The Children Act by Ian McEwan, book review: Not as good as Atonement, but what modern novel is?

Though not itself perfect, his eighth novel embodied a high-water mark in modern (and Modernist) fiction

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

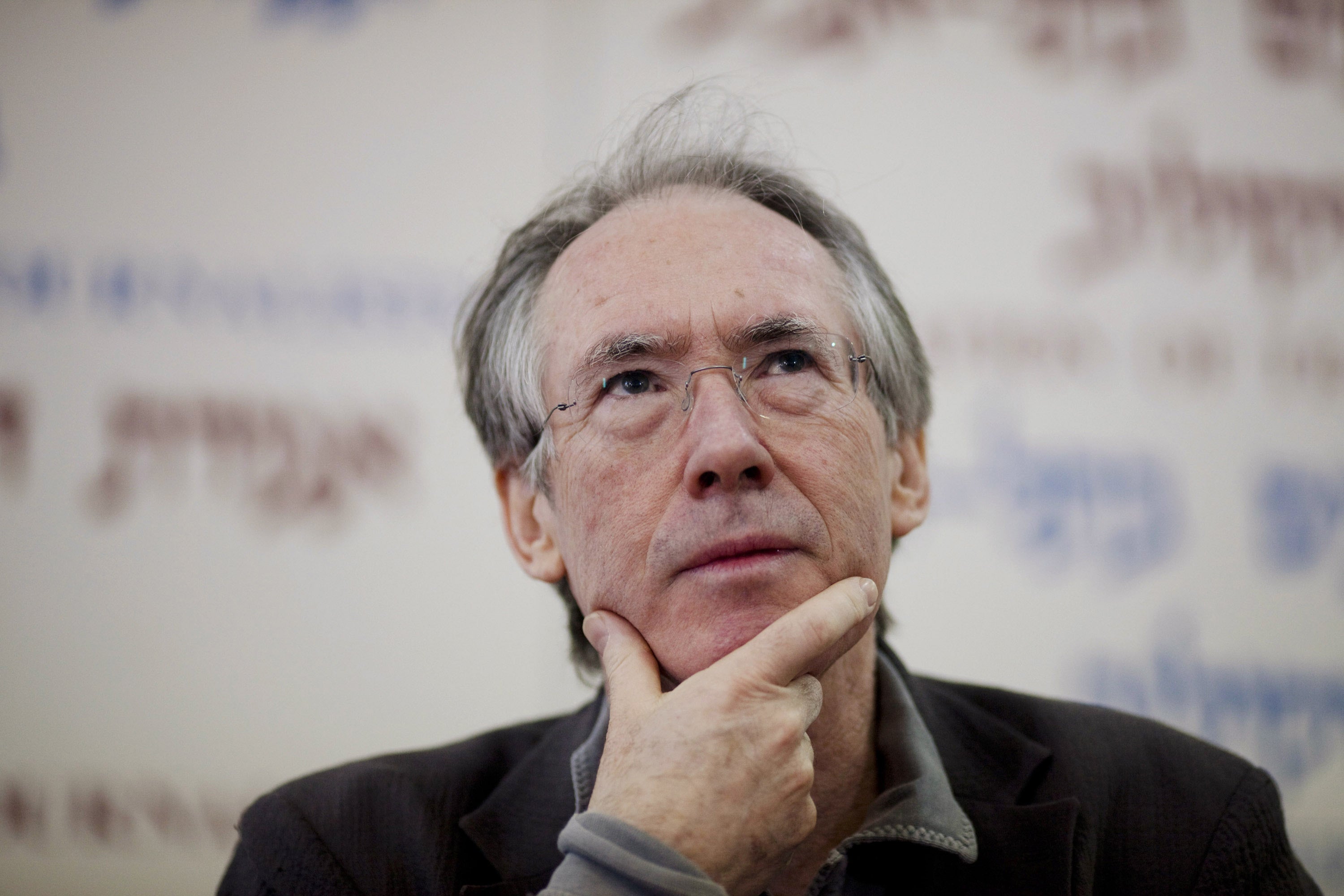

Your support makes all the difference.How is it possible, you may ask, for Ian McEwan to not make the Booker long-list?

The Children Act, his 13th novel, is very much in the same vein as Saturday in that it concerns the confluence of the life of a member of the professional elite – a judge rather than a surgeon, this time – with that of the less fortunate. This is a brave and enormously interesting subject, given the deepening gulf between rich and poor, not just in terms of income but of power.

McEwan’s heroine, Fiona Maye, is a childless High Court judge living in the refined enclaves of Gray’s Inn Road in London. Distinguished, admired and a gifted amateur pianist, her professional success at adjudicating exquisitely difficult cases in the Family Courts is under-cut by Jack, her husband of 30 years, telling her that the lack of sex in their marriage has driven him to want an affair with a younger woman. On the same day, she has to make a decision about whether to order a life-saving blood transfusion for a 17-year-old boy, Adam, who is a Jehovah’s Witness. Fiona decides that the only way she can tell whether the boy is mature enough to make his own decisions, is to visit him in hospital during the critical hours before his decline is too advanced to be arrested.

As in Saturday (and the dismal Amsterdam), McEwan’s approach to his chosen professional arena is immersive. Fiona’s gift for razor-sharp precis merges well with the novelist’s own – so much so that, at 213 pages, the novel is half the length it might have been. The effect of this gives the novel not just a prevailing sense of interiority, but a shut-down quality in which the messier textures of human intercourse we expect in realist fiction are not allowed to breathe – appropriate in that this is something that Adam will experience with leukaemia. Yet it is McEwan’s fidelity to particularising the general and generalising from the particular which makes him so absorbing, and even though the plot has a formulaic aspect which might have come straight from HBO’s The Good Wife, he does not disappoint, largely because his unostentatious, plate-glass prose gives us the illusion of looking into rather than at his character’s lives. Has Adam been brainwashed by his parents’ religion or does he, like many teenagers, have a Romantic conception of death? Kindly, subtle, scrupulous, Fiona’s secular intelligence must go into combat with superstition and ignorance before she can use her power as a judge.

The central scene, in which Fiona teaches Adam the words of Yeats’s poem “Down by the Salley Gardens” to the Irish air he has just taught himself to play on the violin is where the characters are allowed to expand, clashing and sparking off each other. It is beautifully done, not least because any reader obsessed by music will long ago have recognised a kindred spirit in McEwan. Here, both the poem and the music turn Adam from one course of action to another; yet art can’t save him. Only love can.

Fiona is beautifully drawn, so much so that one often has the sense of meeting one’s own thoughts and feelings. Frequently accused of failing to depict the opposite sex accurately (his preposterous notion that a woman might avert rape by reciting “Dover Beach” in Saturday has become a feminist joke) his heroine’s ambition, honesty and workload are here all treated with understanding and respect. However, the concept that a woman might genuinely feel fulfilled by being childless is not, and ultimately, this makes it underpowered and unoriginal. It is clear from the start that the “goals towards which a child might grow … having at the centre of one’s life one or a small number of significant relations defined above all by love” is something Fiona has, novelettishly, let slip. With his beauty, youth, energy and talent, Adam moves her because of this vacuum. Is he the son she never had, or the love of life she has let slip?

McEwan’s attentiveness to shades of meaning in his titles may make one note that The Children Act lacks the possessive apostrophe. There is a play on the world “act” (Fiona’s words have an impact on real lives) and the way individual children lack power, despite the stated intent of the Act to put a child’s welfare first.

In short: this novel is not as good as McEwan’s Atonement, but what modern novel is? Though not itself perfect, his eighth novel embodied a high-water mark in modern (and Modernist) fiction; The Children Act, with its sly allusions to many of the author’s own past works, seems inferior only when comparing this to his own oeuvre – and to his contemporaries’.

Amanda Craig’s latest novel, Hearts and Minds, is published by Abacus, £8.99.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments