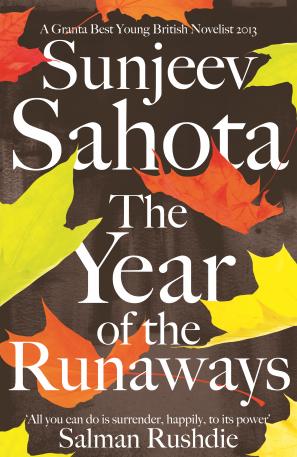

The Year of the Runaways, by Sunjeev Sahota - book review: New country, old problems

Picador - £9.99

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An ideal antidote to a year of reductive discussions of immigration, Sunjeev Sahota’s novel takes you deep into the lives of a group of Indian labourers thrown together in Sheffield. Deftly shifting in time and place, Sahota builds a portrait of the often painful circumstances that lead these men to abandon life in India for this cold, damp city, in the hope of starting afresh.

This is Sahota’s second novel. His first, Ours Are the Streets, was an acutely observed story of a young man’s shift from ordinary British Pakistani teenager to Muslim radical. The Year of the Runaways is no less accomplished in its lyrical prose and ability to immerse the reader in the experiences of a hidden community in Britain.

While a passing stranger might assume the circumstances of this group of Indian workers to be similar, Sahota brings to life the tensions and differences in background that transport India’s caste and class politics to a cramped, draughty house in Sheffield. All have found very different routes to England – from visa marriages, to enrolling as a “student”, and even selling an organ.

Tochi’s story offers a traumatic glimpse into life in a “Chamaar” family – one of the untouchable castes. After making a living as a rickshaw driver, in Britain Tochi faces the dizzying cliff-drop terror of using an escalator for the first time.

Randeep’s family were part of India’s growing wealthy middle class but a succession of events unravels his privilege. Teased in the house for being a prince, on his first night Randeep vomits up the “grey-yellow slurry” that passes as the men’s attempt at cooking curry.

These are not saints but humans. It is a testament to Sahota’s accomplished characterisation that he maintains sympathy with the men even after they commit crimes and take advantage of others.

Above all, this novel captures the growing realisation for new arrivals in Britain that life here can be just as hard – if not harder – than the one they left behind. Gurpreet, who has turned bitter after 11 years of toil and blind hope, sums up the jealousy and struggle that define the experience of these Indian exiles: “This life. It makes everything a competition. A fight. For work, for money. There’s no peace. Ever. Just fighting for the next job. Fight fight fight.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments