Good vibrations in a brave new classical world

Some of Britain's biggest rock stars are joining forces with a famous orchestra – with thrilling results, says Nicola Christie

The BBC Concert Orchestra has gone a little crazy. The stage is a tip – there are leads strewn all over it – there are weird women waving their hands in the air, witch-like, and the audience, never mind the players, have never heard half these sounds before, or at least seen how these sounds are generated.

The BBC Concert Orchestra has gone Electronica. Three concerts, the first of which took place at the South Bank's Queen Elizabeth Hall last week, to celebrate a world of instruments that have, for the most part, been shunned by the classical music world. They're now sitting proudly at the front of the stage, the stars of the show.

"You know we didn't even know where to put them!" says Goldfrapp's Will Gregory, the one behind Alison Goldfrapp's whizzy, giddy sound. He's working on an electronica opera – it will premiere at the Ether Festival next March – and the QEH concert offered him the opportunity to try out a selection of the material.

"I've a pile of Moogs on the stage – these are the earliest synthesisers, designed by Robert Moog in the 1960s – and they have to be amplified. Which means they have leads, they need to be plugged in, they have huge speakers to attach to. Where do all those objects even fit on an orchestra stage?"

Gregory has a point. His Moogs are an absolute invasion, the antithesis of the lovingly carved wooden and brass instruments that have evolved over thousands of years as the signature instruments of the orchestra. They need electricity, not wind, to make their sound and their music is... Well is it music? Atmospheres, sound worlds, effects, yes; but music in the "real" sense of the word?

"This is what I'm interested in," replies Gregory. "Why have these instruments rarely made it into the orchestra? What happens when the two worlds come together?"

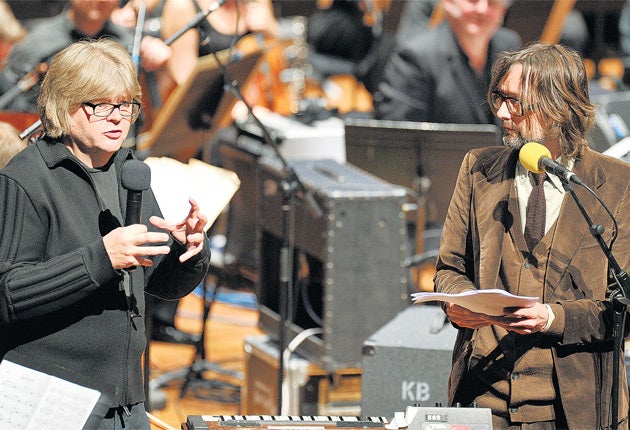

The answer, with consummate mastering of both fields and, ultimately, exquisite musicianship, is something quite special. The large, sweeping orchestral sound gets transported when Gregory's Moogs kick in; when Radiohead's Jonny Greenwood – the composer-in-residence of the BBC Concert Orchestra, whose first orchestral writing, Smear, featured in the QEH concert – marries his orchestra with two Ondes Martenots (keyboard/ string/electronic-type instruments), it all starts to sound very strange.

"Ever since Alison and I discovered what happens when you put this synth sound, totally raw and unrefined, over this beautifully perfected high violin section, it just spun us somewhere really interesting," Gregory explains. "And I am now constantly hankering for subverting what the orchestra stands for with these inhuman, robotic-sounding machines. When you put the two together they just rub in an interesting way. Obviously there are some very interesting things that they will do that the other instruments in an orchestra can't – they will go much lower, below 50 Herz, and much higher; they have much greater extremes of ranges. There are loads of sounds that a synth makes, and colours, that you won't get from an orchestra. So in one way, you could regard it as trying to expand the possibilities of what an orchestra can do. On another level you could regard it as trying to expand the possibilities of what a synthesiser can do. Sometimes I use the orchestra to back the synths, and sometimes it's the opposite."

In the case of Greenwood's Smear, his inclusion of the swooping, mind-bending Ondes Martenots – so rarely used that they are impossible to track down – is just the final sludge on what his orchestra of strings are already doing. They smear themselves between two tiny points on a musical scale so that there is this growing mush of fledgling, uncertain sound. "I've written Smear in a Messiaen mode [the 20th-century French composer Olivier Messiaen, famous for creating his own set of modes and also for his use of the Ondes Martenot, developed in France in 1928). I wanted to have quarter tones as well, and so there's this sort of smear of all of the tones at 2 points in the scale."

I ask Greenwood whether a Radiohead fan would be able to hear that it is him in Smear, and the subsequent orchestral writing that Greenwood has done for film (the upcoming Norwegian Wood plus Ivor Novello award-winning There Will Be Blood) and orchestra. "I think so. I like the same things whether I am writing for 40 players or for the five of us in the band; I like it when music sounds slightly wrong, when you can hear the hesitations and mistakes. I like working that out – the discomfort of it. As a title, Smear, I was also trying to capture the feeling of something starting to slide. It's a frightening word, isn't it?"

Watching Greenwood at work with the orchestra, you get the sense that he still, six years after being appointed the resident composer of the BBCO, needs to pinch himself. "I can't get over it. The sound of this number of players in a room, all together. That moment just before the orchestra starts, and then the first chord; this sound has come out of nowhere – it's like nothing you have ever heard, and it's coming from everywhere, not just two little speakers. That's really addictive. And it's also the event of it. When I play with Radiohead, we're chipping away at something from the very beginning; you can always hear what it's going to sound like. With an orchestra, you have a process where, for months and months, something just exists on paper. When I was recording the film score to Norwegian Wood at Abbey Road, six months ago, I would get there early and see them putting out all of the music stands, the empty stands, knowing that in four hours time it was going to be finished; all the scores would be on the floor and it would be over."

There were some eyebrows raised in 2004 when Radio 3 controller Roger Wright invited Greenwood to be the composer in residence of the BBC Concert Orchestra; but he was right. It is the non-classical musical stars who need to put themselves into the orchestra pit, solve the problem of how to do – with a giant body of players – what they do in headlining gigs at Glastonbury and in recordings that sell, globally, in their millions. How better to further the repertoire of an orchestra? And how better to genuinely seed a possible new contemporary classical movement that could actually resonate with a young audience? I'm not talking about the credence of these guys, their cult status, but about their musical genius that actually has the chance, if properly guided, to move the classical language on in a way that contemporary classical music often fails to do.

The performance of Gregory's opera, Journeys into the Sky, about the efforts of Swiss balloonist Auguste Piccard to reach the stratosphere, could be a landmark piece in that new movement when it premieres at the Queen Elizabeth Hall next March. Librettist Hattie Naylor has almost finished her first draft and, on the strength of the selection of music performed on 6 October, Gregory is genuinely going to astound with his vision of what can happen when part of an orchestra is plugged in. "There is an alienness to these instruments, isn't there? It's like a bunch of electronic circuits trying to buzz along in a musical way; ultimately I think they fail to be, to our ears, truly human, but it is the degree to which they fail which is interesting – and also there's something slightly moving about the fact that they can't do it. They're like poor little aliens that want to be alive and can't be. I think there are many more sounds to be found, and ways of using them, which we haven't explored."

The 6 October Electronica concert will be broadcast on Radio 3's 'Performance on 3' on Friday 19 November at 7pm. The next 2 Electronica concerts will take place on 31 March and 9 June 2011 .

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments