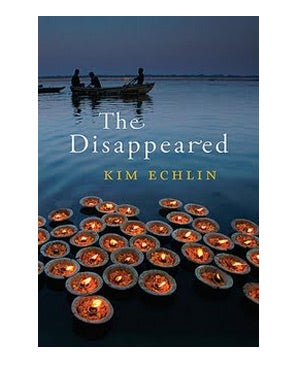

The Disappeared, By Kim Echlin

A love that pulses in the killing fields

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Despite everything written about Pol Pot's regime in Cambodia (1975-1979), it is still possible to be deeply shocked by stories of the two million who died in the killing fields, were tortured or simply disappeared. The Canadian novelist Kim Echlin has written a love story that exposes in terrible detail the consequences for generations of Cambodians of living through "Year Zero". As her protagonist, Anne Greves, asks, "why do some people live a comfortable life and others live one that is horror-filled?"

Answering that question becomes Anne's quest after she meets, in Montreal aged 16, a Cambodian refugee and musician named Serey. They fall deeply in love and seem bound together, since Serey is exiled from his family while Anne's life has been shaped by losing her mother. When Serey learns the Cambodian border has re-opened after the Vietnamese invasion, he leaves Montreal to search for his missing family. For a decade Anne hears nothing, learns to speak Khmer, and waits.

Convinced that Serey is still alive after seeing him on television, she leaves for Phnom Penh. Miraculously, they are reunited and their relationship seems to resume effortlessly. But Echlin is too talented a writer and far too committed to revealing the brutal truth of war to allow her lovers a happy ending.

The novel's lyrical prose spins out Anne's thoughts and responses to the brutality she encounters. The horror, however, is balanced by Anne and Serey's profound love; after their reunion, she remembers, "I opened myself to you as if I could be unzippered front and back... We became cannibals swallowing flesh and breathing prayers."

But at times the prose becomes overwrought and detracts from a deeper understanding of the Khmers' experience. It's almost a relief when Will, a gruff Canadian forensics expert, appears to help Anne in her search, muttering his hope "that our humanity might kick into a higher gear". This is an ambitious novel that almost, but not quite, reaches its goal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments