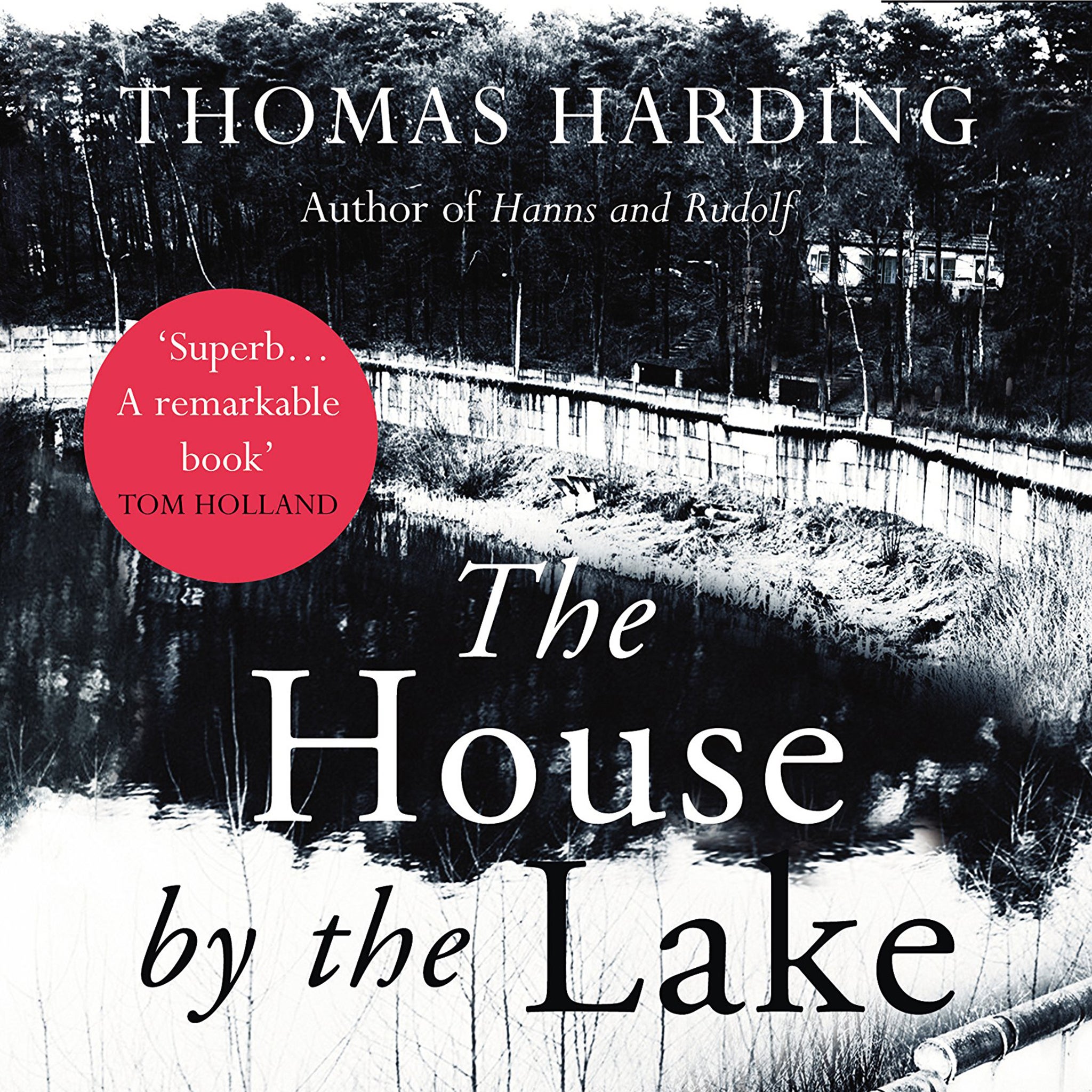

The House by the Lake: A Story of Germany by Thomas Harding, book review: A deft history of a cabin containing many secrets

It’s bold to call the tale of a wooden cabin 'a story of Germany', but Harding weaves the saga of the house’s many occupants so deftly into the wider drama of 20th-century German history that he pulls it off

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ripping yarns about the rise and fall of big houses – tales of titled owners whose crumbling piles tell a broader story about tectonic shifts in society – are big in the book world. The subject of this book at first seems too modest to serve any such purpose. This is a chalet not a chateau, and how many secrets can a cabin contain? Harding – whose research into what took place between these woody walls over decades is impressive – shows that the answer is: plenty.

It helps that the author has a personal stake. It was Harding’s great-grandpa, a Jewish doctor in Berlin, who built the cabin by a lake near Berlin in 1927 as a retreat for his growing family. The Alexanders were doing well, a Jewish family on the up in the deceptively easy-going Weimar Republic. Einstein came to dinner, that sort of thing.

For half-a-dozen summers the family swam and pottered by the lake. Then Hitler took power and Nazi paramilitaries started drilling in the nearby village of Gross Glienicke. The summers by the lake ended. The Alexanders were lucky in one sense. They got out. Harding’s great-aunt Bella married an Englishman in 1934 and moved to Britain. In 1936, the year of the Berlin Olympics, she persuaded her parents and Harding’s grandmother to do likewise. They lived. Still, like most German Jews, the Alexanders effectively had to give away their property, which explains why the slippery Will Meisel got hold of the lease for a pittance.

The cabin was the Meisel summer home now, but they had to flee in their turn. In 1945, the Russians conquered Berlin and the city was divided into occupation zones. Some of the summerhouses by the lake fell into the Western zone but the Alexanders’ old place, along with the village of Gross Glienicke, fell into the Soviet zone – by a few yards. The Berlin Wall, erected in 1962, was practically at the end of the garden.

With the property now nationalised in East Germany, the cabin became a proper home for the first time and two families moved in, one of whom, the Kuhnes, stayed for decades. The years rolled by and the Alexanders and the Meisels became a distant memory. Then, as suddenly as it went up, the wall came down. Westerners flooded into Gross Glienicke, some of them scaring the villagers with talk of repossessing their long-lost homes. Harding did not follow suit.

It’s bold to call the tale of a wooden cabin “a story of Germany”, but Harding weaves the saga of the house’s many occupants so deftly into the wider drama of 20th-century German history that he pulls it off.

Order for £18 (free p&p) from the Independent Bookshop: 08430 600 030

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments