Upstairs at the Party by Linda Grant, book review: Tale of doomed campus romance has more patchouli than plot

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

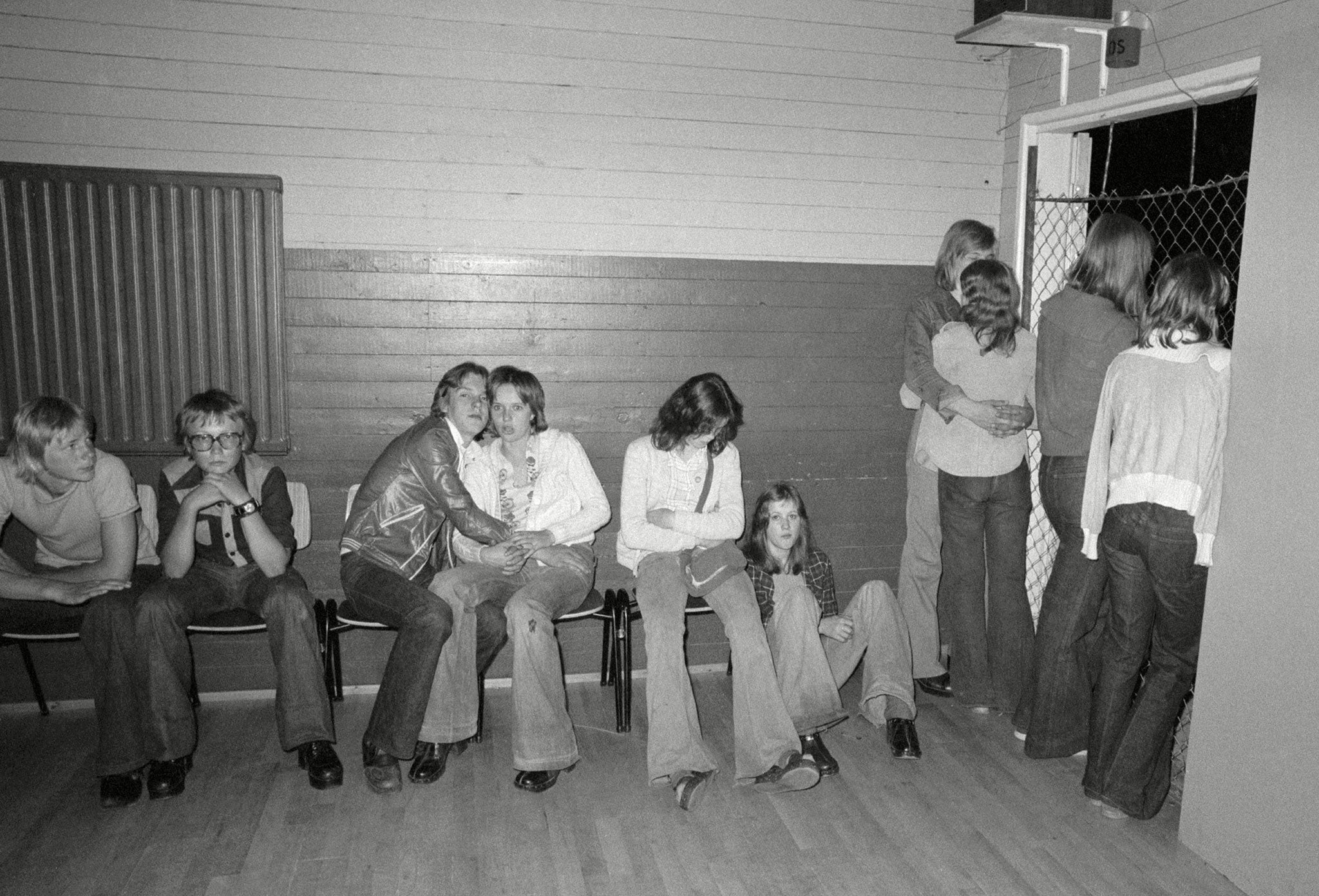

Your support makes all the difference.Linda Grant's previous novel We Had it So Good followed a group of friends from their student years at Oxford in the 1960s to the present day, a structure she returns to in Upstairs at the Party, though this time her characters meet in the "playpen" of a new 1970s university (never explicitly named as, but understood to be York, the author's own alma mater). It is a place bearing "no patina of age or fame. It was built of concrete, not Cotswold stone": a blank slate, like its students.

Too little of the narrative is actually set during the characters' university years for it to be strictly described as a campus novel, but the events of this period determine the direction of the narrative beyond the institution. At the core of the story lies the fate of a girl known as Evie, one half of the tantalisingly androgynous, gender-bending "silvery couple" Evie/Stevie whom everyone, but especially Adele, Grant's narrator, is captivated by. The mysterious Evie resembles the novel itself; at first glance an alluring enigma, but strip away the shiny exterior and there's a confusing absence of identity underneath. Grant's vision is clearly that of a Brideshead for a different generation – Adele's immature infatuation with Evie (she's possessed by a pulsing desire to kiss the nape of the girl's newly shorn neck) eventually develops into a full-blown but ill-fated affair with Evie's brother George, for example – but it lacks the sincere sense of loss that haunts Waugh's classic.

Which isn't to accuse Grant's novel of being frivolous; indeed one might describe it as too earnest. It's bleak in every way possible, from the wet and windswept campus with its austere breezeblock structures, to the harshness with which Grant takes her protagonists to task for the short-sightedness of their youthful ideals and beliefs: "We were only teenagers, we hardly knew if the egg we had cracked out of still held parts of its shell in our eyes and hair."

That said, the book comes alive in the description of the university years, and I couldn't help but wish she'd lingered in these hallowed, albeit pre-fab, halls a little longer. Once we leave them behind the narrative flounders. Evie's story is rambling and Adele's pursuit of it a matter of unconvincingly tying up loose ends.

The book opens with a note from the author explaining that although her characters and events are fictional, Upstairs at the Party is "inspired by a particular time in [her] own life", a sentiment immediately reinforced by Adele's opening lines: "If you go back and look at your life, there are certain scenes, acts, or maybe just incidents, on which everything that follows seems to depend. If only you could narrate them, then you might be understood." Adele might be trying to make sense of her past, but Grant seems mired in hers, and this is the overarching problem of the novel; fundamentally it feels more like an exercise in nostalgia than a cohesive piece of fiction. Grant, a previous Orange Prize winner, is usually so in command of her narrative; this one feels imposed after the fact, awkward and unyielding.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments