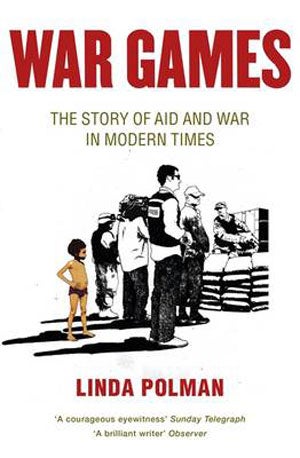

War Games: The Story of Aid and War in Modern Times, By Linda Polman

How our charity can have unintended consequences

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Aid is simple: donate some money and lives will be saved. We have been encouraged to urge the West to "Drop the Debt" and wear a white wristband to "Make Poverty History", while one aid agency is currently pulling at our heartstrings with the slogan "We Save the Children. Will You?" But as Linda Polman's War Games reveals, the delivery of aid can often have unintended consequences. Relying on decades of experience as a journalist covering wars and humanitarian crises from Rwanda to Afghanistan, Polman eviscerates an industry that is often held up as a paragon of virtue.

Aid, she argues, can prolong conflicts and endanger the lives of the very people it is supposed to save. Wars attract aid, and as a rebel in the Sierra Leone countryside points out, the more violence there is, the more aid will arrive. "WAR means 'Waste All Resources'," he says. "Destroy everything. Then you people will come and fix it."

The aid industry – and it is an industry – deserves a large part of the blame for this. For decades we have been sold simple messages as if there are simple solutions. The complexities of aid have been deliberately ignored. Earlier this year, the BBC alleged that some of the money raised from Bob Geldof's Band Aid had been siphoned off by Ethiopian rebels and spent on arms. The allegation was vigorously denied, but to those who work in aid, this was not surprising. To deliver humanitarian assistance in warzones often requires making arrangements and cutting deals with armed groups. If a Congolese rebel group tells an aid agency they can deliver food in their areas only if they hand over 10 per cent to them, what should that agency do? Accept the compromise or pack up and go home? Neither option is straightforward.

This is a short book, 164 pages plus notes, and it would have benefited from a greater analysis of how aid agencies and NGOs (non-governmental organisations) have developed over the past decade. Many NGOs are no longer merely humanitarian actors. They are also advocates and campaigners. But working to save lives in a warzone while simultaneously trying to raise awareness of the causes of the conflict can lead to problems. Can the NGO working in Darfur criticise the Sudanese government which allows it to operate? Will NGO workers in Afghanistan be in danger if head office puts out a press release criticising the Taliban?

All of which has made the job of the humanitarian worker increasingly hazardous. According to Polman it has now become the fifth most-dangerous profession in the world, after lumberjack, pilot, fisherman and steelworker.

Polman has written a modern-day version of Mother Courage; a searing account of how aid can fuel the conflicts it tries to stop. But it is soured somewhat by what seems like a distaste for aid workers. With one exception, the aid workers she meets are portrayed as heartless men and women who tell disparaging jokes about the people they claim to help, while spending their evenings drinking bottles of expensive French wine and their days off playing rounds of golf.

It is here I must make a confession: I like aid workers. Some of my best friends are aid workers. My partner is an aid worker. Maybe I have been exposed to them for too long, but the vast majority of aid workers I know are good people trying to do the right thing in often difficult circumstances.

They don't always get it right but many of them are constantly questioning their methods. The question which Polman rightly insists must be asked – can aid prolong conflicts? – is already being discussed by aid workers in dusty refugee camps in Darfur and, yes, around dinner tables in plush Nairobi restaurants. Polman's timely book should help to spread the debate further.

Steve Bloomfield is the author of 'Africa United: How Football Explains Africa' (Canongate, £12.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments