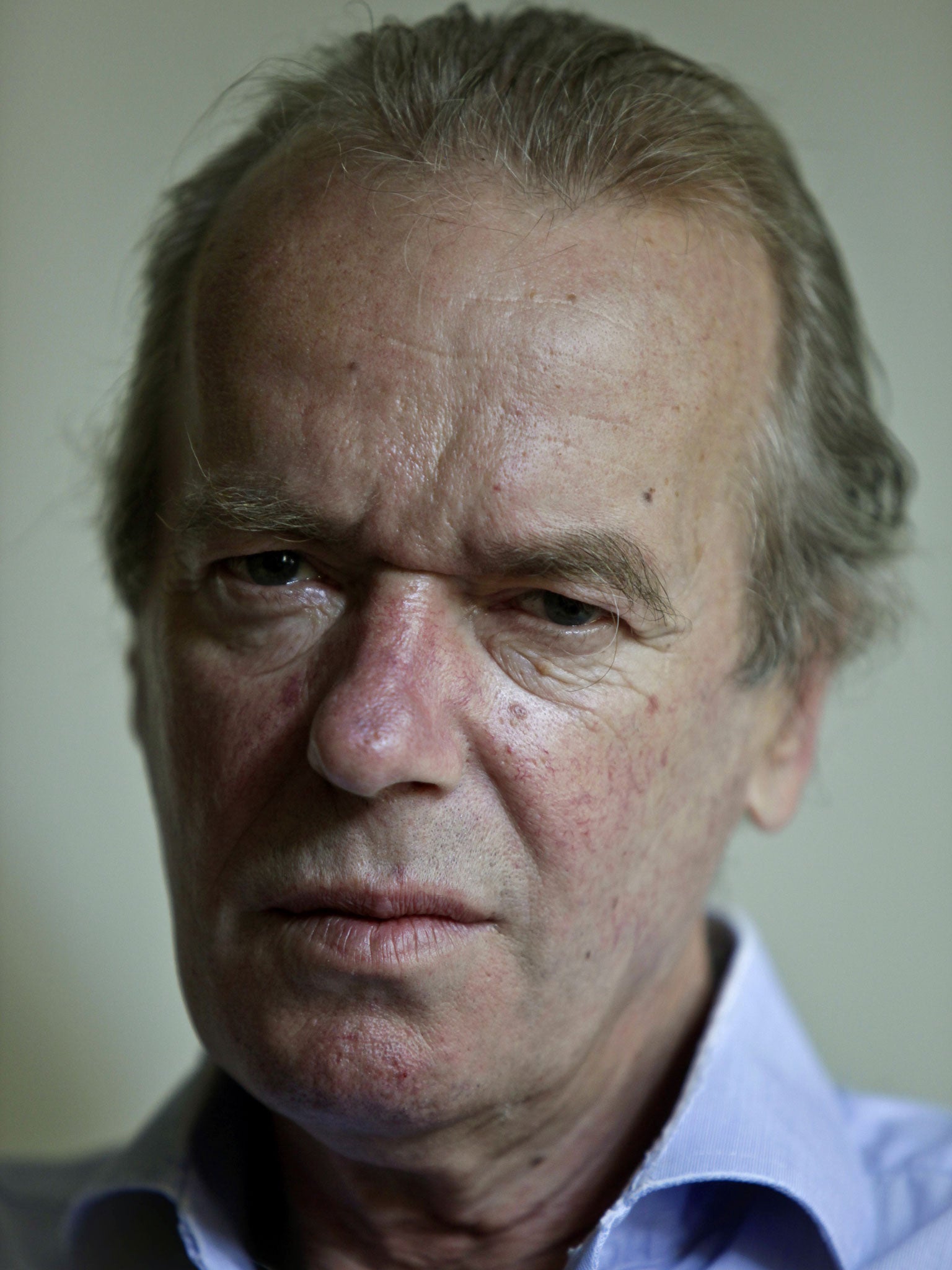

The Zone of Interest by Martin Amis – review by James Runcie

Here’s another holocaust novel. What’s more it’s another holocaust novel by Martin Amis. More than twenty years after the backwards narrative of Time’s Arrow (shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1991) comes The Zone of Interest. And so the reader’s first question must surely be: “Why?” Why tackle this subject again when you’ve done it before and we’ve already got the work of Primo Levi, Elie Wiesel, Irène Némirovsky Art Spiegelman, Anne Frank, Bernhard Schlink , Tadeusz Borowski, Jerzy Kosiński, Viktor E. Frankl and W.G.Sebald, to name but ten? Most writers are fearful of treading on this massacred ground; to go over it once more seems an act of folly. Clements Olin, the protagonist of Peter Matthiessen’s last novel, In Paradise, published earlier this year, “tends to agree with the many who have stated that fresh insight into the horror of the camps is inconceivable, and efforts at interpretation by anyone lacking direct personal experience an impertinence, out of the question.”

On the other hand, the German sociologist Theodor W. Adorno famously believed that the subject was unavoidable, and that to write about anything else was to persist in the perpetuation of the kind of self-satisfied contemplation and idle chatter of a barbaric culture that produced the holocaust in the first place. (“To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.”) W.G. Sebald once considered that no serious person ever thinks about anything else and, in answer to the question “Why”, one might quote Primo Levi’s desperate thirst after arriving in Auschwitz in February 1944:

“…I eyed a fine icicle outside the window, within hand’s reach. I opened the window and broke off the icicle but at once a large heavy guard prowling outside brutally snatched it away from me. ‘Warum?’ I asked him in my poor German. “Hier is kein warum,’ (there is no why here), he replied, pushing me inside with a shove.”

In a footnote at the end of the novel, Martin Amis cautiously explains the appeal of the subject matter, “that part of the exceptionalism of the Third Reich lies in its unyieldingness, the electric severity with which it repels our contact and our grip.” It is, perhaps, unsurprising that he should return. There are very few “normal” people in Martin Amis novels; they already inhabit a hyper-reality that perhaps finds its ultimate culmination in a concentration camp. The Zone of Interest is the mirror put up in a chamber of evil that reveals the horror of who we really are.

First up is Golo Thomsen, the nephew of Martin Boorman (compare and contrast with the protagonist of Time’s Arrow who has a thinly disguised Josef Mengele as “Uncle” Pepi). Golo is in his early thirties, an appropriately sexed up Nazi; “a tremendous scragger of the womenfolk” with, if you must know an “extensile penis, classically compact in repose (with pronounced prepuce)’”. He has fallen for the Kommandant’s gorgeously Aryan and unavailable wife Hannah Doll. (Amis seldom aspires to subtlety when naming his characters: John Self in Money, Terry Service in Success, Guy Clinch and Keith Talent in London Fields, Clint Smoker in Yellow Dog, the eponymous Lionel Asbo and of course the welcoming death figure Tod Friendly in Time’s Arrow.)

Hannah Doll is first described as “tall, broad, and full, and yet light of foot, in a crenallated white ankle-length dress” as if she is the subject of an impressionist painting, all haze and glade, but she is, of course, walking into Auschwitz.

Golo’s early appreciation of her charms is unlikely to appeal to feminists: “ …as I watched Hannah curve her body forward, with her tensed rump and one mighty leg thrown up and out behind her for balance, I said to myself: This would be a big fuck. A big fuck: that was what I said to myself.”

Amis’s use of italics here, as well as repetition, to make the point is a consistent tic. Here, for example, is Hannah’s husband, the Kommandant, explaining that if she has anything to do with Golo then he wants her dead.

“’Walpurgisnacht, nicht? Walpurgisnacht. Nicht? Nicht? Yech? Nicht? Yech? Nicht. Walpurgisnacht….Sonder, the only way you can keep your wife alive’, he said, ‘ ‘is by killing mine. Klar?’" One assumes that it is.

But any chance of adulterous consummation is prevented by a setting in which there is no privacy (Hannah is watched even when she is on the toilet) and the putative lovers are doomed to separation in a contemptuous world where the business of evil is made necessary and mundane. There is the usual checklist of genre references: The Protocols of Zion, the Jews as vermin, carbide gas, transport trucks, and instructions on how to burn human flesh. The result is a familiar and densely populated book in which it’s sometimes a bit of a hurdle to keep up with characters like “the hulking Horst Sklarz of the Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt, and the epicene Tristan Benzler of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt” (Pity the actor who has to read the Audiobook.)

Sexual compensation for violence lies at the centre of the novel and Hannah Doll’s husband is the stereotypical Nazi: drunk, brutal, cowardly, conniving, dangerous, sex-obsessed and, of course, misogynist (but since this is, perhaps a satire, then the use of stereotype is excusable, and the reader who thinks Kommandant Paul Doll no more than lazy caricature is surely missing the point. He is supposed to be a stereotype, thicko.)

The Kommandant’s attitude to women is not, therefore the product of an arrested schoolboy imagination but, of course, extremely amusing and sharply observed:

“Biggish Titten, such as those belonging to my wife, can be described as ‘beautiful’, smallish Titten, like Waltraut’s and Xonra’s, can be characterized as ‘pretty’ and Titten of the middlish persuasion can be designated as – what? ‘Prettiful’ Tittten? Such are Alisz’s Titten. ‘Prettiful.’ And her Brustwarten are excitingly dark.’”

There is a famous moment in Amis family history when Martin’s father hurled a copy of his son’s novel Money across the room, unable to continue. This, on page 132, was my Kingsley Amis moment. It just doesn’t work and the structure of the novel, the revelation of information, and the quality of focus is almost distractingly random. Perhaps that is the point too; there is no explanation for, in Hannah Arendt’s famous phrase “the banality of evil” in which a highly educated country goose-stepped into bestiality and disgrace. Things just happen and there is nothing anyone can do in a world that has lost energy for hope.

The litany of degeneracy does not make this an “enjoyable” read; but Amis is too good a writer to be boring; frustrating, yes, infuriating even, and then, round about page 270, when the war is over and we have reached “The Aftermath”, Amis does something even more irritating. He provides us with a moving and thoughtful ending that is so well achieved you want to shake both him and his editor, pin them against a wall and say “Why isn’t the whole book like this? Haven’t you heard of re-writing? This is the real deal, start with this, go back, cut out all the comedy sexism and make it better. Begin with the consequences; even go backwards all over again if you like, because this is what is interesting: How do you recover from evil?”

But they didn’t and they haven’t; so what we have is an overwhelmingly familiar re-iteration of barbarity with a powerful epilogue. It’s exasperating; but the final lack of sentimentally, guilt or apology, the understanding of shame and the inability of characters to “recover “ from the experience, make it a frustratingly memorable read.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments