The Witches: Salem 1692. A history by Stacy Schiff, book review

Mass hysteria surrounding the notorious witch-trials at Salem is vividly re-created but the question of 'why' still lingers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

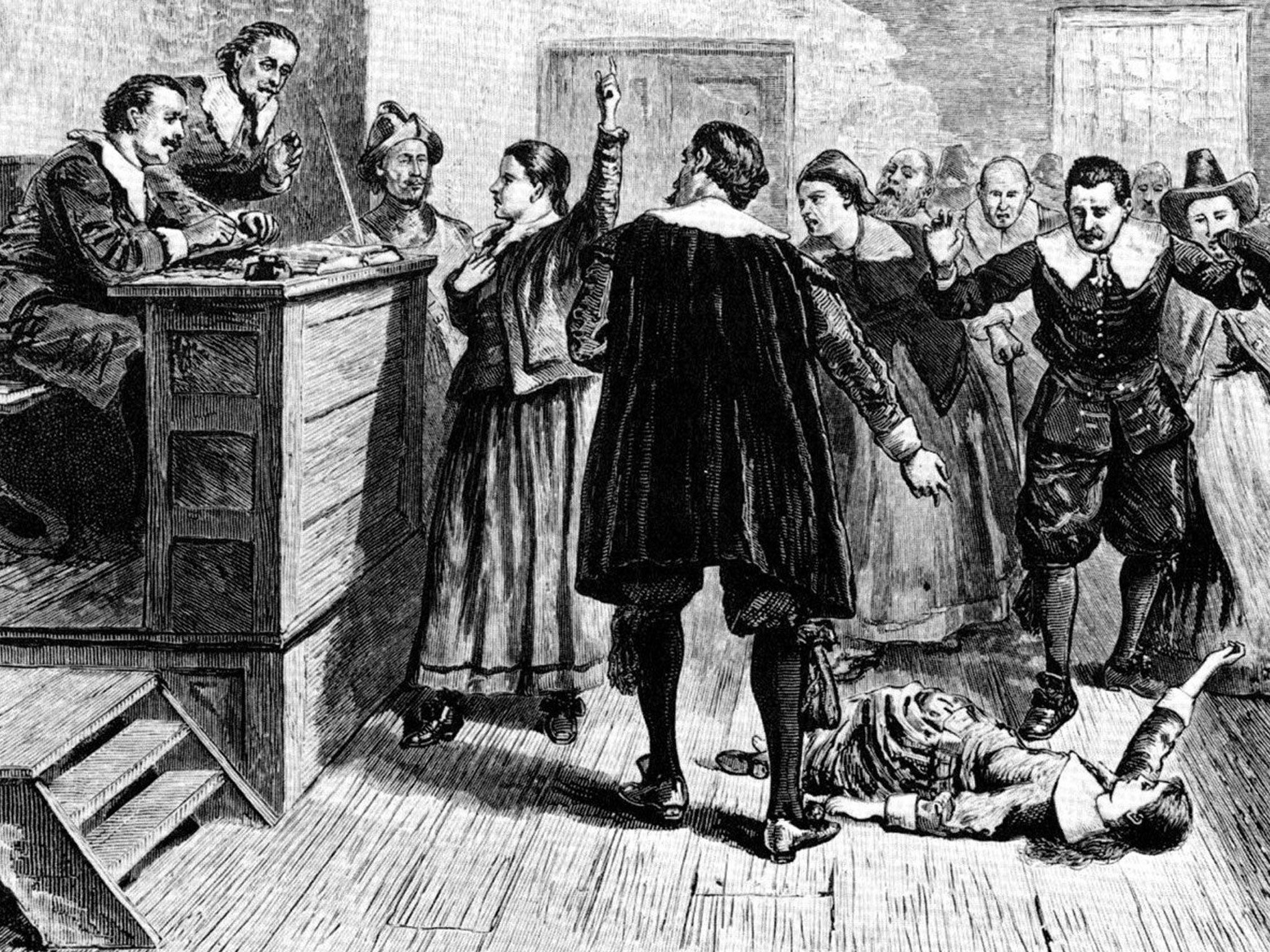

Your support makes all the difference.Arthur Miller described it as the "coming madness" in the overture of his 1953 play, The Crucible, which dramatised the moment in late-17th-century America when paranoia intersected with persecution to cause the perfect storm in the small town of Salem. Where, amid a God-fearing colonial community in Massachusetts, 20 men, women, children – and two dogs – were sentenced to death for witchcraft. The eldest was almost 80, the youngest, five. Some issued last pleas of innocence before being tripped off the scaffold. Between 144 and 185 witches were named in 25 villages and towns. Spectral visions of women flying through the air, or turning into cats and birds, were used as evidence. Girls, believed to be "bewitched" victims, provided a ghastly sideshow of fits and contortions to the gallery to corroborate the workings of sorcery.

Whether this was madness or mass hysteria, it was short-lived; a feverish delirium arriving in February 1692 and abating in May 1693. It is not the duration nor the death toll that makes this historical moment such a dark one, but the question of why a small, insular community of New Englanders ended up turning on one another with such fear and ferocity. Schiff provides reasons, though none particularly new: the alien threat lurking in the "wilderness" (Miller wrote of the fear of "Indian tribes marauding from time to time"); the Puritan's New World piety that inspired moral surveillance; the settling of old scores among neighbours who began informing on each other (Miller, again, wrote of "long held hatreds of neighbours [that] could now be openly expressed...").

The storm began when two girls, Betty and Abigail (the daughter and niece of Reverend Samuel Parris respectively) began having fits. Their stories of being bitten and tortured by spectres were taken as court evidence by ministers and prosecutors (few of whom were formally trained in the law); a special court was set up and it brought on the domino effect of more bewitched girls, more accused women (and a few men), and more defendants strong-armed into confessing to witchcraft in hope of escaping a death sentence.

The freshness that Schiff brings to these cases is in the colour and detail of the courtroom, the dungeon-like prison in Boston where the accused waited trial, and the gallows too. She points out that "no trace of a single session of the witchcraft court survives". The court reporting that remains is woefully inaccurate, with judgements being made and written into proceedings, the defendants' words mangled or omitted. So Schiff's is a feat of historical excavation and also of colourful reconstruction of the defendants, the husbands (never wives) who informed on them, the prosecutors and their grudges and the few rare folk who evaded the hangman's noose. We are given these people's family contexts, their appearances and court dialogue is vividly captured. Much of it is moving: the story of the six-year-old who confessed to being a witch; the case of pious Martha Corey who questioned the mental health of the "bewitched" girls on whose ravings she was sent to hang; the deviant outlier women like Sarah Osborne, Bridget Bishop and Sarah Good, the latter of whom was a semi-itinerant beggar who "constituted something of a local menace" and who seemed like pests to their neighbours sooner than broomstick demons. There was no way out for the accused: if they were church-goers, the court was reminded that witches had long infiltrated congregations; if they accused the "bewitched" girls of possession, they were demonic to think such a thing; once they got to court, their fate was met by these catch-22s.

Where there is ample colour, the triggers as to exactly why the witch-hunt began, and exactly why it stopped, remain misty. The final chapters are more analytical, and the most interesting as a result, when individual motives are examined – those of the men who dominated the trial, the bewitched girls whose fits fed it – most of the latter were fatherless and Schiff wonders whether their fits brought them the attention they badly craved. She tells us what came of the prosecutors, the claims of incompetence ("the ground shifted… the witches gradually became martyrs") and what happened to the bewitched girls as adults – some turned to prostitution, some married and some simply disappeared from historical record.

A discussion on "hysteria" in relation to the bewitched girls is all too brief, perhaps because of the lack of historical evidence. Schiff mentions the work of Jean-Martin Charcot, the neurologist who worked with hysterics in 19th-century Paris, and conjectures that these girls might have suffered from a similar malady. She makes a feminist case for these girls who "made themselves heard". This is disputable if, at the same time, she tells us that they were manipulated; confessions from some of the girls in adult life told of being groomed by prosecutors, and fed their words. Given more material, they would make a riveting book in its own right. Much has been written on the historical misogyny behind witchcraft accusations. Maverick, sexually-assertive women had, long before Salem, been classed as "witches", which feminism puts down to patriarchy's fear of femaleness. Schiff touches on the gender paradoxes of the Salem cases. On the one hand, there was a sense of rounding up vagabond women who defied New England's strict gender conventions that forbid them even to shake a fist in public. On the other, it was not just women at society's bottom rung who were persecuted (though the wealthy did get special privileges). Rich women and also men such as the well-bred former minister, George Burroughs, were not saved. He was, in fact, seen as the ringleader, his name barely uttered for fear of invoking the devil, like Salem's own Voltemort.

There is, in Schiff's final argument, the idea that Salem left a taint on national character. A certain "paranoid style" persists in American politics – "that apocalyptic, absolutist strain still bleeds into our thinking", she writes. There is perhaps a danger in extrapolating thus from one appalling act of historical delusion – where would that leave post-Holocaust Germany's national character? The more enduring lesson here is that the fear of terror can unleash its own terror, though frustratingly in the case of this book, one is still left wondering why.

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £20. Order at the discounted price of £17 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments