Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1980, Gay Talese was contacted by an anonymous motel owner who claimed to have been spying on his guests for over a decade. At the time, Talese was finishing his best-selling study of sexual morality, Thy Neighbour’s Wife, but he was intrigued by this self-described man of “unlimited curiosity about people” so he travelled to Colorado to meet him.

Talese excels at subtle characterisation and, when they meet at Denver airport, he tells us that the motelier, whose name is Gerald Foos, insists on carrying his luggage. Talese compliments Foos’ “highly polished black Cadillac sedan” and Foos responds by listing his other cars. These details might sound trivial but they establish Foos as a man who’s a little too eager to impress, a smooth-talker with an edge of insecurity.

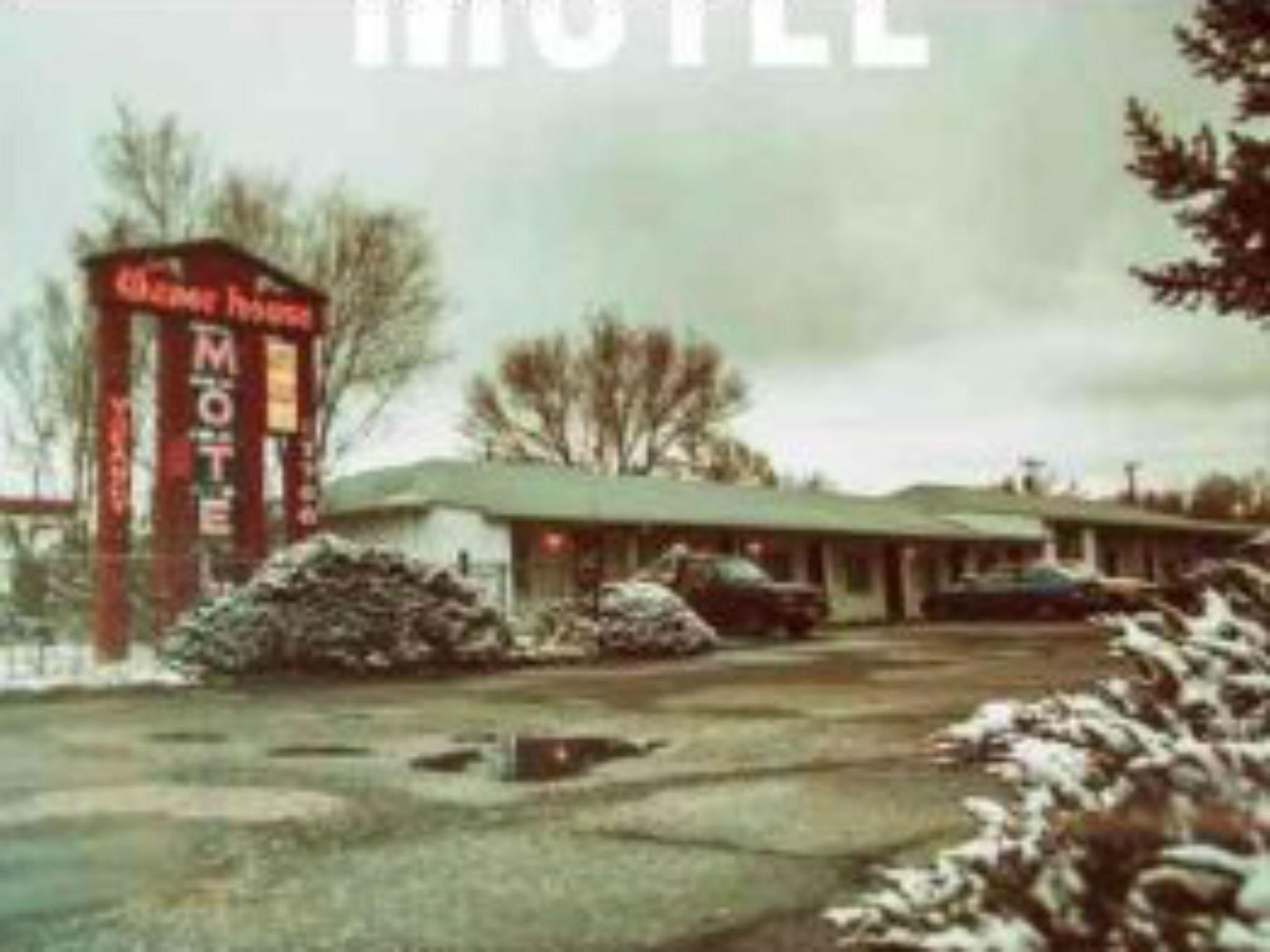

At the Manor House Motel, Talese meets Foos’ wife Donna, who knows about his spying, and hears about the couple’s two children who know nothing about it. Foos shows Talese the rooms where he’s installed custom-made vents which allow him to peer down from his “observation platform” in the attic. The pair watch a couple having sex but the game is almost up when Talese’s tie dangles through the vent. The book would have benefited from more of this kind of drama. Talese fails to persuade Foos to talk on the record but, for the next couple of decades, Foos sends him photocopies of his “Voyeur’s Diary”.

In 2013, Foos, who is, like Talese, in his 80s, finally agreed to go public with his story and Talese went to work on this book. A few weeks ago, however, Washington Post reporters claimed they’d discovered information that undermined Foos’ version of events. Initially, Talese said his book’s credibility was “down the toilet” but later retracted, deciding to stand by his, and Foos’, story. Talese admits Foos is a “master of deception” but, unfortunately, the prepublication controversy is the most interesting thing about The Voyeur’s Motel.

Foos’ diary entries are as banal as they are lurid. His descriptions of Vietnam War veterans’ private agonies capture an important aspect of America in the 1970s but, on the whole, the diary reads like an extended fantasy which raises doubts about its veracity and the value of Talese’s book. Talese wonders: “Had I become complicit in this strange and distasteful project?” The question is particularly pertinent when he reads Foos’ account of witnessing a murder at the motel in 1977 and failing to intervene. But Talese merely dabbles in the self-scrutiny that could have given his book depth.

According to Talese, Foos sees himself not as a peeping tom but as “a pioneering researcher whose efforts were comparable to those of the renowned sexologists at the Kinsey Institute.” This is, obviously, laughable, not least because Foos’ main conclusion, from invading thousands of guests’ privacy, is that people behave differently in private to how they behave in public. It’s difficult to believe that anybody doesn’t know this already, so spare yourself the trouble of reading this seedy little book.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments