Run, Swim Throw, Cheat: The Science Behind Drugs In Sport, By Chris Cooper

A scientific review of genetic technology that can give tomorrow's athletes a helping hand

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Do you entertain a fancy that your child might be cut out to sprint for Britain? Or take on the marathon? It may be time to stump up £169 for a home-testing kit that will tell you if he or she has a mutation – or polymorphism – in the ACTN3 gene. That will decide whether or not it's track or road for your sporty offspring.

Of course, it's not as simple as that. Genes alone do not produce great athletes any more than they do great artists or great particle physicists. Home-testing your child's genetic make-up is perfectly legal, and will continue to be so. But what about gene-doping – actually manipulating those genes? Would that be legal? And why is it acceptable to ride a bike designed to leave your opponents behind, but wrong to take steroids, or even too much caffeine? Why is it OK to train at altitude but not take a drug to mimic the effect?

Sports doping is a complex and contentious issue, and the biochemist Chris Cooper, professor at the Centre for Sports and Exercise Science at Essex University, presents a vast array of technical detail. It's an overview rather than a polemic. Cooper is not even 100 per cent certain that sports doping is wrong: he quotes Julian Savulescu, editor of the Journal of Medical Ethics, who believes banning drugs in sport actually cheats the athletes by not allowing them to realise their potential. He also believes parents are morally obliged to utilise genetic technology to produce the best children possible.

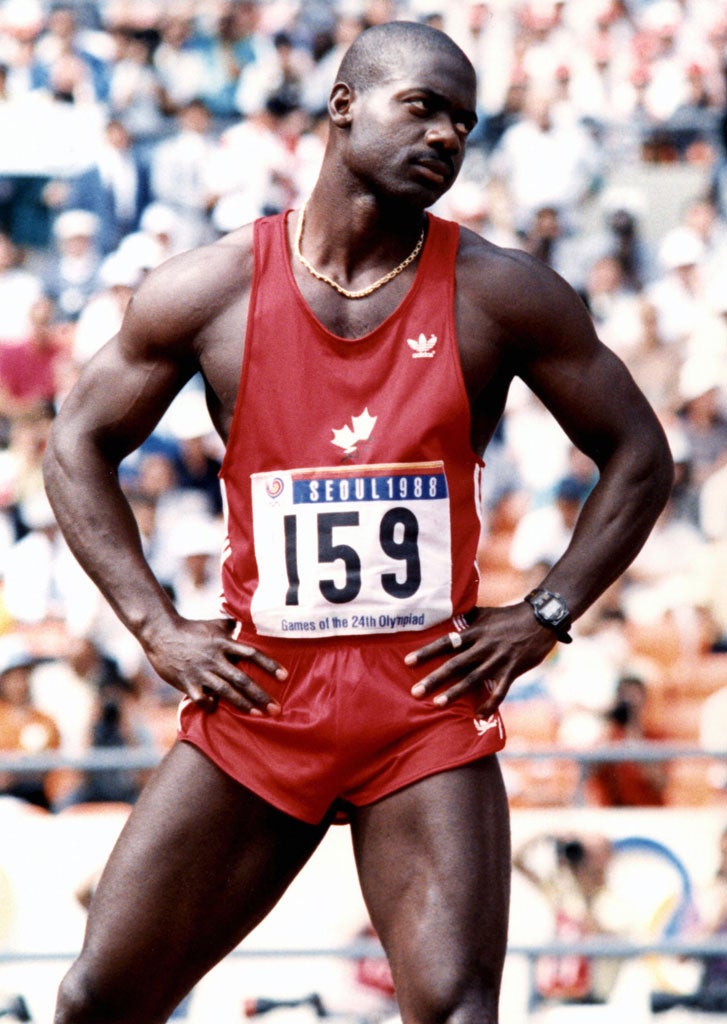

Cooper begins his account with the "dirtiest race in history", the men's Olympic 100 metres final in 1988, infamously "won" by Ben Johnson. Of the eight finalists, a staggering six would go on to be implicated in sports doping. But it is not just the able-bodied who are at it. He writes about the wheelchair racers who resort to "boosting" – tricking the insensate lower half of the body into sending stress messages back to the brain in order to increase heart rate and thereby improve performance. Methods include strapping up the legs too tightly, sitting on the scrotum – even breaking a bone.

There is a huge amount of scientific detail, and a few myths – like the supposed genetic superiority of East African runners – are trashed along the way. In fact, there is so much detail that, fascinating though it is, general sports fans without a scientific bent might find it a struggle.

The future for drug-testers, as you might imagine, is not bright. Biological passports – which set out an athlete's normal physical parameters, against which future readings can be checked – can help but the dopers, it seems, will generally keep their noses in front.

The most disturbing, depressing passage tells of the US geneticist who took a call from a high-school football coach. He wanted his entire team gene-doped. As Cooper concludes, there are no simple solutions.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments