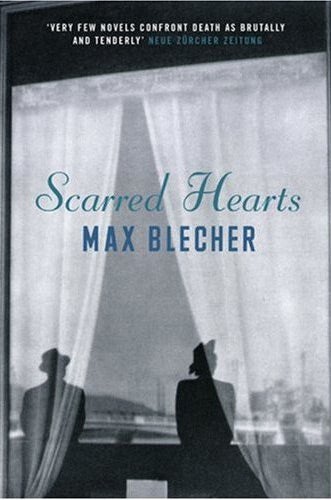

Scarred Hearts, By Max Blecher (trans Henry Howard)

A lost classic that is an uneven mix of Thomas Mann and Mills & Boon

In recent years, the work of Joseph Roth, Antal Szerb, Leonid Tsypkin and Stefan Zweig has been rediscovered, treating readers to some delightful "lost classics". Each of these minor Mitteleuropean writers has a unique voice to be treasured, despite the slightness of some of their work and the overindulgence of some critics. Max Blecher's Scarred Hearts comes to us packaged as just such a lost classic. It was his second and last novel (in 1937), and Paul Bailey's introduction tells us that Blecher's "elegant style" was compared to that of Kafka and Rilke. Bailey also calls the novel a "masterpiece".

Blecher was born in 1909, into a Jewish family in Romania. At 19, he contracted spinal tuberculosis and was hospitalised. Scarred Hearts centres on Emanuel, a Romanian student, who in the opening chapter is diagnosed with Pott's disease. His attentive father thinks that only a spell in the sanatorium at Berck-sur-Mer, in northern France, will cure his son: "All the patients here lead normal lives... They dress normally, they go about on the streets... only they do it all lying down."

On his first morning at the sanatorium, Emanuel is faced with a surreal vision of the dining room: "The patients lay on their stretcherbeds, two at a table. It might have resembled a banquet from antiquity... if the drained, pallid faces of the worst sufferers hadn't shattered any illusions." Unfortunately, descriptions of the strangeness of life at Berck, and the alienating effects of illness, are too often sacrificed to an uneven mix of Thomas Mann-lite, which nestles alongside the Mills & Boon emotings that describe Emanuel's relationship with Solange: "She was an animal every bit as splendid as his horse, which he adored more than anything."

Constantly, Blecher tells us what a "melancholy" world this is. Emanuel's love affair, and the tragicomic episodes featuring his fellow-patients are an attempt to show that life must go on, but Blecher doesn't ever fully face the implications of his own words: "When someone is, all of a sudden, removed from life and has the time and the necessary calm to ask himself a single, essential question regarding it – one single question – he is poisoned forever." Here is the existential heart of the book, but Blecher shows himself unwilling to tackle its consequences.

Instead, we get a weak pastiche of Mann's The Magic Mountain. Sadly, this is a lost classic that did not need to be found.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies