serve as a metaphor for black tenors' experiences with prejudice, but that's precisely why these singers don't want hostility. Haskin says: "I am not asking for roles like Otello to be exclusive to black singers. I certainly do not begrudge… Mr Kaufmann singing Otello." Rather, he longs for the day when "major companies will be able to hire black tenors for the role without reservation".

For these singers, opera is a passionate, vital, and profoundly relevant art form. They sing Otello for a changing world – and they, too, change with the role. Samm says: "The first time I did Otello in Birmingham, I was a bit wide-eyed. You say, 'aargh!', and you go for it. [But] you grow into each performance; you get stamina; you want to try it differently." His voice fills with delight. "Each time I sing it, I get better, and, next time, maybe they'll call me."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments