Vncent Van Gogh. Ever Yours: The Essential Letters, edited by Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten and Nienke Bakker, book review

Boyd Tonkin discovers that the remarkable artist was also an avid reader and an accomplished writer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Although he thought "all of Dickens beautiful", the young Vincent van Gogh took special care to re-read A Christmas Carol once a year. "In my view there's no other writer who's as much a painter and draughtsman as Dickens," he told his artist friend Anthon van Rappard from The Hague in 1883.

Three years earlier, the footloose Dutch pastor's son – first a trainee art dealer, then a preacher and teacher in London and Brabant – had plunged into a belated vocation. Surprisingly, he took up a calling for the image rather than the word. Over the decade up to his self-inflicted death at Auvers in July 1890, Vincent drove himself through an astonishing spiral of growth. Even more remarkably, when he set out on his mission as an artist, this avid reader, correspondent and student of literature was already an accomplished writer.

"What ifs?" strew Vincent's brief, incandescent path through life. Among his early heroes were the English artist-illustrators whose drawings helped tell stories in papers such as the Illustrated London News. In 1883, he still pondered the prospects for "work and a salary" from such a job in London. In an alternative steampunk universe, Vincent – disciple of Shakespeare and Zola, and Dickens's self-anointed heir – might have pioneered the graphic novel as high art.

Paris and Impressionism beckoned, followed by bliss and breakdown in the "Studio of the South" with Paul Gauguin in Arles. But Vincent never ceased to write – above all to his art-dealer brother and financial prop, Theo van Gogh. His 819 letters (658 to Theo) make up not only a creative autobiography without parallel in visual art but what the editors of this selection call "a highlight of world literature".

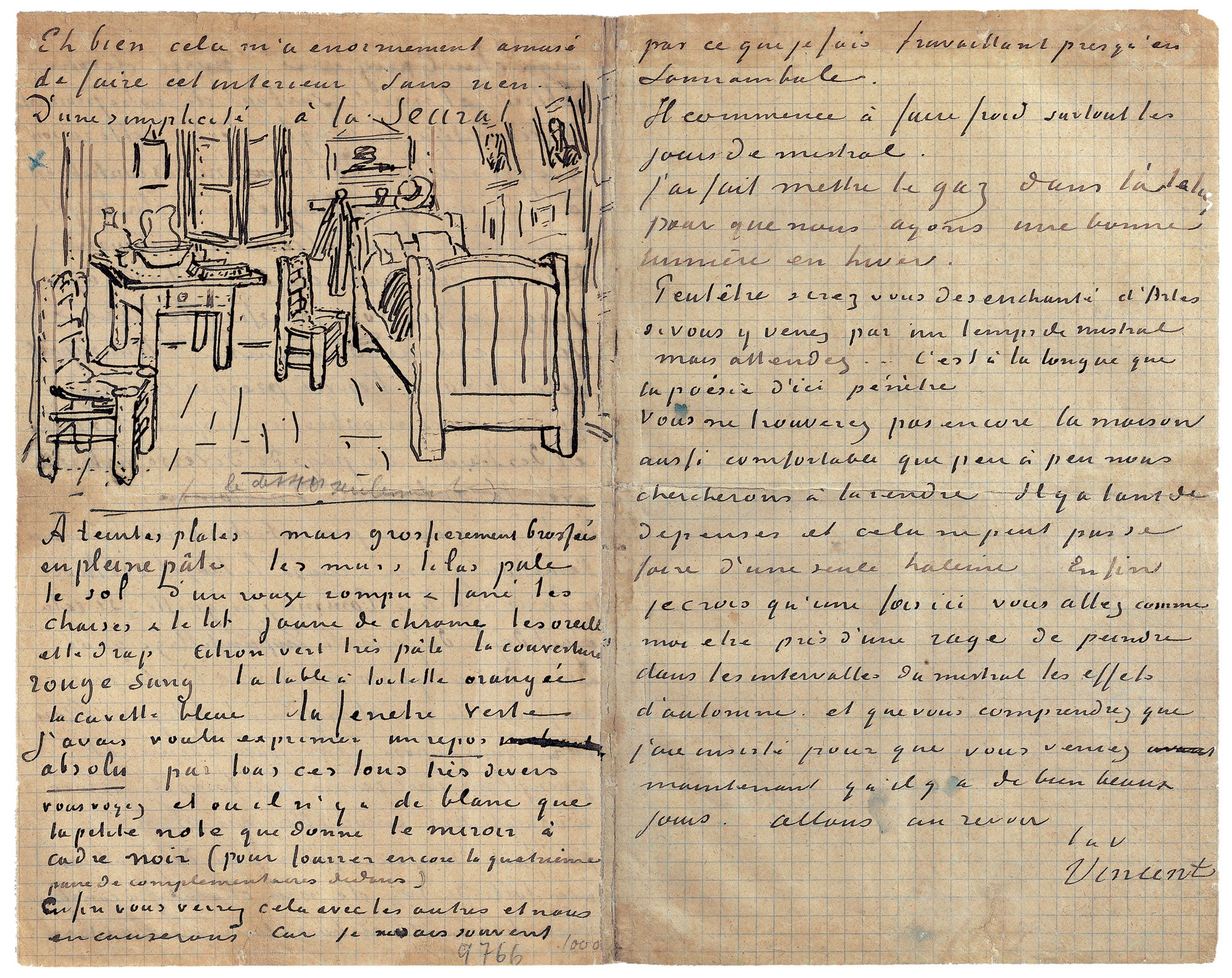

In 2009, Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten and Nienke Bakker completed 15 years of work on a definitive edition of the correspondence. They curated a wonderful exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, while the lavishly illustrated six-volume boxed set went on sale for £395. However, thanks to generous Dutch state support, the online version –vangoghletters.org – remains a magnificent free resource. Still, lovers not only of great art but great autobiography should devour this ample sample. A bargain at 770 pages, enriched by scores of the drawings (or "croquis") with which Vincent explained his works-in-progress, the volume knits 265 letters into a coherent, impassioned and eloquent pilgrim's progress.

When he lived in Isleworth Vincent, the fledgling evangelist, wrote in a sermon that "we are pilgrims on the earth and strangers". His long, often tortured quest for an art that would embody all his yearning and insight was also a thwarted search for home. Apart from the rock-like Theo, people often fell short of his shifting ideals – whether pious, puritanical "Pa and Ma", the prostitute Sien whom he sought to love and "save", or erratic, disruptive Gauguin himself.

Fervent belief in "a consoling art for distressed hearts" became his refuge and nourishment: an art rooted in nature, but saturated with every shade of vision. By 1888, amid the blazing colours of Provence, he knew that he must surpass "the reflection of reality in a mirror" to mix a "resplendent" palette that matched the rainbow glory of his inner eye. Dejection and mania (possibly of epileptic origin) hardly ever impede the flow and the fire of his prose. Even in the month of his death, he assures Theo that "I still love art and life very much".

When he reads George Eliot, Vincent thrills to see "the soul at work". Follow these letters consecutively, or just dip in at random, and you will find a spiritual self-portrait of overwhelming radiance and depth.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments