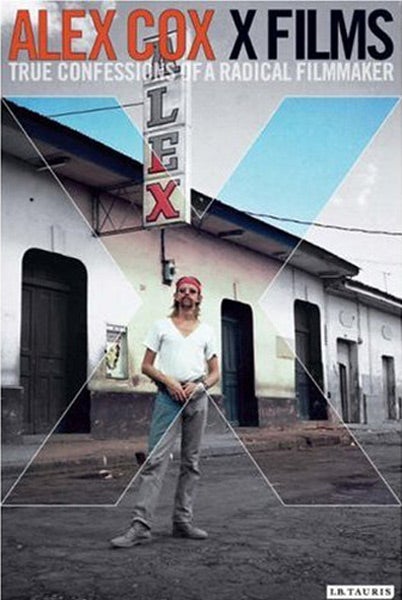

X Films, by Alex Cox

An intriguing picture of life on the movie scene, by a maverick film-maker

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

A whole generation of film buffs grew up with Alex Cox. From 1988 to 1994, he presented Moviedrome for the BBC, his soft voice guiding you into the nether regions of cult film. After making Repo Man and Sid and Nancy, he wasn't just a hipster but a film-maker with credibility, and a moral compass that appealed to fellow artists including Joe Strummer, with whom he worked over many subsequent films. He always looked cool, in an etiolated, desert-bleached, Nick Cave kind of way.

His new book doesn't offer much in the way of anecdotes, but is a very revealing look at the day-to-day difficulty of being an independent film-maker. Every student at film school should be obliged to read it. It shows how bad things can get: throughout his 30-year career, Cox provides ample demonstrations of how crass industry lawyers are, how bonds and copyright issues destroy the artistic impulse (intriguingly, he argues for a massive deregulation of copyright), and how big companies refuse to distribute films after having bought them. But it also reveals the sense of fun, of purpose, of liberation, that being a low-budget film-maker can bring.

"Today an independent filmmaker is a revolutionary fighter," he tells us, while suspecting "the feature film is dead". He never quite explains what he means. Increasingly, his politics seem all, culminating in his 1987 film Walker, made in Nicaragua with the help of the Sandinistas. To my knowledge, this film has only been shown in the UK a handful of times, but Cox devotes a great deal of time to talking about it. In many ways it forms the apogee of his link between leftist ideology and film-making.

On the whole, Cox steers clear of personal comment in favour of the big picture, but sometimes his remarks are perversely ad hominem. Witness his attack on William Burroughs as "a snob, a bad painter, a wife-killer and a trust-fund junkie".

There's also a yawning gap, a cavernous absence. In 1997, Cox was hired to write a script for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas; it was he who first brought Johnny Depp into the project. But by all accounts Hunter S Thompson couldn't stand the film-maker, defiantly watching football all the time, messing around with blow-up dolls, and triumphantly serving meat feasts for the piously vegetarian Cox. Alas, of his encounters with the gonzo god, Cox breathes not a word, and the project is not even mentioned.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments