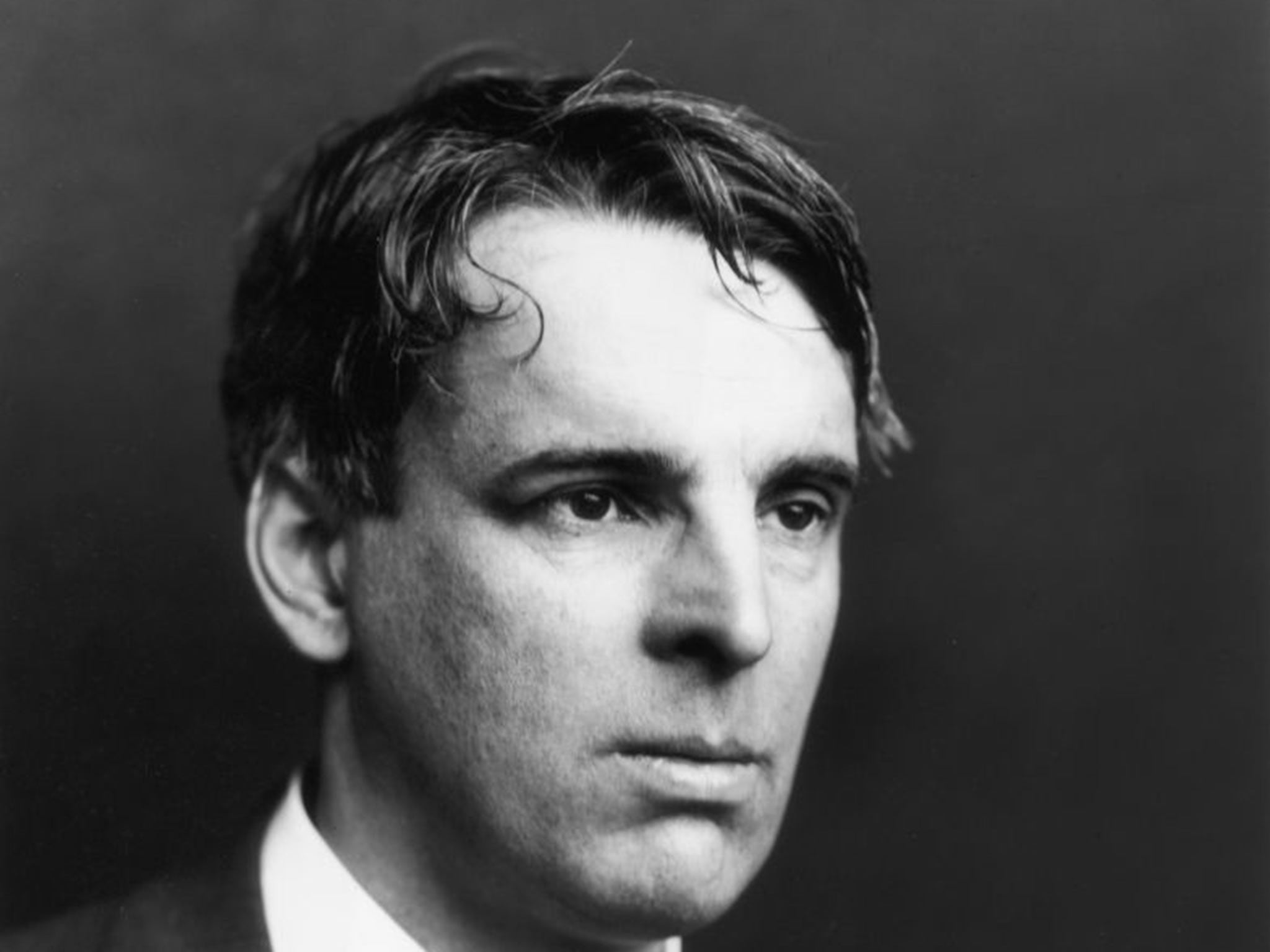

WB Yeat's beloved Maud Gonne knew that poets should never marry

'It set the pattern for the rest of their lives: her determination that theirs should be a spiritual union, a mystical marriage, an astral connection, an amitié amoureuse'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tomorrow is Valentine’s Day, and our thoughts turn naturally to romance among the titans of art. Say what you like about Dante and Beatrice, Abelard and Heloise, Keats and Fanny Brawne – for me the best literary love story remains that of Willie Yeats and his beloved Maud Gonne.

It isn’t just the chronicle of a poetic chap who fancied a pretty girl and wrote some romantic verses to her; their tormented relationship was conducted against the backdrop of the Irish Rising a century ago, and Yeats’s love for Maud became inextricably bound up in his admiration of radicalised nationalism. It’s also a fascinating record of delusion and secrecy, and of a lover being led a merry dance for many years.

They met 127 years ago on 30 January 1889 in London, when Willie was living with his sisters near Chiswick. Maud had known their father when he was a painter in Dublin, and came a-calling. “A hansom drove up to our door at Bedford Park with Miss Maud Gonne,” Yeats wrote, “and the troubling of my life began.” She was an amazing sight: six feet tall, bronze-haired with huge melancholy eyes and beautiful skin, an English ex-debutante of 22, the daughter of an army officer, with a passion for Irish nationalism and a love for romantic poetry, “a fin de siècle beauty in Valkyrie mode”, wrote Yeats’s biographer, Roy Foster, “and both her appearance and character represented tragic passion”.

How could Yeats not fall for her? His memory of her was understandably confused: he remembered her standing luminous as “apple blossom through which the light falls... by a great heap of such blossoms by the window” – even though, of course, apple blossom is nowhere to be seen in January. His sisters Lily and Lolly “hated her regal sort of smile”, disapproved of her slippers, but were impressed by the well-heeled insouciance with which she left the cab waiting at the front door.

Yeats asked her to dinner the next evening; they saw each other every day the following week. He was 24, bearded, dark, intense, socially maladroit but, with the publication of The Wanderings of Oisin behind him, growing in confidence and making his name around London, giving talks to literary salons and wowing the ladies with his passionate readings. How could she not be impressed?

But Maud was harbouring a secret. She was having an affair with Lucien Millevoye, a much older and married right-wing French journalist and politician, whom she’d met two years earlier at a spa. Three months after meeting Yeats, she was pregnant with Millevoye’s child; it was born in late 1889 but died in 1891. Yeats knew nothing about these matters until she confessed all, years later. Maud managed to keep them quiet by retreating to her house in Paris and keeping her Irish suitor at arm’s length.

But their worlds kept colliding. Yeats wrote articles about her inspirational speaking tours on behalf of evicted Irish peasants, talks that reduced sophisticated Parisian aristocrats to tears, not realising that her radicalism had been tutored by Millevoye’s political sympathies. When Willie introduced her to occult societies such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, she embraced them in the hope that they might reincarnate her dead baby. Yeats was oblivious to that too.

When they met in Ireland after the child’s death in 1891, Yeats discovered her exhausted and vulnerable, and fell in love with this different side to her personality. Possibly seeing where things were heading, Maud told him about a dream she’d had, in which they’d been brother and sister in a past life, sold into slavery in Arabia. Yeats liked the idea of their spiritual association but got the message that she wanted only a platonic relationship.

Straightaway he went to her and proposed. She refused, said she’d never marry and explained that she had a morbid dread of sex, but hoped they’d always be friends. Together they visited Howth Head in Dublin Bay, talked about their feelings, and afterwards he sent her “The White Birds,” his first of many poems about her, describing, not entirely convincingly, his longing for a land beyond passion, desire and smut.

It set the pattern for the rest of their lives: her determination that theirs should be a spiritual union, a mystical marriage, an astral connection, an amitié amoureuse, while she devoted herself to the Irish struggle for independence and co-founded the Irish League; while Yeats wrote beautiful poems about his sexual torment and her enraging commitment to action of the wrong kind. He proposed to her three more times, unsuccessfully. But they remained close right up to his death in 1939.

And that would be the whole frustrating love story, except for one thing. Yeats scholars gradually wondered exactly what took place in the summer of 1908, when Maud was emerging from a long divorce case against her husband, John MacBride. She was 41; Yeats was 43. Their correspondence ceased being entirely astral. They were reunited in Paris, Dublin and London. She wrote that she’d dreamed of him becoming a great serpent – and during a month-long stay in Paris, it seems they became lovers. A later poem recalls her lying in his arms and crying in his ear, “Strike me if I shriek!”

Judging by her letters, she soon went back to insisting on spiritual union. But we readers can be pleased that the poet and his muse gave consummation at least one shot. Perhaps we should regard their relationship as merely the occasion for immortal poetry, as Maud did. When Yeats told her he wasn’t happy without her, she replied: “Oh yes, you are, because you make beautiful poetry out of what you call your unhappiness, and are happy in that. Marriage would be such a dull affair. Poets should never marry. The world should thank me for not marrying you.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments